Russell and Moore vs Today’s Analytic Philosophy

Most of us think we already know the origin story. Analytic philosophy was born in early 20th-century Cambridge, with Russell and Moore charging out against the ghosts of Hegel.

It was all about clarity, logic, and kicking out metaphysics, right?

But I want to slow that story down a bit and ask: what were Russell and Moore actually doing in that moment, and why did their project mutate so dramatically once it crossed the Atlantic?

Because if we look more closely, the Cambridge scene wasn’t just a rebellion—it was a subtle reconfiguration of what counts as philosophy.

There were deeper tensions at play: between logic and moral seriousness, realism and anti-authoritarianism, private intuition and public argument.

And some of those tensions are still with us today, even if we don’t always notice them. So let’s start where it all supposedly began—but this time, let’s read between the lines.

What Was Really Happening in Cambridge?

Everyone says G.E. Moore broke with British Idealism. Sure, but how he did it matters. His 1899 paper, The Nature of Judgment, is often remembered for one thing: rejecting the notion that reality is somehow “spiritual” or dependent on our minds.

But if you dig into it, there’s a more interesting move. Moore wasn’t just denying idealism—he was repositioning epistemic authority. Instead of grounding knowledge in speculative systems, he was saying: look, there are things we just know, and those things matter.

This is where Moore’s so-called “common sense realism” gets a bad rap. It’s easy to laugh off his list of things he’s certain of—like “Here is a hand”—but those lists weren’t naive.

They were a strategic response to what he saw as philosophical overreach. Moore thought the authority of philosophy had become too detached from actual human judgment.

So when he says we know external objects exist, he’s not being simplistic. He’s calling out a discipline that had, in his view, forgotten what it’s like to be certain.

But let’s not forget: Moore wasn’t working in a vacuum.

He was part of a specific institutional culture—Cambridge, the Apostles, the long shadow of moral philosophy. That matters. The rebellion against Idealism wasn’t just metaphysical—it was also moral.

There was a sense that the grand systems of the 19th century had lost their grip on real human life, and Moore’s realism was a way of pushing philosophy back into the realm of the ordinary, the grounded, the knowable.

That’s a very different motivation from, say, Carnap’s later project, which wanted to formalize science and strip away all ambiguity.

Now enter Russell. His trajectory is more familiar, but still often flattened. He moved from neo-Hegelianism to logicism pretty quickly, but I think we often skip over how messy that transition actually was.

In The Principles of Mathematics (1903), Russell’s writing still breathes metaphysical air—even though he’s arguing that math is reducible to logic, he’s also making claims about the structure of reality that aren’t purely formal.

Here’s a good example: Russell’s theory of descriptions in “On Denoting” (1905) is usually treated as a clean logical maneuver, but he introduces it by worrying about what kinds of things actually exist.

Does “The present King of France is bald” refer to anything at all?

This isn’t just semantics—it’s a metaphysical anxiety about reference and existence. And that anxiety never quite goes away.

Plus, Russell’s early metaphysics is still haunted by his training. He talks about logical “facts” as if they’re ontological primitives, which feels closer to Bradley than we might like to admit.

That’s not a failure—it’s a sign that analytic philosophy didn’t start with a clean break, but with a bunch of half-resolved tensions.

Let’s also talk about style and culture for a moment.

What Russell and Moore were doing wasn’t just changing philosophical content—they were changing what it meant to write and argue like a philosopher. There’s a reason their prose is so stripped down, almost defiant.

In the Edwardian context, this was a kind of anti-theological, anti-authoritarian performance. Think about how different that feels from the German tradition at the time, or even from later American analytic work, which became more technical, more institutionalized, more bureaucratic in a way.

Cambridge in the early 1900s was still small, still intimate, and full of moral seriousness. The idea that philosophy had a duty to be clear wasn’t about aesthetics—it was about integrity.

That’s something we sometimes lose when we treat early analytic philosophy as just the beginning of a technocratic lineage. These guys weren’t trying to build a toolbox. They were trying to rescue philosophy from what they saw as a descent into mysticism, theology, or worse—irrelevance.

So here’s the claim I want to leave hanging: Moore and Russell didn’t invent analytic philosophy as a “method.” They redefined philosophy’s moral purpose. And that original motivation didn’t survive intact when the tradition migrated elsewhere.

