Has Climate Math Been Rigged All Along? New Research Says Yes

A new study has raised eyebrows across the climate science community, suggesting that the way we’ve been calculating fairness in climate pledges has been deeply flawed.

The research, published on September 3, 2025, in Nature Communications and led by Yann Robiou du Pont from Utrecht University, argues that the math behind international climate responsibility has long tilted in favor of wealthy, high-polluting nations.

This discovery could reshape how we think about climate justice, global responsibility, and the future of international climate agreements. Let’s dive into the details of what the researchers found, why it matters, and what it could mean for both major polluters and vulnerable countries.

The Problem With Climate Fairness Calculations

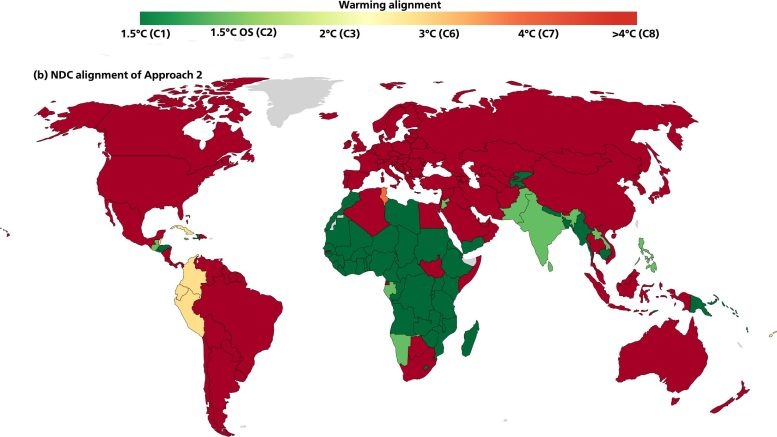

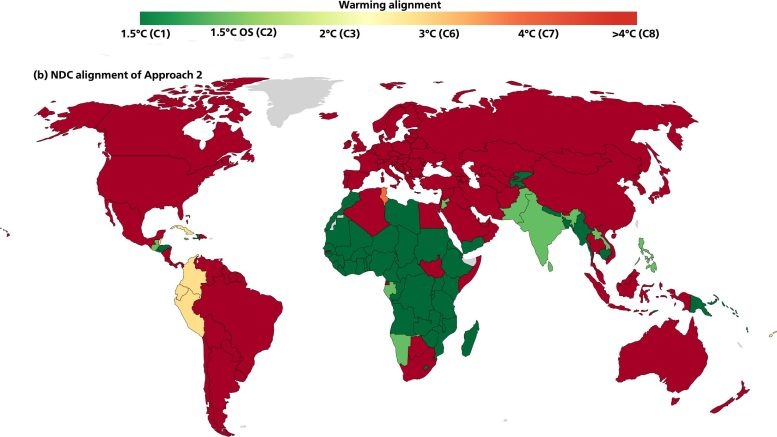

Under the Paris Agreement, countries are expected to do their fair share to keep global warming well below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C. To figure this out, scientists and policymakers have used fair-share allocations, which essentially divide the global carbon budget among countries based on factors such as historical responsibility, capacity to act, and development needs.

But here’s the catch: previous studies and methods for calculating fairness often relied on moving baselines. That means they allowed countries to start their climate pledges from current or rising emissions levels.

The result? High-emitting nations were unintentionally rewarded for past inaction. Because their emissions had already risen so much, the math gave them more “room” to pollute before making steep cuts. Vulnerable, low-emitting countries, on the other hand, ended up carrying more of the burden despite contributing the least to the crisis.

The researchers describe this as a systemic bias baked into fairness assessments, one that has let the largest polluters off the hook for decades.

What the Study Proposes Instead

The team led by Robiou du Pont suggests a new approach they call discontinuous fair-share allocations. Unlike the previous method, which smoothly extended countries’ emission paths from current levels, this one recalculates responsibilities immediately from today.

In other words, it doesn’t matter what your emissions were yesterday; from this point forward, each country is assessed based on historical contributions and capacity to act.

This has major consequences:

- Wealthy, high-emitting countries such as those in the G7, along with Russia and China, would suddenly face much steeper cuts than before.

- Because these cuts are so steep, they can’t realistically be achieved only at home. That means these countries would also need to provide significant financial support to help poorer nations reduce emissions.

This isn’t just a mathematical tweak. It fundamentally reshapes which countries are doing enough and which are falling short. Under this method, countries like the United States, Australia, Canada, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia emerge as having the largest gaps between their current pledges and what’s actually fair.

Why This Matters for Global Climate Goals

We already know that existing pledges are falling short of what’s needed to hit the 1.5°C target. But this research shows that even the way we judge who’s doing enough may be unfair.

