El Niño and La Niña Are Synchronizing Global Droughts and Floods, Scientists Find

Water-related extremes like droughts and floods shape daily life across the planet. They influence drinking water supplies, agriculture, ecosystems, food prices, migration, and even political stability. A new scientific study now shows that these extremes are not happening in isolation. Instead, they are increasingly moving in sync across the globe, driven largely by two well-known climate patterns: El Niño and La Niña.

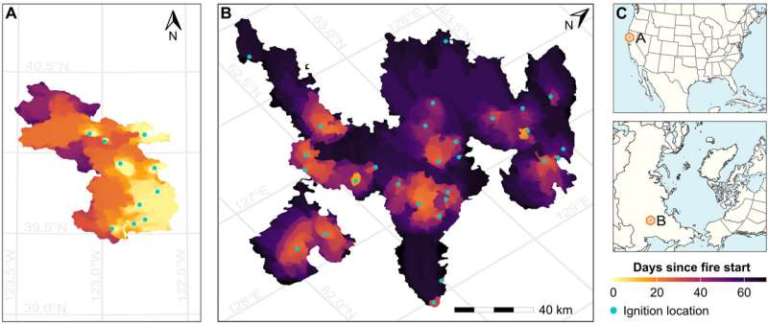

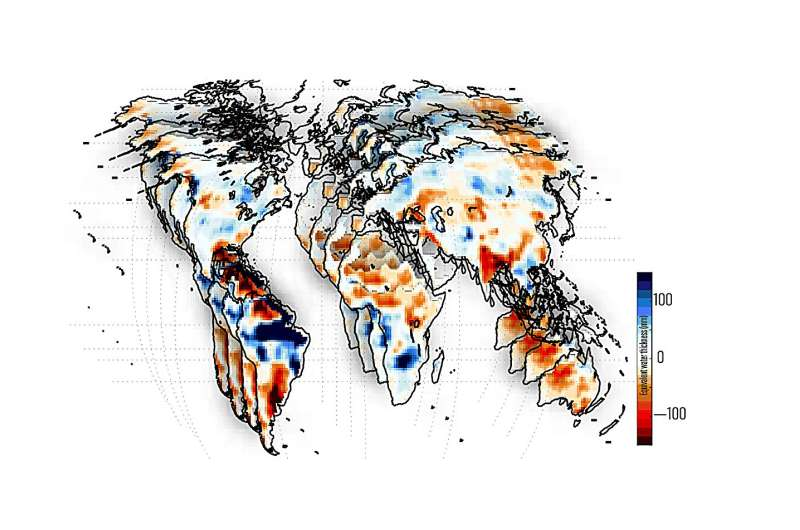

Researchers from The University of Texas at Austin have analyzed more than two decades of satellite data and discovered that the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, has been the dominant global driver of extreme wet and dry conditions since the early 2000s. Even more striking, ENSO appears to be synchronizing water extremes across continents, meaning distant regions can experience droughts or floods at the same time.

Tracking Earth’s Water From Space

At the center of this research is a powerful but less familiar climate metric called total water storage. Unlike traditional measures that focus only on rainfall or river flow, total water storage captures all water in a region at once. This includes surface water in rivers and lakes, snow and ice, soil moisture, and groundwater stored deep underground.

To measure this, scientists relied on data from NASA’s GRACE and GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO) satellites, which have been orbiting Earth since 2002. These satellites do not observe water directly. Instead, they detect tiny changes in Earth’s gravity caused by shifts in water mass. When water accumulates or disappears in a region, gravity changes slightly, and GRACE can detect that signal.

Using this method, researchers estimated water storage changes across areas roughly 300 to 400 kilometers wide, comparable to the size of the U.S. state of Indiana. The dataset spans 2002 to 2024, making it one of the most comprehensive global records of water storage ever assembled.

How the Study Defined Extreme Conditions

Rather than counting individual droughts or floods, the researchers took a different approach. Extremes, by definition, are rare, which makes long-term analysis difficult. To overcome this, the team focused on spatial connections between extremes.