What Changed When Analytic Philosophy Left Europe?

So, Cambridge lit the match, but the flame didn’t stay there. By the 1920s and ’30s, something interesting happens: the analytic tradition jumps continental lines and begins to reshape itself in Vienna and then, more radically, in the United States. And here’s what’s key: this wasn’t a linear transmission.

It wasn’t just “Cambridge, then Vienna, then Harvard.” The migration transformed the philosophical DNA in real ways—especially the sense of what philosophy was for.

Let’s start with the Vienna Circle. They were clearly inspired by Russell and Wittgenstein, especially the Tractatus, but they read it in a very particular way. What the Cambridge crowd took as deeply puzzling—even mystical—got filtered through the lens of scientific empiricism.

Wittgenstein’s famous line, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” gets recast as a kind of positivist boundary-drawing.

For Schlick and Carnap, it became a license to cut metaphysics out of the picture entirely.

But that reading doesn’t quite track with the Cambridge Wittgenstein. Think of Frank Ramsey—he saw the Tractatus as brilliant but unstable, maybe even ironic. He famously called it “a kind of nonsense.” There’s a reason Wittgenstein pivoted away from it later in Philosophical Investigations—he felt that its view of language was too rigid, too monolithic.

So while the Vienna Circle turned to logical syntax and verification theory, the British branch was already starting to explore the limits of formalism.

Carnap’s Logical Syntax of Language (1934) is a perfect crystallization of the Vienna mindset. It’s dazzling in its clarity and ambition, but it also makes a bold metaphilosophical move: let’s replace questions about what language means with questions about how language is structured.

That’s a clean break from Moore’s moral seriousness or Russell’s ontological worries.

Suddenly, philosophy looks like a kind of scientific engineering project, one that builds ideal languages instead of interpreting ordinary ones.

Then comes the big shift: the exodus to America. Carnap and other émigrés land in U.S. universities just as the academy is expanding, and they bring this new model of philosophy with them—rigorous, deflationary, and mathematically flavored.

It fits. U.S. academia, especially during the Cold War, was deeply invested in science and clarity, and analytic philosophy became a natural ally. But here’s the twist: it wasn’t Moore or even Russell who defined American analytic philosophy—it was Carnap and his heirs.

Harvard and UCLA, for instance, weren’t just importing European ideas.

They were domesticating them. Carnap ends up in Chicago and UCLA, and suddenly you’ve got a whole generation of philosophers—Quine, Hempel, Reichenbach—absorbing that analytic ethos but tweaking it.

Quine famously breaks with Carnap on the analytic/synthetic distinction, but he still shares Carnap’s sense that philosophy should aim to work alongside the sciences, not above or beyond them.

And that shift matters. American analytic philosophy becomes disciplinary in a new way. It aligns itself with logic, cognitive science, even linguistics. It professionalizes. The kind of work Moore and Russell were doing—philosophy as a kind of existential clarity project—starts to look quaint.

Instead, analytic philosophy becomes the science-adjacent wing of the humanities, and that’s still how a lot of people outside the field see it today.

But it’s not just about method—it’s about what questions are allowed. Think about how long ethics was sidelined in mainstream analytic journals in the U.S. Or how metaphysics became something of a taboo until the Kripkean revival.

Those weren’t just shifts in taste.

They were downstream from this new institutional culture, one that saw philosophy primarily as conceptual clarification, not as moral or existential inquiry.

In short, once analytic philosophy leaves Europe, it doesn’t just travel—it transforms. It becomes more formal, more professionalized, and frankly, more bureaucratic.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing—there’s power in rigor. But it’s a reminder that philosophical style is always partly shaped by institutional context. And when the context changes, the philosophy changes too.

What Does “Analytic Philosophy” Even Mean Today?

Here’s where things get weird. If you look around today, it’s not clear that analytic philosophy is a unified movement at all.

In fact, it might be more accurate to say it’s a fragmented family of styles—related more by ancestry than by shared methods or aims.

Let’s start with metaphysics. For decades, analytic philosophers avoided it like the plague. But now, it’s booming again. You’ve got work on possible worlds, grounding, ontological dependence—terms that would’ve sounded bizarre to someone like Moore. Think of Kit Fine, Karen Bennett, or Jonathan Schaffer.

