Yellowstone’s Roaming Bison and Their Role in Reviving Ecosystems

Yellowstone National Park is once again in the spotlight, this time not for its geysers or wolves, but for its bison.

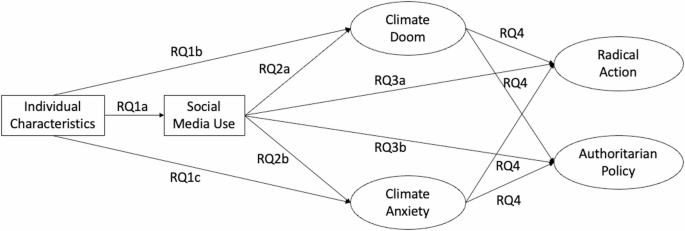

A major study published in Science on August 28, 2025 has revealed that Yellowstone’s large, free-moving bison herds are reshaping the park’s ecosystems in ways that many had not fully appreciated. Conducted by scientists from Washington and Lee University, the National Park Service, and the University of Wyoming, this research takes a straightforward look at what happens when thousands of bison are allowed to roam, graze, and migrate freely across a vast landscape.

The Scale of Yellowstone’s Bison Recovery

The Yellowstone bison story is a dramatic comeback. By 1902, the population had been reduced to just 23 animals. Today, the park supports around 5,000 bison, a stable number since the mid-2010s. Each year, these animals migrate nearly 1,000 miles along a 50-mile corridor, following the wave of fresh plant growth after the snow melts.

This scale of migration makes Yellowstone unique. Across North America, many restoration projects are reintroducing bison, but these are usually small, fenced herds. While they may preserve the species, they do not recreate the ecological processes that large, free-ranging herds set into motion. Yellowstone is one of the last places where scientists can still observe bison acting as ecosystem engineers across an entire landscape.

What the Researchers Did

The team, led by Bill Hamilton, Chris Geremia, and Jerod Merkle, carried out fieldwork between 2015 and 2022. They established 16 research sites across different habitats: valley bottoms (which develop into “grazing lawns”), nearby dry slopes, and wetter, high-elevation areas.

To study grazing effects, they used movable exclosures (small fenced plots rotated every 30 days) and fixed exclosures (permanent fenced plots left ungrazed throughout the season). This allowed them to measure exactly how much plant biomass was consumed and how soil and plant chemistry changed.

But the research didn’t stop there. They paired these plot-level observations with satellite imagery and GPS collars on bison, building a big-picture view of how grazing patterns spread across Yellowstone’s migration routes. In short, they tracked bison movements, measured plant growth, analyzed soil microbes, and studied the chemistry of both plants and soils.

The Nitrogen Cycle Boost

One of the most striking findings was how bison grazing accelerates the nitrogen cycle. Normally, nitrogen moves through ecosystems slowly: plants absorb it from the soil, animals eat the plants, and eventually microbes break down waste and decaying matter to recycle nitrogen back into forms plants can use (such as ammonium and nitrate).

When bison graze, this process speeds up. Their constant clipping of plants stimulates root activity and microbial growth in the soil. Their dung and urine add nitrogen directly back into the system. Together, this creates a loop that delivers up to 150% more nutrients in the regrown plants compared to ungrazed areas.

This means that instead of weakening plant growth, grazing actually makes plants more nutritious. Even though plants regrow to about the same height and mass as those left untouched, their nitrogen content increases dramatically, boosting protein levels for all herbivores in the ecosystem.

Grazing Lawns and Landscape Patterns

Another major result of the study is that bison grazing creates a patchwork, or heterogeneity, across Yellowstone’s valleys. They don’t graze everything evenly. Some places become heavily used “grazing lawns”—short, dense, and nutrient-rich areas—while other patches remain largely untouched.

This variation is important. In landscapes where grazing is uniform and intense, productivity and diversity usually decline, and soils can become compacted. But in Yellowstone, the patchiness ensures that some areas remain refuges while others provide high-quality forage. Across the migration corridor, this results in higher plant biodiversity, stable productivity, and sustainable soil nutrient storage.

