Ultra-Processed Foods: New Study Suggests They’re Not the Villain We Think

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have been a hot topic in nutrition debates for years. They are regularly accused of driving obesity, poor health, and even what some call a modern epidemic of food addiction. Policymakers and health advocates often frame these foods as the biggest dietary threat of our time, pushing for warning labels, taxes, advertising restrictions, and even bans near schools.

But a major new study involving over 3,000 UK adults challenges this black-and-white narrative. Researchers looked closely at what actually drives people to eat more than they need, and their findings suggest that our beliefs about food play as big a role as what’s in the food itself.

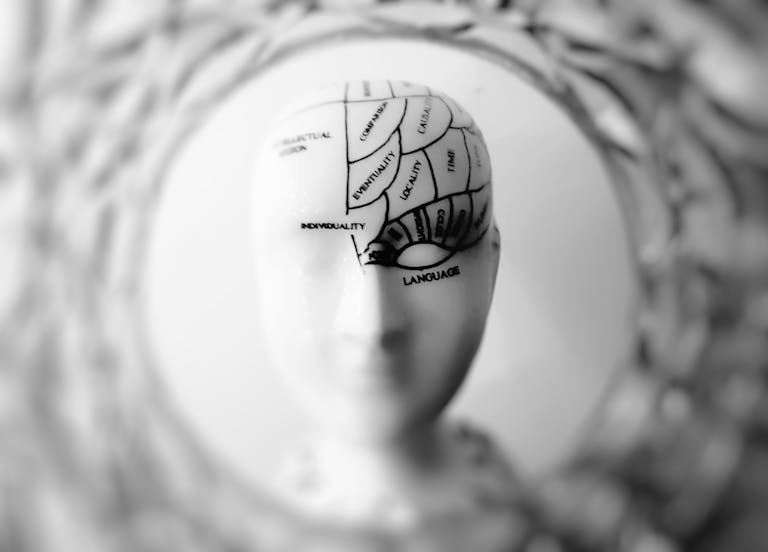

This research shifts the conversation from simply blaming “ultra-processing” to exploring the deeper psychology of eating. Let’s break down what the study uncovered, what it means, and how it fits into the broader debate on food and health.

The Study in Detail

The study, published in Appetite in 2025, was led by nutrition scientist Graham Finlayson and colleagues. It asked a simple but important question: why do people overeat certain foods? Is it because of the nutritional content, the level of processing, or the way we perceive and think about the food?

To answer this, the researchers designed three large online surveys. In total, more than 3,000 UK adults participated. They were shown photos of over 400 different foods—all unbranded to avoid marketing influence. These were everyday items you’d find in a typical UK shopping basket: jacket potatoes, apples, noodles, cottage pie, custard creams, chocolate, biscuits, and ice cream, to name a few.

Participants rated each food on two measures:

- How much they liked it (taste preference).

- How likely they were to overeat it (hedonic overeating, meaning eating for pleasure beyond hunger).

The researchers then compared these ratings against three sets of information:

- The foods’ nutritional profiles (calories, fat, sugar, fibre, energy density).

- The NOVA classification system (which labels foods as minimally processed, processed, or ultra-processed).

- The participants’ perceptions of the foods (whether they seemed sweet, fatty, processed, healthy, bitter, or high in fibre).

What the Researchers Found

The results revealed something surprising: the label “ultra-processed” did very little to explain why people liked or overate foods.

- Nutritional content mattered. People enjoyed calorie-dense foods high in fat or carbs, and they were more likely to overeat foods that were low in fibre but high in calories. This was expected and lines up with decades of nutrition research.

- Perceptions mattered just as much. If people believed a food was sweet, fatty, or highly processed, they were more likely to say they would overeat it—even when the actual nutrient content didn’t fully support that belief. On the flip side, if a food was perceived as bitter or high in fibre, it was less likely to be associated with overeating.

- Combined predictions were strong. Nutritional data alone explained about 41% of the variation in overeating. Adding people’s perceptions boosted predictive power by another 38%, meaning the model could account for 78% of overeating tendencies.

- UPF labels explained very little. Once nutrient profiles and perceptions were factored in, the “ultra-processed” classification added only 2% in predicting food liking and 4% in predicting overeating.

