Strange White Halos on the Ocean Floor Near Los Angeles Reveal Toxic Waste Legacy

For decades, Southern California’s offshore waters were used as an industrial dumping ground.

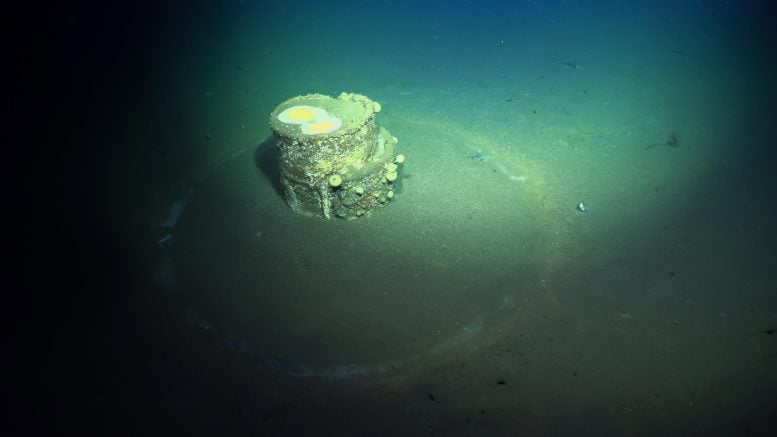

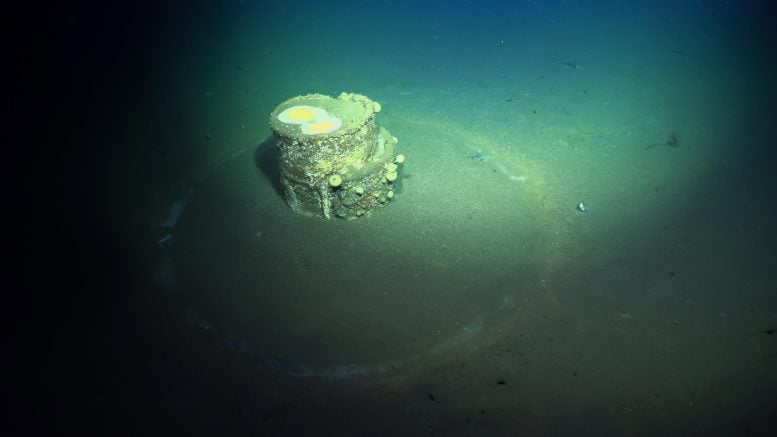

Recent research by scientists at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography has revealed an unsettling discovery: some of the corroded barrels lying on the seafloor are leaking caustic alkaline waste, producing bizarre white halos in the surrounding sediment. This finding shifts our understanding of what was dumped into the ocean and raises new concerns about long-lasting ecological damage.

The Initial Mystery of the Halos

In 2020, striking photographs emerged showing rusted barrels littering the seafloor between Los Angeles and Catalina Island. Many of these barrels were surrounded by pale, halo-like rings in the sediment. At first, scientists suspected the containers held residues of DDT, the infamous pesticide banned in 1972. Because DDT is already known to persist in local sediments and marine life, the possibility that these barrels were filled with it caused alarm.

However, the halos didn’t quite make sense if DDT alone was responsible. The barrels seemed to be producing unusual environmental effects that required deeper investigation.

What the Researchers Found

During surveys in 2021, scientists used the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) SuBastian aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Research Vessel Falkor to collect sediment samples around five barrels. Three of these barrels were surrounded by the mysterious white halos.

To their surprise, sediments inside the halos were hardened like concrete, making core collection nearly impossible. Using SuBastian’s robotic arm, they managed to break off pieces of the crust for analysis.

Laboratory tests revealed the following:

- pH Levels: Sediment samples from halo barrels were highly alkaline, with a pH around 12. Normal seawater is close to pH 8, so this indicated extreme chemical alteration.

- Mineral Composition: The hardened crust was mostly brucite (magnesium hydroxide). This formed when alkaline waste leaked from the barrels and reacted with magnesium in seawater.

- Calcium Carbonate Dust: As the brucite slowly dissolved, it maintained the high pH in the sediment. At the boundary with seawater, calcium carbonate precipitated as a white dust, creating the halo rings.

- Microbial Impact: Microbial DNA was scarce in the halo sediments. The bacteria that survived were from families adapted to extreme alkaline conditions, resembling those found in deep-sea hydrothermal vents or alkaline hot springs. Normal microbial diversity was significantly reduced.

Not Just About DDT

The analysis showed that DDT concentrations did not increase near the barrels. That means the halos were not formed by DDT leakage. Instead, the barrels contained caustic alkaline waste, possibly by-products from DDT manufacturing or from oil refining, both of which were major industries in the region.

