How Analytic Philosophy Became a Global Tradition

When we talk about the spread of analytic philosophy—from Cambridge lecture halls to classrooms in São Paulo, Delhi, and Tokyo—we usually tell a pretty clean story: clarity wins, logic triumphs, the method spreads. But I’ve come to think that’s way too neat.

The real story is messier and a lot more interesting. Analytic philosophy didn’t just win on merit—it traveled through academic infrastructure, political power, and strategic adoption. Institutions mattered.

So did language. And maybe most importantly, analytic philosophy became a tradition only after it had already started spreading.

So in this post, I want to unpack how we got from Moore and Russell’s rebellion in the early 1900s to a global network of departments teaching possible worlds semantics and Gettier cases.

Not just what analytic philosophy is, but how it became a dominant intellectual culture—through very specific historical, institutional, and global mechanisms.

How It All Started ( From Cambridge to Harvard )

Let’s back up. Analytic philosophy didn’t start as some grand movement with a global vision. It started, in large part, as a local turf war in early 20th-century Britain. G.E. Moore and Bertrand Russell weren’t trying to found a global tradition—they were trying to kill off British Idealism.

And they succeeded. But not because realism was more “logical” in some timeless sense.

It was because the intellectual climate was already shifting—toward science, empiricism, and the kind of clarity that fit well with the rising prestige of mathematics. Moore’s Principia Ethica (1903) and Russell’s work on denoting (1905) were timed just right, not just philosophically but institutionally. Cambridge was ready for it.

Here’s the twist that often gets overlooked: what we now call “analytic philosophy” was not a unified tradition in its early decades.

It was a patchwork of projects, held together more by family resemblance than any shared method.

Just look at the early divergence between Russell’s logicism and Wittgenstein’s later language games. Or consider how Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic (1936) turned the Vienna Circle into British common currency—by flattening and simplifying it, honestly.

Meanwhile, over in the U.S., the story wasn’t one of adoption but reinvention. Harvard had its own pluralist scene going on—think of C.I. Lewis, who never fully bought into logical positivism.

And Quine?

He didn’t just import analytic philosophy from Europe; he reshaped it. His attack on the analytic/synthetic distinction in “Two Dogmas” (1951) was a direct blow to the logical empiricist foundations of the very tradition he helped define.

But here’s something even more important: by the mid-20th century, the label “analytic philosophy” started to congeal into something real—but only retroactively.

You didn’t see early Russell or Moore walking around saying, “I’m an analytic philosopher.”

That category really solidified through people like Rorty (ironically) and later historians like Soames, who wrote the canon back into existence.

It’s what you could call a tradition after the fact—an identity constructed to unify a loose network of methods and styles that, at the time, were pretty diverse.

And this is where it gets fascinating. Once the tradition became recognizable—codified through textbooks, curricula, and departmental lines—it became exportable.

You could teach “analytic philosophy” now, because it had a canon: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein, Quine, Kripke, etc. That canon started showing up in syllabi not just in Oxford and Harvard, but in Sydney, Cape Town, and Buenos Aires.

To be clear, this wasn’t just philosophical excellence on parade. It was about pedagogical legibility.

Analytic philosophy became a way of organizing philosophy education: short papers, problem cases, clear argument structure. You could teach it. You could grade it. It fit the academic model.

That made it reproducible—and replication is how traditions scale.

So by the 1950s and ’60s, what started as local debates about meaning and logic in elite Western institutions had become an academic brand, ripe for export.

But the real machinery that made it global?

That’s what we’ll dig into next—because the postwar world was very good at exporting intellectual traditions. Especially ones packaged in English.

How Analytic Philosophy Became a Global Power Language

By the 1950s, analytic philosophy wasn’t just a method or a style—it was becoming an institutional ecosystem.

What made it global wasn’t just the arguments themselves. It was the infrastructure around them: journals, departments, conferences, funding networks, language dominance. The Cold War helped too—but more on that in a minute.

Let’s start with a not-so-obvious player: the Ford Foundation.

In the decades after WWII, Western foundations—Ford, Rockefeller, and others—began funding higher education projects around the world.

They didn’t always care about philosophy per se, but they did care about building rational, modern, “scientific” institutions in developing countries. Analytic philosophy, with its formal tools and friendly proximity to the sciences, fit perfectly into that vision.

Take Latin America. The Ford Foundation directly supported programs that helped bring figures like Carnap and Reichenbach into contact with South American scholars.

Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico saw the rise of analytic-influenced programs in logic, philosophy of science, and epistemology—often within a broader goal of “modernization.”

People like Mario Bunge and Gregorio Klimovsky took analytic tools and applied them to contexts that were deeply local—sometimes even politically charged.

But the real kicker was language. English was the delivery mechanism. And that changed everything.

