Rethinking Cancer Surgery: Why Preserving Lymph Nodes Could Boost Immunotherapy

For decades, surgeons have often removed lymph nodes near tumors during cancer operations. The idea behind this was straightforward: if the cancer spreads, it usually does so first to nearby lymph nodes, so taking them out might prevent further spread. But new research is challenging this long-standing approach. A team led by the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, based at the University of Melbourne, has revealed that lymph nodes may actually be essential allies in the fight against cancer, not just passive checkpoints.

Their findings, published in two separate papers in Nature Immunology in 2025, show that lymph nodes are more than just filters. They are active training hubs for immune cells—especially for a group of T cells known as stem-like CD8+ T cells. This discovery could reshape how doctors think about cancer surgery and immunotherapy, possibly leading to better patient outcomes.

What the Research Found

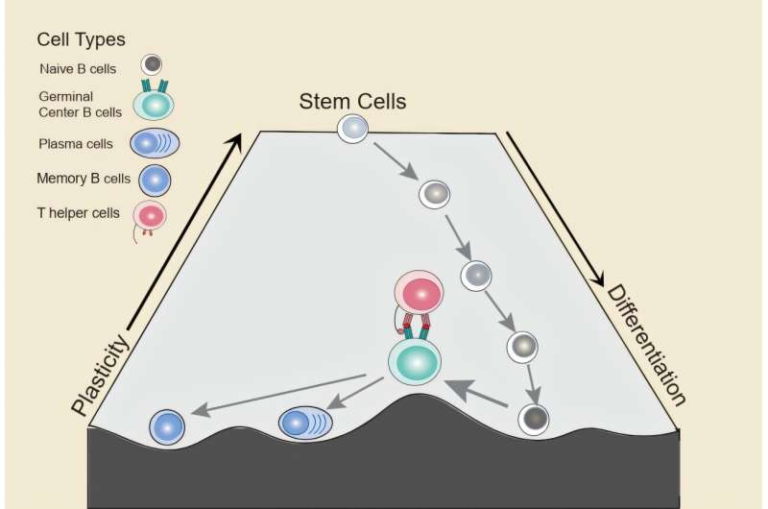

The Doherty Institute studies focused on how lymph nodes influence the immune system’s ability to generate strong, long-lasting responses against cancer and chronic infections. The team demonstrated that:

- Lymph nodes create the right conditions for stem-like CD8+ T cells to persist, expand, and transform into killer T cells that directly attack cancer or infected cells.

- Other immune organs, such as the spleen, do not provide this supportive environment, meaning T cells fail to develop and multiply effectively outside lymph nodes.

- By serving as specialized “training centers,” lymph nodes are essential for checkpoint blockade therapies and CAR T cell therapies, two major approaches in modern cancer immunotherapy.

In short, removing lymph nodes during surgery might unintentionally reduce the effectiveness of these treatments.