It is known that DDT production generated both acidic and alkaline by-products. Acidic waste was not typically stored in barrels, suggesting that alkaline waste was considered hazardous enough to be containerized before being dumped offshore.

This discovery highlights that DDT was not the only dangerous chemical disposed of in these waters. Much of what was dumped remains undocumented, making the full extent of contamination uncertain.

Persistence of the Waste

Many scientists assumed that alkaline waste would quickly dilute in seawater. However, the study found that the waste has remained chemically active for more than 50 years, reshaping the seafloor and creating toxic conditions. The lead researchers concluded that this waste should now be considered a persistent pollutant, similar to DDT, with long-term ecological consequences.

Scale of Dumping in Southern California

The issue is not confined to a handful of barrels. From the 1930s through the early 1970s, at least 14 offshore dumping grounds off Southern California were used to discard industrial and military waste. According to the EPA, materials dumped included:

- Refinery waste

- Oil drilling by-products

- Chemical wastes

- Garbage and refuse

- Military explosives

- Radioactive wastes

Recent surveys in 2021 mapped an area of about 36,000 acres in the San Pedro Basin. They identified nearly 27,000 barrel-like objects and more than 100,000 debris items. The total number of barrels across all sites remains unknown. Even more troubling, surveys have also uncovered WWII-era munitions mixed in with the debris.

Impact on Marine Ecosystems

The ecological effects are still being studied, but the findings are concerning:

- Around halo barrels, microbial diversity is depressed, with only extremophiles surviving in the highly alkaline conditions.

- Previous studies also showed that animal biodiversity around halo barrels is reduced.

- If roughly one-third of barrels have halos, as initial surveys suggest, then thousands of seafloor patches may already be altered into inhospitable zones.

These toxic patches resemble natural vent systems, but unlike natural vents, they are the result of industrial waste and pose unknown risks to the wider ecosystem.

How Scientists Plan to Tackle the Problem

Removing contaminated sediments is considered too risky. The highest concentrations of DDT are buried about 4–5 cm below the seafloor, relatively contained for now. Attempting to dredge or suction these sediments would release a toxic plume into the water column.

Instead, scientists are pursuing alternative strategies:

- Using halos as markers: Since the white rings are reliable indicators of alkaline waste, researchers can map and prioritize these sites for monitoring.

- Microbial experiments: Teams are experimenting with microbes collected from contaminated sediments to see if any are capable of breaking down DDT. Microbial degradation may be the only realistic long-term solution.

Why This Matters Beyond Los Angeles

This research highlights an uncomfortable truth: ocean dumping was widespread worldwide before international bans took effect in the 1970s. Many coasts around the globe likely harbor similar legacies of toxic waste. Southern California’s offshore dump sites are simply among the most studied.

The persistence of alkaline waste also challenges the assumption that ocean dilution neutralizes chemical pollutants. Instead, this case shows that some industrial wastes can remain concentrated and chemically active for generations.

Background: What is DDT?

Since DDT is central to this story, it helps to understand its legacy.

- What is it? DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) is a synthetic pesticide first widely used during WWII to control malaria and typhus.

- Why was it banned? DDT is highly persistent, accumulates in animal fat, and biomagnifies through food chains. It was linked to thinning bird eggshells, population declines in bald eagles and peregrine falcons, and possible human health effects.

- Ban history: The U.S. banned DDT in 1972, though it is still used in limited cases in some countries to control malaria.

- Persistence: Even decades after the ban, DDT residues are still detected in soils, sediments, and marine life, including dolphins and sea lions off Southern California.

Background: Brucite and Alkaline Chemistry

The mineral brucite (Mg(OH)₂) played a key role in the halo formation.

- When alkaline waste leaks, it reacts with magnesium-rich seawater, producing brucite.

- Brucite cements sediments, creating concrete-like patches on the seafloor.

- As it dissolves, it maintains the high pH environment and contributes to continued chemical stress on local organisms.

- At the boundary, calcium carbonate precipitates, leaving the distinctive white rings scientists now use as visual indicators.

Looking Forward

The discovery of halo barrels reshapes how scientists approach the toxic legacy of ocean dumping. Instead of focusing only on DDT, attention must expand to other industrial chemicals, including alkaline waste. Each type of waste has different impacts, and only now are we beginning to understand the full picture.

The lasting ecological consequences of these dumps remain uncertain. What is clear, however, is that waste thought to be inert or diluted has persisted for decades, creating extreme habitats that few organisms can tolerate. This revelation underscores the need for ongoing monitoring, careful research, and new approaches to dealing with historic pollution.