If you wanted your work to get noticed internationally—to be cited, debated, reviewed—you wrote in English.

The top journals (like The Philosophical Review, Mind, Nous, Journal of Philosophy) operated in English, with implicit standards that favored a particular style of argument: short, tight, rigorous, and typically ahistorical. It wasn’t just that analytic philosophers happened to write this way. It’s that this was what counted as “clear” or “publishable.”

So let’s call this what it is: epistemic gatekeeping.

Think of the effect this had on departments in, say, Poland or India or Japan. If you wanted your grad students to get international fellowships or publish in top journals, you had to train them in the analytic idiom. That meant setting aside local traditions—or at least translating them into analytic terms.

In practice, this created what I’d call a double pressure:

- Local scholars had to learn and teach a tradition that was historically disconnected from their own.

- They had to present their research through analytic categories—epistemology, semantics, modal logic—even if their core concerns were philosophical problems rooted in different cultural or metaphysical frameworks.

To put it bluntly: analytic philosophy became a passport, and English was the visa office.

Now, throw Cold War politics into the mix. The U.S. and its allies saw analytic-style reasoning as rational, scientific, and politically neutral—exactly the kind of thing that aligned with liberal democratic values.

Logical positivism, stripped of its political roots in European socialism, became a symbol of anti-dogmatism. Departments funded in countries like Turkey, Taiwan, and Pakistan were often nudged toward curricula that aligned with Western ideals of reason and objectivity.

Of course, not all of this was imposed. Plenty of scholars adopted analytic tools because they genuinely found them useful—and many did brilliant things with them (we’ll get to that in Part 4).

But the point here is: the spread of analytic philosophy wasn’t just intellectual diffusion. It was part of a wider system of academic power, shaped by geopolitics, funding streams, and the global dominance of English.

One final twist: even within analytic philosophy, the infrastructure started to harden. By the 1970s, the journal system began narrowing what counted as “serious work.”

Philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and formal epistemology dominated.

Metaethics and decision theory surged. Meanwhile, whole swaths of philosophical work—continental theory, historical scholarship, non-Western traditions—got classified as “other.”

The result? A global philosophical environment where analytic philosophy wasn’t just an option—it became the default.

But defaults don’t stay default forever. And in the last few decades, we’ve seen something new emerge: local reinventions, hybrid practices, and even critiques from within the analytic framework itself.

Let’s turn there next.

How Analytic Philosophy Gets Localized

So here’s where things get really interesting.

Despite its structured spread and dominant tone, analytic philosophy didn’t just flatten everything in its path. In a lot of places, it got remixed—blended with local traditions, political goals, and epistemic frameworks in surprisingly creative ways.

Let’s start with India.

