When Lightning Strikes Models of Multi-Ignition Wildfires Could Predict Catastrophic Events

Wildfires usually begin with a single spark — a lightning strike, a downed power line, or human activity. But some of the most destructive wildfires on record didn’t start that way. Instead, they began as multiple fires igniting separately, often miles apart, before eventually merging into one massive and uncontrollable blaze. These are known as multi-ignition wildfires, and new research shows they play a far larger role in extreme fire seasons than previously understood.

A recent study published in Science Advances takes a deep look at how these fires form, how they behave, and why they are so dangerous. The research was led by scientists from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and the University of California, Irvine, along with several collaborators. Using advanced satellite data and high-resolution climate models, the team explored how clusters of individual fires interact with the atmosphere and with each other — sometimes creating conditions that allow them to grow into record-breaking fire complexes.

What exactly are multi-ignition wildfires?

Multi-ignition wildfires occur when two or more separate fires ignite around the same time and later merge into a single, much larger fire. These ignitions are often caused by dry lightning storms, which can spark dozens of fires during a single weather event. While many of these fires are usually extinguished quickly, some escape containment and begin spreading simultaneously.

The study found that multi-ignition fires are not common, but when they do happen, their impact is enormous. In California, for example, multi-ignition fires make up only about 7 percent of all recorded wildfires. Despite their rarity, they account for around 31 percent of the total burned area in the state. This imbalance highlights how a small number of complex fires can dominate an entire fire season.

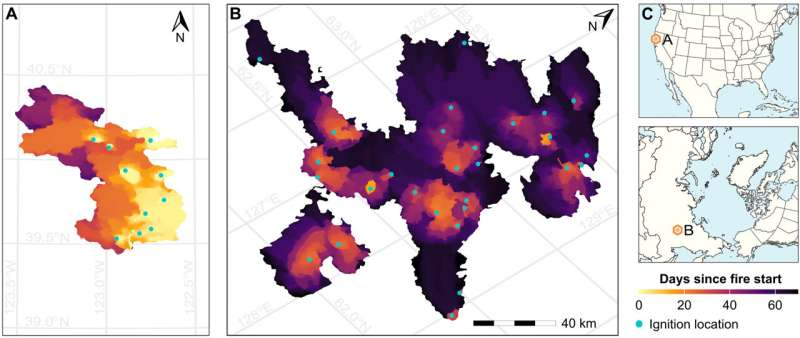

One of the most striking examples is the 2020 August Complex fire in Northern California. The fire began with 10 separate lightning-caused ignitions that eventually merged into a single fire footprint. It went on to become the largest wildfire in California’s recorded history, burning more than one million acres.

Similar patterns were observed outside the United States. In Yakutia, Russia, a major wildfire in 2021 started with 27 separate ignition points, eventually forming a massive fire complex. These examples show that multi-ignition fires are a global phenomenon, particularly in regions prone to lightning and prolonged dry conditions.

Why multi-ignition fires are so destructive

The researchers found that once individual fires merge, they behave very differently from single-ignition fires. Combined fires tend to spread faster, burn longer, and release much more heat and smoke into the atmosphere. This added energy can intensify local weather conditions, creating a dangerous feedback loop.

Multi-ignition fires also place extreme strain on firefighting resources. Instead of dealing with one fire front, emergency crews must respond to multiple active fronts at the same time, often spread across large and difficult terrain. This makes coordination harder and increases the risk to firefighters, especially when new fires ignite unexpectedly nearby.

Another critical factor is that these fires are more likely to occur during extreme fire weather, when heat, wind, and dryness are already pushing landscapes toward their limits. Under these conditions, even well-planned suppression efforts can be overwhelmed.

The role of fire-triggered thunderstorms

One of the most important findings of the study involves pyrocumulonimbus clouds, which are thunderstorms created by intense wildfires. When a large fire releases enough heat, it generates powerful updrafts that carry hot air, smoke, and moisture high into the atmosphere. This can result in the formation of towering storm clouds similar to regular thunderstorms.

These fire-triggered storms are especially dangerous because they can produce lightning, strong winds, and erratic weather conditions. The lightning generated by pyrocumulonimbus clouds can ignite new fires far away from the original blaze, sometimes dozens of kilometers downwind. Those new ignitions can later merge with existing fires, creating even larger multi-ignition complexes.

The study found that pyrocumulonimbus events are not evenly distributed across the world. Regions such as California, Canada, and Siberia are particularly prone to these fire-storm interactions. This uneven distribution helps explain why certain areas experience disproportionately extreme wildfire seasons.

How scientists tracked and modeled these fires

To understand how multi-ignition fires evolve, researchers relied heavily on remote sensing data. Scientists at UC Irvine used satellite observations to track fire ignition points and follow how individual fires expanded and merged over time. These datasets included detailed information on fire perimeters updated every 12 hours.

The LLNL team then integrated this real-world fire data into the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM), one of the most advanced climate and Earth system models available. This allowed them to simulate wildfire behavior at a kilometer-scale resolution, capturing interactions between fire spread, atmospheric circulation, and heat transfer.

By combining satellite tracking with advanced modeling, the researchers were able to create a comprehensive framework for understanding how fires ignite, merge, and influence weather patterns. This approach moves beyond traditional fire models that treat fires as isolated events.

Why this matters for firefighters and planners

Multi-ignition fires are especially dangerous for firefighters on the ground. When multiple fires burn simultaneously, crews can become surrounded by rapidly shifting fire lines, particularly if new ignitions occur due to lightning from fire-triggered storms. This greatly increases the risk of entrapment and injury.

The new modeling framework developed by LLNL aims to predict where pyrocumulonimbus clouds are likely to form and where new ignitions might occur as a result. With this information, fire managers could potentially anticipate which fires are most likely to merge and become catastrophic.

In the long term, these predictions could help guide early intervention strategies, resource allocation, and evacuation planning. The goal is not only to fight fires more effectively, but also to prevent individual fires from combining into massive complexes whenever possible.

The future of wildfire prediction

The research team plans to improve their models using new observational data from a NASA field campaign scheduled for 2026. This additional data will help refine how fire-atmosphere interactions are represented in simulations.

Beyond firefighting, the models may also play a role in energy infrastructure planning. Large wildfires can disrupt power grids, damage transmission lines, and create cascading failures. By simulating how fires might spread and interact with the atmosphere, planners could better assess risks to energy security and improve system resilience.

Extra context: why lightning-driven fires may increase

As global temperatures rise, scientists expect dry lightning events to become more common in some regions. Dry lightning produces little or no rainfall, meaning lightning strikes are more likely to start fires. When these strikes occur in clusters, the risk of multi-ignition fires increases significantly.

At the same time, longer fire seasons and drier vegetation create conditions where multiple fires can survive long enough to merge. This combination makes understanding multi-ignition fires increasingly important in a warming climate.

The big picture

The study makes one thing clear: multi-ignition wildfires are rare, but they drive the most extreme fire outcomes. By combining satellite observations with advanced climate modeling, researchers are beginning to uncover the mechanisms that turn scattered ignitions into catastrophic fire complexes.

As these tools continue to improve, they offer the possibility of earlier warnings, smarter firefighting strategies, and better protection for communities and infrastructure. In a world where wildfires are becoming larger and more destructive, understanding how and why fires merge may be one of the keys to reducing future losses.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx6477