The Numbers Behind the Impact

- Timeframe of study: 2015–2022

- Number of research sites: 16 across multiple habitat types

- Bison herd size: ~5,000 animals

- Migration distance: ~1,000 miles traveled annually within a 50-mile corridor

- Nutritional boost: up to 150% higher plant nutrient content in grazed areas

- Population low point: just 23 animals in 1902

These numbers illustrate both the fragility of the species’ history and the enormous ecological influence of their recovery.

Why This Matters for Ecosystem Health

The findings suggest that Yellowstone’s grasslands are functioning better with bison than without them. Their grazing enhances not only the quality of food available to other herbivores like elk and pronghorn but also the entire food web. By enriching the nutritional value of plants, bison indirectly support predators, scavengers, and other species that rely on healthier prey populations.

The study compares this transformation to the Serengeti, where wildebeest migrations dramatically reshaped the ecosystem after their population recovered. In both cases, large herbivore movements across vast distances seem to amplify biodiversity and strengthen ecological processes.

Lessons for Conservation and Rewilding

Most bison conservation efforts today focus on small, fenced herds. While these projects are valuable, they cannot replicate the ecosystem benefits observed in Yellowstone. The study highlights the importance of restoring movement and scale—letting herds migrate freely and create natural heterogeneity across landscapes.

This has broader implications for rewilding projects worldwide. Large herbivores like bison, wildebeest, and caribou have historically shaped their environments through grazing, trampling, and nutrient redistribution. Allowing them to roam over large areas, rather than managing them as if they were livestock, may be key to restoring ecosystem health.

Additional Information: Understanding the Nitrogen Cycle

Since nitrogen plays such a central role in this study, it’s worth briefly explaining how it works. Nitrogen is essential for life—it’s a major component of proteins and DNA. Yet most of the nitrogen on Earth is in the atmosphere as nitrogen gas, which plants cannot use directly.

In ecosystems, soil microbes convert nitrogen gas into plant-usable forms (like ammonium and nitrate) in a process called nitrogen fixation. When animals like bison graze and urinate, they add nitrogen compounds directly into the soil. Microbes then recycle this material, speeding up the return of nitrogen to plants.

This cycling is crucial for plant growth and for the nutritional quality of food available to herbivores. Without it, ecosystems become nitrogen-poor, which limits plant growth and reduces the protein available to animals.

Extra Perspective: Bison as Ecosystem Engineers

Bison are often called ecosystem engineers because their activities reshape landscapes. Besides grazing and fertilizing, they:

- Create wallows: depressions in the ground where they roll, which collect water and form microhabitats.

- Disperse seeds: carrying plant seeds in their fur and dung, spreading vegetation across large distances.

- Influence fire regimes: by grazing heavily in some areas, they reduce fuel loads and may alter how wildfires spread.

Historically, tens of millions of bison roamed North America. Their near-extinction in the 19th century removed these influences, fundamentally changing prairies and grasslands. Yellowstone now provides a rare window into how these ecosystems once functioned.

Implications Beyond Yellowstone

The findings may also have lessons for livestock management and regenerative agriculture. Bison grazing demonstrates how large herbivores can enhance soil fertility and plant nutrition without synthetic fertilizers. Some ranchers are experimenting with “mob grazing” or rotational grazing systems that mimic natural herd movements, aiming to restore soil health and biodiversity.

While domesticated cattle cannot replicate bison migrations perfectly, adopting some of these principles—such as moving herds frequently and creating patchy grazing—may help bring similar benefits to agricultural systems.

Final Thoughts

The recovery of Yellowstone’s bison is more than just a conservation success story—it’s an ongoing experiment showing the power of large animals to rebuild ecosystems. By accelerating the nitrogen cycle, enriching plant nutrition, and creating a mosaic of habitats, bison demonstrate what is possible when wildlife is allowed to move freely and interact with landscapes at scale.

In the end, Yellowstone offers more than scenic beauty. It serves as a living laboratory, reminding us of what was lost when bison nearly disappeared and what can be regained through thoughtful restoration. For anyone interested in the future of conservation, grassland restoration, or rewilding, these findings are both hopeful and instructive.