Tiny Earthquakes Reveal Hidden Faults Under Northern California

Scientists studying very small earthquakes beneath Northern California have uncovered a far more complex tectonic picture than previously understood. By tracking swarms of tiny, low-frequency seismic events, researchers are learning how several hidden fault structures interact deep underground at one of the most geologically complicated regions in the United States. This work focuses on the area where the San Andreas Fault meets the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a region capable of producing devastating major earthquakes.

The research was carried out by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), University of California, Davis, and the University of Colorado Boulder, and it has been published in the journal Science. The findings highlight how much remains unseen beneath Earth’s surface and why understanding those unseen structures is critical for assessing seismic risk.

A Complex Meeting Point of Tectonic Plates

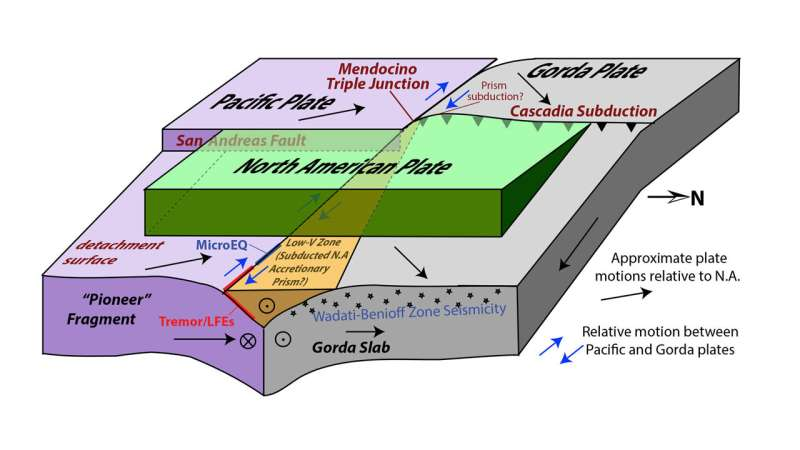

The focus of the study is the Mendocino Triple Junction, located offshore of Humboldt County, Northern California. This is one of the rare places on Earth where three major tectonic plates meet:

- The Pacific Plate, moving northwest

- The North American Plate

- The Gorda Plate, part of the larger Juan de Fuca plate system

South of the triple junction, the Pacific Plate slides past the North American Plate, forming the San Andreas Fault system. North of the junction, the Gorda Plate moves northeast and dives beneath the North American Plate in a process known as subduction, which defines the southern end of the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

On maps, this tectonic setup often looks like three clean lines intersecting. But underground, the reality is far more tangled.

Why Traditional Models Fell Short

For decades, scientists relied on surface fault traces and larger earthquakes to infer what was happening deep below. However, some observations did not fit existing models. One striking example was a magnitude 7.2 earthquake in 1992 that occurred at a much shallower depth than expected for that part of the plate boundary.

This raised an important question: if the plates are arranged the way scientists thought, why was this earthquake so shallow?

The answer, it turns out, lies in structures that are invisible from the surface.

Using Tiny Earthquakes as a Subsurface Map

The research team turned their attention to low-frequency earthquakes, sometimes called micro-earthquakes. These events are thousands of times weaker than earthquakes humans can feel, but they occur frequently where tectonic plates slowly rub or slide past one another.

Using a dense network of seismometers across the Pacific Northwest, the scientists tracked swarms of these tiny earthquakes in remarkable detail. Because these events tend to cluster along active fault surfaces, they act like breadcrumbs, revealing the shape and movement of structures deep underground.

This approach allowed the researchers to “see” beneath the surface in a way that traditional earthquake analysis cannot.

A New Model With Five Moving Pieces

One of the most important outcomes of the study is a revised tectonic model for the Mendocino Triple Junction. Instead of just three interacting plates, the region actually involves five moving pieces, two of which are completely hidden from view.

These include:

- A fragment of the North American Plate that has broken off and is being dragged downward along with the subducting Gorda Plate at the southern end of the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

- The Pioneer fragment, a blob of rock being pulled beneath the North American Plate by the northward-moving Pacific Plate.

The Pioneer fragment is especially interesting. The fault boundary between it and the North American Plate is nearly horizontal, meaning it does not appear as a traditional fault line at Earth’s surface. This makes it effectively invisible without seismic data.

Geologically, the Pioneer fragment was once part of the Farallon Plate, an ancient tectonic plate that used to run along the western edge of North America before breaking apart and mostly disappearing beneath the continent.

Confirming the Model With Tidal Forces

To test whether their interpretation was correct, the researchers examined how these tiny earthquakes responded to tidal forces. Just as the Moon and Sun create ocean tides, their gravitational pull also places subtle stresses on Earth’s crust.

The team found that when tidal forces aligned with the natural direction of plate motion, the number of tiny earthquakes increased. This behavior confirmed that the micro-earthquakes were directly linked to real plate movement, not random noise in the data.

This added confidence that the newly identified fault structures are active and mechanically important.

Solving the Mystery of the 1992 Earthquake

The new model also explains the unusual depth of the 1992 magnitude 7.2 earthquake. According to the revised interpretation, the subducting surfaces beneath the region are shallower than previously assumed.

Earlier models assumed that major faults followed the leading edge of a descending tectonic slab. This research shows that, in this case, the plate boundary is not where scientists once thought it was. As a result, large earthquakes can occur closer to the surface than expected.

Why This Matters for Earthquake Hazards

Understanding the true geometry of faults beneath Northern California is not just an academic exercise. Accurate seismic hazard assessments depend on knowing where faults are located, how they move, and how deep they extend.

If fault boundaries are misplaced in hazard models, predictions about earthquake size, depth, and ground shaking intensity can be off. This is especially important for a region like Northern California, where offshore earthquakes can still pose serious risks to coastal communities.

The findings emphasize that hidden fault structures can play a major role in earthquake behavior, even when they leave no obvious trace at the surface.

A Broader Look at Low-Frequency Earthquakes

Low-frequency earthquakes have become an increasingly valuable tool in modern seismology. Unlike sudden, high-energy earthquakes, these events are associated with slow slip, a process where faults move gradually over days or weeks.

Studying these signals has helped scientists better understand subduction zones, fault loading, and the conditions that may precede large earthquakes. In regions like Cascadia, low-frequency earthquakes are also closely monitored because of their connection to megathrust earthquake cycles.

This study adds another important use for these tiny signals: revealing hidden tectonic fragments and fault geometries that would otherwise remain unknown.

A Clearer Picture, With More Questions Ahead

The research paints a much clearer picture of how tectonic plates interact beneath the Mendocino Triple Junction, but it also raises new questions. How common are hidden fragments like the Pioneer block in other tectonic settings? How do these structures influence long-term earthquake cycles? And how should seismic hazard models be updated to reflect these findings?

What is clear is that even the smallest earthquakes can provide crucial insights into Earth’s most powerful geological processes.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aeb2407