By recalculating obligations from the present rather than giving polluters a “grace period,” the study eliminates what the authors call the reward for inaction. This makes the climate effort more honest—countries can no longer hide behind incremental progress while continuing to pollute at high levels.

It also shifts the spotlight within the developed world. Often, discussions about climate justice focus on developed vs. developing nations. But this research shows that even within the developed group, some countries are being unfairly rewarded compared to others that are more ambitious.

Implications for Climate Litigation

One of the most fascinating aspects of this research is its potential impact on climate litigation. Courts around the world are increasingly being asked to weigh in on whether governments’ climate pledges are sufficient and equitable.

A well-known example is the KlimaSeniorinnen case before the European Court of Human Rights, where insufficient climate action was recognized as a human rights violation.

Fair-share studies like this one give courts concrete ways to assess national responsibility. If the old math was biased, then legal decisions based on it may have underestimated some countries’ duties. This new approach could empower courts to demand more aggressive action and accountability.

In fact, just recently on July 23, 2025, the International Court of Justice issued a landmark advisory opinion affirming that countries have a legal obligation to prevent significant harm to the climate system. The court emphasized the need for collective and urgent action, underscoring the growing role of legal systems in enforcing climate justice.

The Bigger Picture: Paying the Climate Debt

The concept of a climate debt isn’t new. Activists and scholars have long argued that countries with the highest historical emissions also have the greatest responsibility to act. This includes not only cutting their own emissions but also funding global mitigation and adaptation efforts.

What this study does is provide a new, more rigorous framework to back up those moral claims with scientific calculations. By holding wealthy, high-emitting countries accountable for their full share—without loopholes—it could drive more ambitious global action.

The authors argue that without immediate and fairer efforts, we’re on track for catastrophic warming levels. But if responsibility is recalculated and enforced, the result could be a more balanced and ultimately more effective global climate strategy.

A Closer Look at Fair-Share Allocations

To understand why this matters, it’s worth digging into how fair-share allocations work. The basic idea is simple: there’s only so much carbon the world can emit if we want to stay under 1.5°C or 2°C. That carbon budget needs to be divided among countries in a way that’s fair.

Principles used include:

- Historical responsibility: How much each country has already contributed to the problem.

- Capacity: Economic and technological ability to reduce emissions.

- Development needs: Recognizing that poorer countries may need more leeway to grow.

Under the old system, these allocations were calculated using “smooth decline paths,” which allowed major emitters to keep their high levels for longer. The new system resets everything at once, producing a sharper but fairer adjustment.

The Role of Courts in Enforcing Fairness

It’s becoming increasingly clear that courts are stepping in where politics has stalled. Governments often hesitate to make painful cuts for fear of economic backlash. But when courts rule that insufficient action violates human rights or international law, it creates a new form of accountability.

The study notes that courts don’t just influence policy—they also shape public opinion and encourage international cooperation by forcing countries to justify their actions under scrutiny.

As climate lawsuits multiply around the world, having a more accurate, equity-based way to measure pledges could make these cases more effective.

Why This Research Feels Urgent

The takeaway is simple: the way we’ve been doing the math has allowed the biggest polluters to delay action, pushing more responsibility onto vulnerable countries. This study corrects that bias and shows just how much more needs to be done by those with the greatest responsibility and capacity.

By removing the hidden reward for inaction, the new method paints a stark picture: if wealthy, high-emitting countries don’t step up with both steeper cuts and financial support, the world will struggle to stay within safe climate limits.

Additional Context: Climate Justice in Practice

To give readers a broader perspective, let’s explore some background around climate justice and why this debate matters:

Climate Justice Principles

Climate justice is about recognizing that the impacts of global warming are not evenly distributed. Vulnerable countries, often the least responsible for emissions, are usually hit the hardest by extreme weather, sea-level rise, and food insecurity.

Financial Mechanisms Already in Place

Mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund were set up to channel money from wealthy nations to poorer ones. But funding levels have consistently fallen short of what’s needed. This study adds more urgency to that gap.

The Paris Agreement’s Weakness

While the Paris Agreement was historic in uniting countries around a common goal, it left too much flexibility in how nations defined “fairness.” This study points out that such flexibility has actually created structural unfairness.

Conclusion

This isn’t just an academic debate. The way we calculate climate fairness has real-world consequences—it shapes policy, influences negotiations, and even determines legal rulings.

The new research led by Yann Robiou du Pont provides a powerful correction to decades of biased math. By focusing on historical responsibility and capacity, it demands that wealthy, high-polluting countries finally take on the urgent role they’ve long avoided.

And perhaps most importantly, it highlights that immediate, fair, and ambitious action is the only way to keep the world on track toward the climate goals we all depend on.