Why Lymph Nodes Are Different

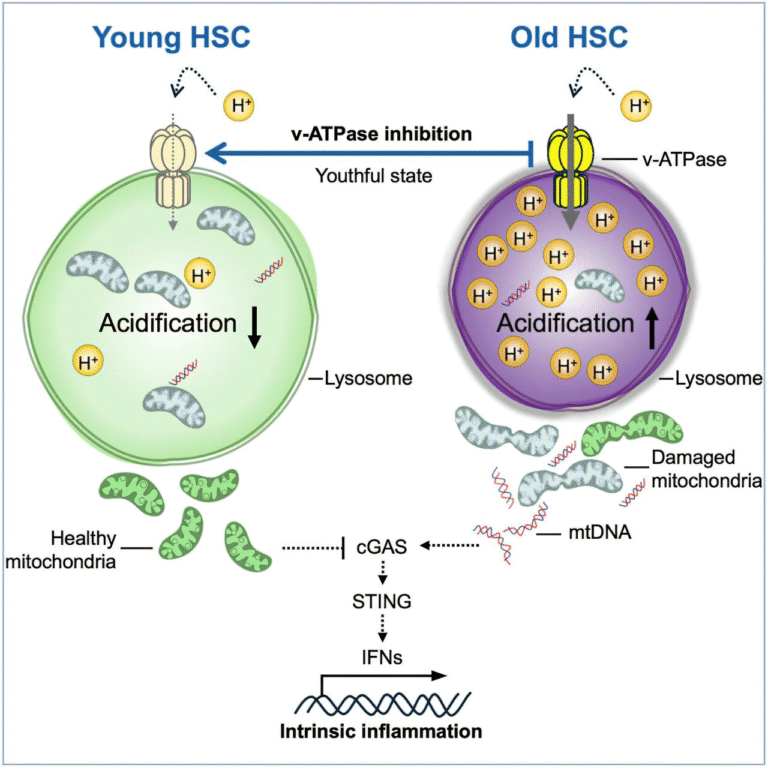

The first study, titled “Lymph nodes fuel KLF2-dependent effector CD8+ T cell differentiation during chronic infection and checkpoint blockade”, showed that lymph nodes—especially tumor-draining ones—provide unique molecular signals and antigen-presenting support. Migratory dendritic cells present antigens in lymph nodes and help stem-like T cells maintain their function while guiding them toward becoming CX3CR1+ effector T cells.

The transcription factor KLF2 plays a crucial role here. Without it, the T cells fail to properly differentiate and expand. This means that lymph nodes are not optional in building a systemic immune response; they are essential.

The second paper, “Lymph-node-derived stem-like but not tumor-tissue-resident CD8+ T cells fuel anticancer immunity”, compared T cells inside tumors to those in lymph nodes. It found that while tumors do contain precursor exhausted T cells, these cells often adopt a tissue-resident program that limits their ability to expand or contribute effectively to tumor control. In contrast, stem-like T cells in lymph nodes continue to fuel tumor infiltration and responses to therapies like checkpoint inhibitors.

Another key finding was the role of TGFβ signaling. In the tumor environment, TGFβ reinforces tissue residency, essentially trapping T cells in a less useful state. In lymph nodes, this restriction is lifted, allowing stem-like cells to thrive and continuously supply fresh fighters to the tumor site.

Why This Matters for Cancer Treatment

These discoveries suggest that the long-standing practice of removing lymph nodes during cancer surgery could backfire by weakening the immune system’s ability to respond to treatment. In many cancers, lymph nodes are removed to reduce the risk of metastasis. But if these nodes are vital immune training centers, taking them out might actually reduce the chances that therapies like checkpoint inhibitors or CAR T cells will succeed.

The implications are significant:

- Surgical strategy may need to be revisited. Instead of routinely removing tumor-draining lymph nodes, doctors may consider preserving them—especially in patients who will receive immunotherapy.

- Timing of therapy and surgery could be adjusted. For example, immunotherapy might work better if given before lymph node removal, allowing immune cells to be primed in the nodes first.

- New therapeutic targets are possible. Pathways such as KLF2 or TGFβ signaling could be manipulated to improve T cell training and enhance treatment effectiveness.

- Patient responses may finally be explained. Not all patients respond equally to immunotherapy. This research shows that the condition of lymph nodes—whether intact, healthy, or compromised—may explain why some patients benefit while others do not.

Toward Clinical Applications

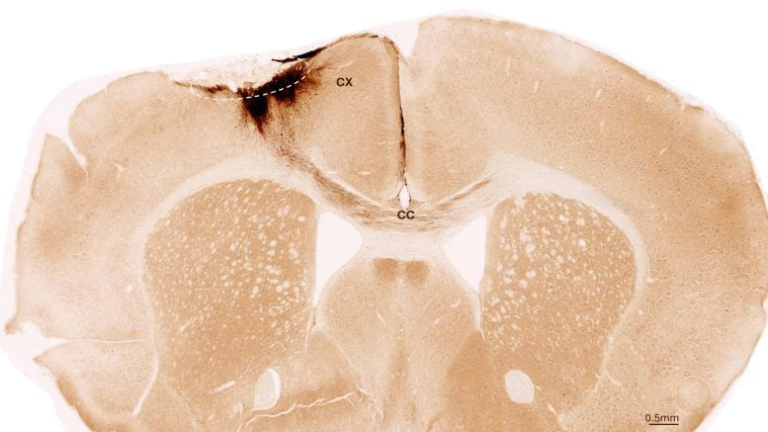

Although these findings are based primarily on animal models, they are already being translated into human studies. At the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, researchers are examining samples from melanoma patients who received checkpoint inhibitors to see whether lymph node activity correlates with therapy success.

