Historic Ocean Treaty to Safeguard and Sustainably Use the High Seas Takes Effect on January 17

A major milestone in global ocean governance is arriving on January 17, when the long-awaited High Seas Treaty officially comes into force. Formally known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement, this treaty is designed to protect and sustainably manage the vast stretches of ocean that lie outside any single country’s control. What makes this moment especially notable is the central role played by Oregon State University (OSU) scientists, whose research helped shape the scientific foundation of the agreement.

The high seas account for roughly two-thirds of the global ocean and nearly half of the planet’s surface, yet for decades they have lacked a comprehensive legal framework for conservation. While international waters support extraordinary biodiversity, they have also been increasingly threatened by overfishing, pollution, climate change, seabed mining, and emerging activities such as deep-ocean aquaculture. The High Seas Treaty represents the first legally binding global effort to address these pressures in a coordinated way.

The treaty’s journey has been a long one. Discussions began more than 20 years ago, reflecting the complexity of balancing conservation, economic interests, and international equity. Momentum finally accelerated in June 2023, when the United Nations formally adopted the treaty text. Once opened for signatures, 81 countries signed within just three days, signaling broad political support. Signing, however, is non-binding. The treaty required ratification by 60 nations to become legally enforceable.

That threshold was reached on September 19, 2025, when Morocco became the 60th country to ratify the agreement. Under the treaty’s rules, it would enter into force 120 days later, setting January 17 as the start date. The first country to ratify was Palau, which did so in January 2024, highlighting strong leadership from small island nations that are often on the front lines of ocean change.

At the heart of this treaty is science, and this is where Oregon State University’s contribution becomes especially significant. Less than two years before the treaty was adopted, OSU scientists led the development of a landmark publication known as The MPA Guide, released in Science in September 2021. This guide provided a clear, evidence-based framework for designing, evaluating, and monitoring marine protected areas (MPAs). MPAs are sections of the ocean designated to limit or prohibit extractive activities such as fishing, mining, and drilling, with the goal of protecting ecosystems and biodiversity.

The MPA Guide was the result of decades of research and collaboration. It was coordinated by Kirsten Grorud-Colvert and Jenna Sullivan-Stack of Oregon State University, who worked with more than three dozen scientists from around the world. The guide established a standardized way to categorize MPAs based on their level of protection, helping governments and international bodies move beyond vague labels and toward measurable conservation outcomes.

This framework has since been adopted by influential organizations. The World Database on Protected Areas, a United Nations-affiliated initiative, now hosts the MPA Guide documents on its Protected Planet platform. In addition, the MPAtlas, an independent authority on ocean protection, uses the guide as the basis for its assessments. These adoptions have helped turn the MPA Guide into a global reference point, directly informing how the High Seas Treaty approaches area-based conservation.

One of the treaty’s most prominent champions is Jane Lubchenco, a Distinguished Professor at Oregon State University and the senior author of the MPA Guide. She has described the treaty as an unprecedented opportunity to protect biodiversity across an area covering nearly half the planet. According to Lubchenco, the high seas contain extraordinary biological richness, but that richness is declining rapidly. The treaty, she argues, demonstrates how science can directly inform pioneering global policy, and why continued scientific input will be essential for successful implementation.

Lubchenco has also emphasized that marine protected areas can deliver ecological, conservation, and social benefits when they are properly designed and supported. However, she stresses that MPAs are not effective by default; they require strong governance, enforcement, and community engagement to achieve their goals.

Beyond natural sciences, the treaty underscores the importance of social sciences. Effective implementation depends on inclusivity across cultures, regions, and economic contexts. Lubchenco has noted that without attention to social dynamics and equity, even the best scientific frameworks can fall short.

Several other OSU researchers contributed to the MPA Guide and, by extension, the treaty’s scientific foundation. Vanessa Constant, then a doctoral student in integrative biology, and Ana Spalding, a courtesy professor of marine and coastal policy, were part of the research effort. Their work highlights how interdisciplinary collaboration is essential for addressing complex environmental challenges like high-seas governance.

As of now, 145 of the United Nations’ 193 member states have signed the treaty, and 81 have ratified it. While the United States signed in 2023, it has not yet ratified the agreement. Ratification matters because only ratifying countries have a formal voice and vote in decisions made under the treaty, including the establishment of new marine protected areas and the regulation of emerging activities that could affect national fisheries or coastal waters. Countries that choose not to ratify effectively give up influence over decisions that may still impact them.

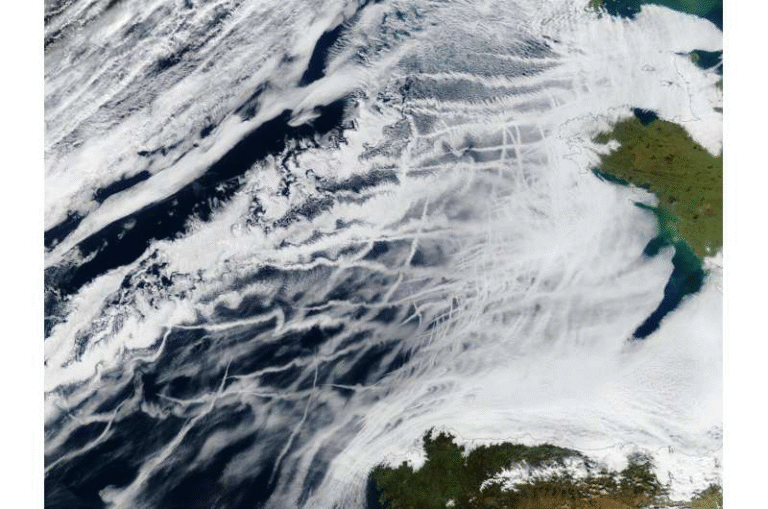

The treaty also introduces new tools for understanding and managing the ocean. Lubchenco recently published an article in Nature Reviews Biodiversity discussing the treaty’s potential, accompanied by a new global ocean map using a Spilhaus projection. Developed in partnership with OSU’s Cory Langhoff and Dawn Wright of Esri, the map presents the ocean as a single, interconnected system rather than a collection of separate basins. It clearly distinguishes between Exclusive Economic Zones, which fall under national jurisdiction, and the high seas beyond them. This visual perspective reinforces the idea that although governance may be divided, the ocean itself is fundamentally connected.

Looking ahead, the High Seas Treaty sets the stage for a new era of international cooperation. It establishes mechanisms for creating MPAs on the high seas, requires environmental impact assessments for potentially harmful activities, and promotes capacity building so that developing nations can fully participate in ocean science and management. While challenges remain—particularly around enforcement and political commitment—the treaty marks a decisive step toward treating the high seas as a shared global responsibility rather than an open-access frontier.

For researchers, policymakers, and anyone concerned about the future of the ocean, January 17 represents more than just a date on the calendar. It is the moment when decades of negotiation, scientific research, and international advocacy finally translate into binding global action for one of Earth’s most critical and least protected ecosystems.

Research references:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abj9958

https://www.nature.com/articles/s44358-025-00124-y

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aef3177