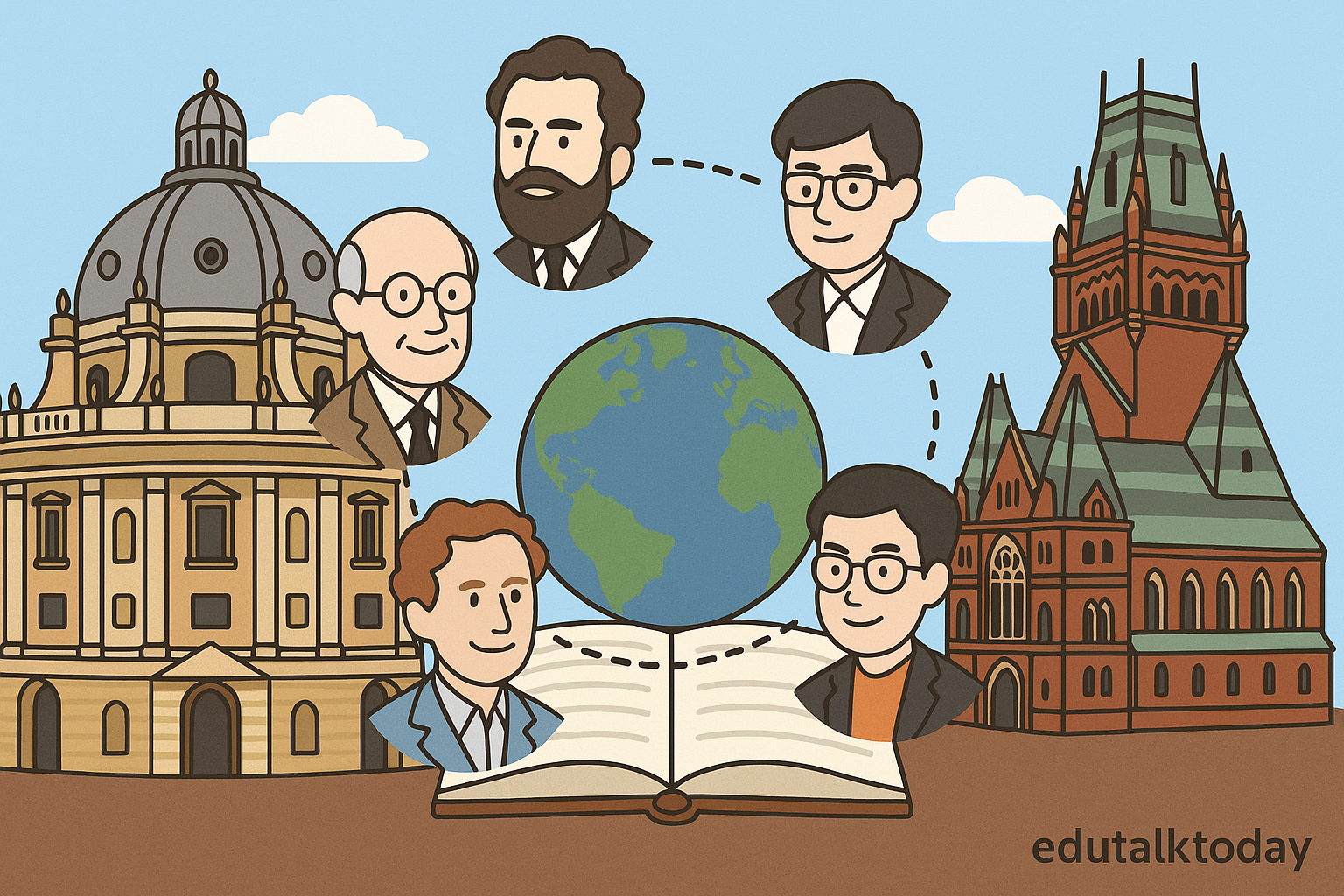

In some Indian universities—like JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University) or the University of Hyderabad—you’ll find philosophers trained in hardcore analytic methods engaging seriously with classical Indian philosophy, particularly Nyāya and Mīmāṃsā logic.

These aren’t just historical side interests. They’re real-time debates on inference, perception, justification, and meaning.

Scholars like B.K. Matilal brought Oxford-trained analytic tools into conversation with Sanskrit texts—and made them speak to each other.

The result?

A re-framing of Indian epistemology in terms analytic philosophers could work with, without diluting the substance.

This wasn’t just translation—it was a kind of philosophical code-switching.

Over in East Asia, something similar has been happening. Philosophers working in Japan, South Korea, and especially China have used analytic tools to engage with Confucian moral theory, Buddhist metaphysics, and more.

In China, for example, there’s been a surge of interest in using analytic ethics to analyze Confucian role ethics—taking the logic of family and social roles and asking: How would these map onto, say, Rawlsian contractualism or Parfit’s reasons-based framework?

The result isn’t always a clean synthesis—but that’s the point. These efforts show that analytic philosophy isn’t a finished product. It’s a living interface.

Then there’s Latin America, where things get even more overtly political.

In Argentina, scholars like Eduardo Rabossi used analytic tools to work on human rights and transitional justice, especially after the military dictatorship.

The precision of analytic reasoning gave weight to legal and moral arguments—especially when philosophical clarity could translate into public and institutional trust. In Brazil, debates around race, epistemic injustice, and Afro-Brazilian thought are now intersecting with analytic epistemology in ways that push the tradition into new territory.

We’re not talking about a passive adoption here. These are strategic appropriations. Scholars are using the prestige of analytic philosophy to do two things at once:

- Make local intellectual traditions legible in global academic forums, and

- Challenge the narrowness of what “counts” as analytic work.

There’s a real shift happening.

Departments across the Global South (and even parts of Europe) are producing analytic philosophers who don’t treat the Anglophone canon as sacred.

They’re trained in Kripke and Williamson, sure—but they’re also asking, “What can this do for our questions? And what doesn’t it let us say?”

Even within the U.S. and U.K., we’re seeing this expansion. Look at the rise of analytic feminist philosophy, analytic philosophy of race, or analytic theology—each pushing the method beyond its old confines. Hell, even the resurgence of metaphilosophy—people asking what analytic philosophy is, or should be—suggests that the tradition is more unsettled than its image implies.

So the story isn’t one of triumph and takeover. It’s a story of translation, resistance, creativity, and feedback loops. Analytic philosophy went global—but the globe is now talking back.

Final Thoughts

What started as a local rebellion against British Idealism has become a global tradition—but not because it was destined to. It happened because analytic philosophy aligned with systems of power, language, and education that helped it scale. But now that it’s global, it’s no longer just British or American. It’s being rethought, reworked, and, in some places, quietly rebelled against.

And maybe that’s the best sign of all that analytic philosophy is alive. It’s not a dogma—it’s a method under pressure, changing shape, listening, arguing back.

We should keep watching what happens next.