If the preclinical results hold true in humans, the impact on clinical practice could be enormous. Instead of focusing only on removing tumors, future cancer treatment might involve strategies to preserve, enhance, or even restore lymph node function.

Funding and Collaborations

This body of work was supported by a wide network of research institutions and funders, including the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC), the Australian Research Council (ARC), Cancer Council Victoria, EMBO, the German Research Foundation, the Helmholtz Association, the Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, and several others. The collaboration involved both Australian and international research teams, highlighting the global interest in improving cancer immunotherapy.

Understanding the Bigger Picture: Lymph Nodes and the Immune System

To fully appreciate the significance of these findings, it helps to understand how lymph nodes work in the first place.

- Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures located throughout the body. They filter lymph fluid and serve as hubs where immune cells meet, communicate, and coordinate responses.

- Inside a lymph node, T cells and B cells are activated by antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells. This is where the immune system learns to recognize and attack pathogens—or cancer cells.

- They act as staging grounds for adaptive immunity, producing armies of specialized cells capable of traveling through the body to fight infection or malignancy.

Without functional lymph nodes, the immune system loses one of its main coordination centers. This is why their removal may have unintended consequences.

A Closer Look at Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has become one of the most promising approaches in cancer treatment. Here are some relevant therapies directly connected to this research:

- Checkpoint blockade therapy: Drugs that block immune checkpoints (such as PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4) help T cells stay active against cancer cells. The Doherty Institute findings suggest these therapies rely heavily on lymph node support to expand effective T cells.

- CAR T cell therapy: This involves engineering a patient’s own T cells to recognize and attack cancer. These modified cells could be more effective if they are expanded or supported in environments that mimic lymph nodes.

- Future strategies: Scientists may develop drugs or techniques that enhance lymph node activity or prevent T cells from being trapped in tissue-resident states inside tumors.

Potential Challenges

While the results are exciting, there are real challenges ahead:

- Lymph node metastasis: Many cancers spread to lymph nodes. Preserving nodes with active metastasis could be risky. Researchers will need to balance the immune benefits of keeping lymph nodes with the danger of leaving behind cancerous tissue.

- Translation from mice to humans: Much of the detailed cellular work was done in mouse models. While the basic biology often translates, human systems can be more complex.

- Clinical logistics: Surgeons and oncologists will need to carefully rethink protocols, including the order and timing of surgeries, biopsies, and therapies.

What Comes Next

The findings open several directions for future research:

- Clinical trials testing whether preserving lymph nodes improves survival and response rates in patients receiving immunotherapy.

- Biomarker development to identify which patients have healthy lymph nodes capable of fueling T cell responses.

- Therapeutic interventions that target the molecular signals identified in the studies (KLF2 pathways, TGFβ signaling, and dendritic cell interactions).

- Immunotherapy scheduling strategies that align with the body’s natural immune “training grounds.”

Conclusion

This research challenges one of the long-standing practices in cancer treatment. Instead of automatically removing lymph nodes near tumors, doctors may soon consider preserving them to boost the immune system’s natural ability to fight cancer. By acting as training centers for stem-like T cells, lymph nodes are proving to be a critical piece of the puzzle in immunotherapy.

As these findings are validated in human trials, they could lead to a major shift in how cancer surgery and immunotherapy are combined, ultimately giving patients better chances of survival.

Research Reference:

Lymph nodes fuel KLF2-dependent effector CD8+ T cell differentiation during chronic infection and checkpoint blockade – Nature Immunology, 2025

Lymph-node-derived stem-like but not tumor-tissue-resident CD8+ T cells fuel anticancer immunity – Nature Immunology, 2025