They defined:

- Wet extremes as periods when total water storage exceeded the 90th percentile for a given region

- Dry extremes as periods when total water storage fell below the 10th percentile

This approach allowed scientists to examine how extreme wet and dry conditions appear together across different parts of the world and how those patterns shift over time.

ENSO as a Global Synchronizing Force

The analysis revealed that ENSO has been the strongest driver of global water storage extremes over the past two decades. During abnormal ENSO phases, regions thousands of kilometers apart were often pushed into similar wet or dry states simultaneously.

Importantly, ENSO does not affect all regions in the same way. In some parts of the world, El Niño is linked to dry extremes, while in others La Niña plays that role. The pattern reverses for wet extremes. What matters most is that ENSO acts as a global organizing force, aligning water extremes across continents.

Several real-world examples stand out:

- Mid-2000s South Africa experienced severe dry extremes during an El Niño phase

- The Amazon basin faced intense drought during the 2015–2016 pan-tropical El Niño

- During 2010–2011, a strong La Niña coincided with extreme wet conditions in Australia, southeast Brazil, and South Africa

- From 2019 to 2022, La Niña contributed to widespread floods and droughts across multiple continents at the same time

These events, once viewed as mostly regional disasters, now appear to be interconnected expressions of the same climate rhythm.

A Global Shift After 2011

One of the most important findings of the study is a global transition in water extremes around 2011–2012. Before this period, wet extremes dominated globally. After 2012, dry extremes became more frequent and widespread.

Researchers attribute this shift to a decadal-scale climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean that modifies how ENSO influences global climate. While the GRACE record is relatively short in climate terms, the consistency of this shift suggests that large-scale ocean-atmosphere interactions can tilt the planet toward prolonged dryness or wetness for years at a time.

Filling the Data Gaps

The GRACE satellite record includes an 11-month gap between 2017 and 2018, when the original mission ended and GRACE-FO had not yet begun. To address this, the research team used probabilistic models based on spatial patterns observed during periods with satellite coverage. This allowed them to reconstruct water storage extremes during missing intervals without breaking the global analysis.

Even with only 22 years of data, the study demonstrates how tightly connected Earth’s climate and water systems are, and how much insight can be gained from satellite-based observations.

Why This Matters Beyond Science

The synchronization of droughts and floods has major humanitarian and economic implications. When multiple food-producing regions experience drought at the same time, global food supplies tighten. When floods hit several major river basins simultaneously, infrastructure damage and disaster response systems are strained.

Understanding where regions are simultaneously wet or dry can help governments, aid organizations, and global markets prepare for cascading impacts on water availability, agriculture, food trade, and economic stability. The findings also shift the narrative away from simply “running out of water” and toward the challenge of managing extremes.

Understanding ENSO and Its Global Reach

ENSO originates in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, where changes in sea surface temperatures and atmospheric pressure alter wind patterns and ocean circulation. El Niño typically involves warmer-than-average Pacific waters, while La Niña is marked by cooler conditions. These changes ripple through the atmosphere, reshaping rainfall and temperature patterns worldwide.

This study reinforces the idea that ENSO is not just a Pacific phenomenon. It is a planetary-scale driver that links distant regions through shared climate dynamics.

The Growing Role of Satellite Hydrology

The research also highlights the growing importance of satellite hydrology in climate science. Ground-based measurements of groundwater and soil moisture are sparse in many regions. GRACE and GRACE-FO provide a consistent, global perspective, making it possible to detect patterns that would otherwise remain invisible.

As climate variability intensifies, such satellite missions are becoming essential tools for understanding and preparing for global-scale risks.

Looking Ahead

The study underscores the need to treat droughts and floods not as isolated disasters, but as connected outcomes of global climate cycles. As ENSO continues to interact with longer-term ocean patterns and a warming climate, the synchronization of water extremes may become even more relevant for planning and adaptation.

Understanding these connections is not just a scientific achievement. It is a crucial step toward managing water, food, and risk in an increasingly interconnected world.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025AV001684