14,000-Year-Old “Puppies” Turn Out to Be Wolves: What Science Just Uncovered

A fascinating new study has cleared up a long-standing mystery about two remarkably preserved Ice Age “puppies” found in the Siberian permafrost. For years, scientists debated whether these cubs were early domesticated dogs or wild wolves. Now, genetic and chemical analyses have confirmed the truth — these ancient animals were actually wolf sisters, not dogs.

This discovery doesn’t just change our understanding of these specific remains. It also raises new questions about how and when dogs were first domesticated, and it sheds light on what life was like in Siberia during the late Ice Age, more than 14,000 years ago.

The Discovery in the Siberian Permafrost

The story begins near the small village of Tumat, located in northern Siberia. Around 40 kilometers from the settlement, local residents and researchers discovered two nearly perfect canid specimens preserved in frozen permafrost.

The first cub was found in 2011, and the second surfaced in 2015, both unearthed from layers of ice and soil at a site now called Syalakh. These cubs became known as the “Tumat Puppies”, and they stunned scientists because their bodies were almost intact — complete with fur, teeth, and even stomach contents.

Initial studies suggested they might be early domesticated dogs, partly because of their black fur and their proximity to human-modified mammoth bones that appeared to have been butchered or burned. Researchers wondered if these animals might have been companions or scavengers near ancient human camps.

But as new analytical techniques became available, a more detailed investigation began — and the results changed everything.

What the Latest Research Revealed

A research team led by the University of York conducted a multifaceted analysis on the cubs, combining DNA sequencing, chemical testing, and microscopic study of stomach and bone material. The findings were published in the journal Quaternary Research in June 2025.

Here’s what the team discovered:

- Species and Kinship: Both cubs were genetically confirmed to be wolves, not dogs. They were biological sisters, probably from the same litter.

- Age: Their teeth and bone development showed they were around two months old at the time of death — still nursing but already eating solid food.

- Diet: The cubs’ stomachs contained traces of meat and plant matter, showing that Ice Age wolves, like their modern counterparts, had varied diets. One cub had remains of a small bird (a wagtail), while the other had a piece of woolly rhinoceros hide that hadn’t been fully digested.

- Environment: Fossilized plant fragments in their stomachs revealed they lived in a diverse, cold, but vegetated environment, rich with prairie grasses, willow twigs, and shrubs from the genus Dryas.

The presence of woolly rhinoceros remains was especially surprising. A woolly rhino, even a young one, would have been a massive and dangerous target. This finding suggests that Pleistocene wolves might have been larger and more powerful than wolves today — capable of taking down or scavenging large prey.

A Tragic but Natural End

Despite their excellent preservation, the cubs showed no signs of external injuries or predation. Researchers concluded that their deaths were likely accidental. The most probable cause? A den collapse.

It’s believed that the sisters were resting underground, possibly after feeding, when a landslide or permafrost shift sealed their den. The extreme cold quickly preserved their bodies, freezing them in time for more than 14 millennia.

Why They Were Mistaken for Dogs

The earlier assumption that the Tumat Puppies were domesticated dogs came from two main clues:

- Black Fur – It was once thought that the gene responsible for black fur originated only in domestic dogs and later spread to wolves through interbreeding. But this study shows that black coloration existed in ancient wolves, meaning that particular trait isn’t evidence of domestication.

- Proximity to Human Artifacts – The cubs were found near mammoth bones that bore cut marks and signs of burning, likely from human activity. This initially led some archaeologists to think the animals might have been connected to a human settlement or butchering site. However, the study found no traces of mammoth meat in the wolves’ stomachs — meaning they probably didn’t feed directly on human leftovers.

So, while humans might have occupied the same area, there’s no clear evidence that these wolves were living with or being tamed by people.

What Their Diet Tells Us About Ice Age Wolves

The Tumat cubs’ stomach contents offered a unique glimpse into the ecosystem of Late Pleistocene Siberia. Woolly rhinoceroses, mammoths, and reindeer roamed the tundra-steppe, and wolves were among the top predators.

Chemical “fingerprints” found in the cubs’ bones, teeth, and tissue revealed that they ate both meat and vegetation, much like wolves today. This mixed diet reflects an opportunistic survival strategy — feeding on whatever the harsh Ice Age environment provided.

The cubs’ last meal of rhinoceros meat was likely brought to them by their pack, possibly after adults hunted or scavenged the carcass. The undigested rhino hide found in one cub suggests they died soon after eating, freezing so quickly that their stomach contents were preserved.

Ancient Wolves and Dog Domestication

This discovery highlights how difficult it is to trace the origins of dog domestication.