This suggests that simply calling a food “ultra-processed” tells us almost nothing about whether someone will overeat it. Instead, taste, nutrient composition, and personal beliefs are far more powerful predictors.

Why This Matters

The findings are significant because so much of today’s nutrition policy is centered on demonizing UPFs as a category. Some foods in this group—like sugary soft drinks, fried snacks, and candy—are clearly unhealthy when eaten in excess. But the UPF category is broad. It includes not just chips and sodas, but also items like fortified cereals, vegan meat substitutes, protein bars, and even some foods designed for older adults or people with medical dietary needs.

The researchers warn that treating all UPFs as dangerous could backfire. Not every UPF is equally harmful, and some may provide convenience or nutritional benefits. If people are told to avoid all ultra-processed foods, they might miss out on helpful options while still overeating high-calorie snacks.

A More Nuanced Approach

The study suggests shifting away from the “all UPFs are bad” message and focusing instead on education and psychology.

The authors recommend three strategies:

- Strengthen food literacy. Teach people how to recognize what makes food satisfying, what drives cravings, and how to notice personal triggers for overeating.

- Reformulate with purpose. Instead of making bland “diet” foods or indulgent snacks engineered purely for pleasure, design products that are both nutritious and enjoyable.

- Acknowledge motives for eating. People don’t just eat to satisfy hunger. They eat for comfort, social connection, habit, and pleasure. Acknowledging this reality—and offering healthier but still pleasurable alternatives—may help reduce reliance on calorie-dense, low-quality foods.

Why Perceptions Shape Eating

One of the most interesting insights from the study is that our perceptions about food can override the actual nutrient content. If you think something is fatty, indulgent, or overly processed, you’re more likely to overeat it.

This means labels, marketing, and even cultural beliefs all shape how much we eat. For example:

- A plain bag of chips may be perceived as “dangerous” and hard to resist, leading to overeating.

- A bowl of porridge, on the other hand, is liked by many but rarely triggers overeating, perhaps because it’s not associated with indulgence.

This shows how important psychology is in food choice. People don’t just respond to the physical nutrients—they respond to their own mental associations with foods.

The Limits of the UPF Label

The NOVA classification system, which is widely used to categorize foods as ultra-processed or not, has been central in public health discussions. However, the study shows its limits.

The researchers found that the UPF label added almost no predictive power when it came to overeating. That doesn’t mean UPFs are harmless—many are calorie-dense, aggressively marketed, and sold in large portions—but it does mean that the label is a blunt tool.

By lumping together sodas, cookies, and fortified cereals, the UPF category creates confusion. Some of these foods may deserve stricter regulation, but others could play a role in a balanced diet.

The Bigger Picture: What We Already Know About UPFs

This study isn’t saying UPFs are harmless. Past research has repeatedly shown that diets high in UPFs are linked to:

- Obesity

- Type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease

- Poor mental health outcomes

- Increased mortality risk

But these studies often rely on broad UPF categories, making it unclear whether the negative outcomes are due to processing itself, or simply the fact that UPFs often contain more sugar, salt, and fat and less fibre and micronutrients.

Some nutrition experts argue that nutrient quality matters more than whether a food is processed. For example, whole-grain breads or fortified cereals may be technically ultra-processed, but they can be more beneficial than some minimally processed foods high in saturated fat or sugar.

Why This Study Stands Out

What makes this study unique is its focus on individual perceptions of food. Instead of just looking at nutrient data and health outcomes, it digs into how people think about foods, and how those beliefs predict overeating.

This highlights the importance of including psychology and behavior in nutrition research. People don’t eat based on labels alone—they eat based on how food looks, tastes, feels, and fits into their personal goals and social lives.

Final Thoughts

Ultra-processed foods aren’t going away. They’re a huge part of modern diets because they’re convenient, affordable, and often tasty. But instead of labeling them all as villains, this study suggests a smarter approach:

- Pay attention to nutrient quality.

- Recognize the power of perception in shaping eating behavior.

- Avoid blanket rules that may mislead people.

If the goal is healthier eating, then the focus should shift to helping people understand their own triggers, designing better foods, and supporting choices that balance pleasure with nutrition.

This study doesn’t deny that some UPFs are a problem—but it shows that processing alone isn’t the smoking gun.

Research Reference:

Food-level predictors of self-reported liking and hedonic overeating: Putting ultra-processed foods in context – Appetite, 2025