These folks are doing highly abstract work, often using tools developed in formal logic, but they’re asking questions that look a lot like old-school metaphysics.

How did we get here?

One answer is Kripke. His Naming and Necessity (1970) cracked the door open. Suddenly it was okay to talk about metaphysical necessity again—as long as you did it with modal logic and a few rigid designators. The revival of serious metaphysical inquiry in analytic circles starts there, and it’s only accelerated since.

Then there’s ethics. For years, it was the forgotten child of analytic philosophy—too messy, too subjective.

But now?

You’ve got people like Derek Parfit doing work that’s both analytically rigorous and deeply moral. His On What Matters is a 1,400-page monster that tries to unify Kantianism, consequentialism, and contractualism using pretty technical argumentation.

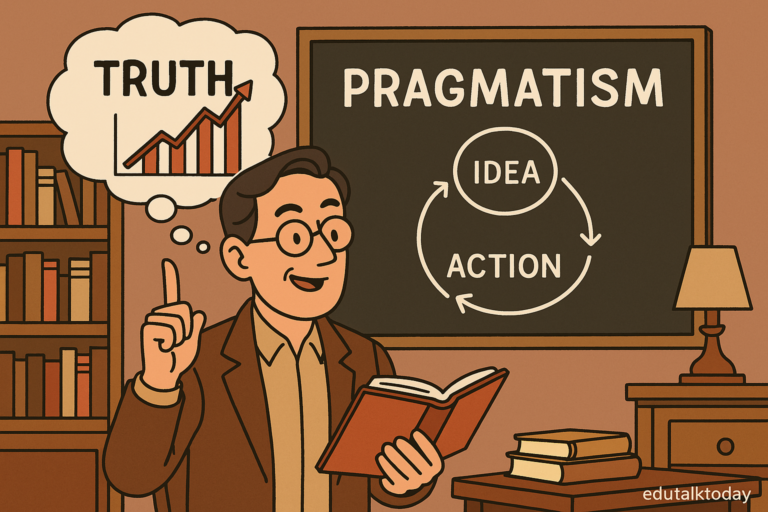

It’s a strange blend: moral seriousness wrapped in formal precision. In a weird way, Parfit is closer to Moore than he is to Carnap, even though they’re decades apart.

We also have a rise in meta-philosophy—philosophers asking what analytic philosophy is, whether it has a method, and whether the label still means anything. Timothy Williamson, for example, argues that philosophy isn’t so much a distinctive discipline as a kind of extension of good reasoning.

His book The Philosophy of Philosophy is a quiet attempt to de-mystify what we do. But even that gesture—trying to define the field—is a symptom of something. If we have to ask what analytic philosophy is, maybe it’s because it’s no longer obvious.

Add to that the fact that analytic methods have seeped into other traditions. There’s a generation of phenomenologists, for instance, who write with more clarity and structure than many so-called analytics.

And you’ve got work in Indian, Chinese, and African philosophy that uses logical analysis to handle questions about mind, normativity, and metaphysics. So if “analytic” just means “clear and rigorous,” well—those aren’t exclusive properties anymore.

In fact, the label might now be more sociological than philosophical. It tells you where someone got their PhD, which journals they publish in, who they cite. It doesn’t necessarily tell you how they think or what they care about. That’s fine—as long as we acknowledge it.

But it does raise a provocative question: if analytic philosophy has no shared method, no shared canon, and no shared goals, is it still a tradition—or just a convenient name for an academic tribe?

I don’t have a clean answer. But I think it’s worth asking, especially if we want to understand where the field goes from here.

Final Thoughts

If we trace the story from Moore and Russell to the present, one thing becomes clear: analytic philosophy didn’t start as a method—it started as a moral and intellectual stance. It was about seriousness, precision, and a rejection of bloated systems. But over the decades, that stance got translated, professionalized, and splintered across continents and institutions.

What we’re left with now is a tradition that’s incredibly diverse but also a little unsure of itself. And maybe that’s okay. Maybe it’s a sign that analytic philosophy is still alive, still evolving. But if we want to understand it—and keep it meaningful—we need to keep asking: not just what do we do, but why are we doing it this way in the first place?