What Past Global Warming Reveals About How Future Rainfall May Change

To understand how today’s rising temperatures could reshape rainfall patterns in the future, climate scientists often look far back in time. One period that offers especially valuable clues is the early Paleogene, which began about 66 million years ago, shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs. During this era, Earth experienced extreme global warmth, with atmospheric carbon dioxide levels estimated to be two to four times higher than today. A new study suggests that this ancient warming did not simply make wet regions wetter and dry regions drier. Instead, it fundamentally altered how and when rain fell, with important lessons for the modern world.

The research, led by scientists from the University of Utah and the Colorado School of Mines, focuses on how rainfall behaved under these hot, greenhouse-like conditions. Their findings were published in Nature Geoscience in a paper titled “More intermittent mid-latitude precipitation accompanied extreme early Palaeogene warmth.” The study draws on both geological evidence and climate modeling to reconstruct precipitation patterns from tens of millions of years ago.

Looking to the Paleogene for Climate Clues

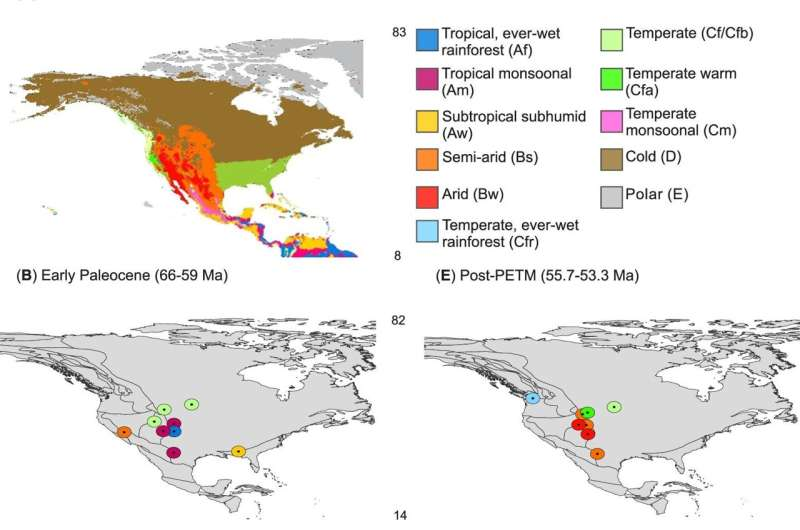

The Paleogene Period spans from 66 to about 23 million years ago, but this study zeroes in on its warmest stretch, roughly 66 to 48 million years ago. This interval includes the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a well-known episode of rapid and intense warming. During the PETM, global temperatures were about 18 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than pre-industrial conditions, making it one of the hottest times in Earth’s history.

Some scientists view this period as a possible worst-case analogue for future climate change. While today’s warming is happening much faster, the Paleogene shows what Earth’s climate system can look like when greenhouse gas levels remain very high for long periods.

Challenging a Common Climate Assumption

A widely held idea in climate science is that as the planet warms, wet regions tend to get wetter, while dry regions become drier. This assumption is based on solid physical reasoning: warmer air can hold more moisture, which can intensify rainfall where storms already occur. However, the new study suggests that this picture is too simplistic, especially when warming reaches extreme levels.

The researchers found that even mid-latitude regions, which today include large parts of North America, Europe, and Asia, often became drier overall during the early Paleogene. Importantly, this drying did not always mean less total rainfall across the year. Instead, it reflected changes in rainfall timing and regularity.

Rainfall Became Less Predictable

Rather than focusing solely on how much rain fell annually, the research team examined when rain fell and how often. Their results show that under extreme warming, rainfall became far more intermittent. Long dry spells were frequently interrupted by short periods of very intense rainfall.

In many regions, this pattern resembled a strongly monsoonal climate, even outside the tropics. Such conditions can be difficult for ecosystems to adapt to. Extended dry periods stress plants and soils, while sudden downpours can cause flooding and erosion rather than providing steady moisture for vegetation.

The study concludes that during the early Paleogene, polar regions were surprisingly wet, in some cases experiencing monsoon-like rainfall. In contrast, continental interiors and many mid-latitude areas faced drier conditions because rain arrived less reliably, even if annual totals were not drastically reduced.

How Scientists Reconstructed Ancient Rainfall

Since no one can measure rainfall from millions of years ago directly, the researchers relied on climate proxies, which are indirect indicators preserved in the geological record. Geologists from the Colorado School of Mines analyzed several types of proxy data.

One key source of information came from plant fossils. The shape and size of fossilized leaves can reveal a great deal about ancient climates. By comparing fossil leaves to modern plants with similar characteristics, scientists can infer past temperature and humidity conditions.

Another important proxy was ancient soil chemistry. Soils form differently depending on how much rain falls and how consistently it arrives. Certain chemical signatures can point to prolonged dry periods or episodes of intense precipitation.

The team also examined river deposits and landscape features. Intermittent heavy rainfall followed by drought shapes river channels differently than steady, gentle rainfall. Powerful floods can carve deep channels and transport large amounts of sediment, leaving behind clear geological evidence.

Combining Proxies With Climate Models

While proxy data provide crucial clues, they also come with uncertainties. To strengthen their conclusions, the researchers combined geological evidence with climate modeling, led by atmospheric scientists at the University of Utah. These models helped test whether the reconstructed rainfall patterns were physically plausible under Paleogene climate conditions.

One striking result was that modern climate models may underestimate how irregular rainfall can become under extreme warming. The models tended to smooth out precipitation patterns, while the proxy data suggested much greater variability. This mismatch highlights the importance of using ancient climates to test and improve current climate simulations.

Changes That Lasted Millions of Years

Another notable finding is that these altered rainfall patterns were not limited to brief warming spikes like the PETM. Evidence suggests that shorter wet seasons and longer dry intervals began millions of years before the PETM and continued long afterward. This implies that once Earth’s climate system crosses certain thresholds, rainfall behavior can shift in lasting and unexpected ways.

In other words, changes in precipitation timing and reliability may persist even if temperatures stabilize, adding another layer of complexity to future climate projections.

Why Rainfall Timing Matters More Than Averages

For both ecosystems and human societies, when rain falls can be just as important as how much falls. Long dry spells can damage crops, reduce water supplies, and increase wildfire risk. Intense downpours, meanwhile, can overwhelm drainage systems, cause floods, and erode soils without adequately replenishing groundwater.

The Paleogene record shows that extreme warming can produce climates where rainfall is less dependable, making water management far more challenging. This insight has major implications for agriculture, infrastructure planning, and disaster preparedness in a warming world.

Extra Context: Why Paleoclimate Studies Are So Valuable

Studying ancient climates like the Paleogene helps scientists understand the full range of Earth’s climate behavior. Instrumental records only cover the past century or two, which is a very narrow window compared to Earth’s long history. Paleoclimate research reveals how the climate system responds under conditions far outside modern experience.

These studies also highlight that climate change is not just about temperature. Hydrological changes, including rainfall variability, drought frequency, and flood intensity, often have more immediate impacts on ecosystems and societies. By learning how these systems behaved during past greenhouse periods, scientists can better anticipate future risks.

What This Means for the Future

The key takeaway from this research is that future climate change may not simply rearrange where rain falls. It could dramatically alter the rhythm of rainfall itself, leading to longer dry periods punctuated by heavier storms. As global temperatures continue to rise, understanding and preparing for these shifts will be essential.

Rather than focusing only on yearly rainfall averages, planners and policymakers may need to pay closer attention to seasonality, variability, and extremes. The ancient past suggests that these factors could define the real-world consequences of a much warmer planet.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-025-01870-6