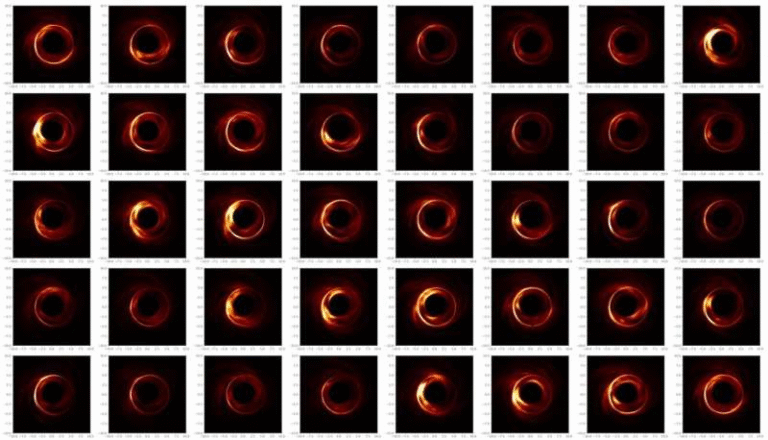

Scientists know that gray wolves have existed for hundreds of thousands of years, and that dogs descended from some wolf populations — but not from all of them. The genetic evidence from the Tumat wolves shows that they belonged to a lineage that eventually died out, meaning they didn’t contribute to modern dog ancestry.

This complicates the timeline of domestication. The earliest confirmed dog remains date to around 15,000–20,000 years ago, but the process might have started earlier, possibly with multiple wolf populations being tamed in different regions.

What’s clear is that the Tumat Wolves were not part of that early domestication process. Instead, they represent a wild wolf population that lived parallel to early humans — sometimes near them, but not yet under human control.

How Ancient DNA Sheds Light on Prehistoric Life

The preservation of the Tumat cubs was so remarkable that scientists could extract DNA, proteins, and chemical residues not just from bone, but from soft tissue and even gut contents.

These biological samples allow researchers to reconstruct details about diet, health, environment, and genetics — data that skeletal remains alone can’t provide.

The analysis also compared isotopic signatures (ratios of carbon and nitrogen) from the cubs’ tissues to known values from ancient prey species. This confirmed that they fed mainly on herbivores like woolly rhinoceros and reindeer, while also consuming plants and possibly small animals like birds.

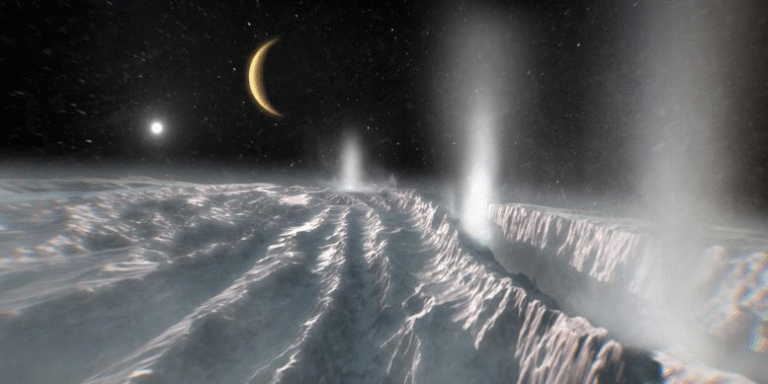

The Siberian Setting: A Window Into the Ice Age

Around 14,000 years ago, the landscape of northern Siberia was transitioning from the Last Glacial Maximum into a slightly warmer period.

The region around Tumat would have been a tundra-steppe environment — open grassland interspersed with shrubs and river valleys. Large herbivores like mammoths, woolly rhinos, horses, and bison grazed across these plains, providing food for predators such as wolves and cave lions.

Humans were also present in the region, hunting large mammals and leaving traces of their activity, such as burned bones and stone tools. However, despite living in proximity, humans and wolves remained separate species with distinct survival strategies.

What Makes This Discovery Special

The Tumat wolves stand out not just for their age, but for their state of preservation. Soft tissues rarely survive for thousands of years, yet in this case, the permafrost acted as a perfect natural freezer.

Researchers could study their fur, internal organs, teeth, and even whiskers. This level of detail offers an unprecedented look at an extinct wolf population and helps bridge the gap between paleontology and modern biology.

Their discovery also shows the potential of ancient permafrost finds to reveal details about Ice Age ecosystems — from diet and climate to the evolution of animal species that shaped the world long before humans dominated it.

What This Means for the Future of Research

Although these wolves didn’t lead directly to domestic dogs, they’ve opened up new avenues for studying the evolutionary relationship between wolves, humans, and dogs.

Understanding how different wolf populations lived and adapted can help scientists piece together where and how domestication truly began — a question that remains unresolved despite decades of research.

More discoveries like the Tumat wolves could one day pinpoint the specific region and timeframe where the first human-wolf partnerships emerged, leading to the loyal companions we know today.

Final Thoughts

The “Tumat Puppies” have turned out to be wolves frozen in time, not dogs. But in many ways, that makes their story even more fascinating. They give us a clear snapshot of what life looked like in the Siberian Ice Age — the diet, environment, and behavior of wild wolves living side by side with early humans.

Their discovery also reminds us that evolution and domestication are rarely simple or linear. The black fur that once hinted at dog ancestry now tells a different story — one of adaptation, diversity, and survival.

As researchers continue to uncover secrets buried in the ice, each new finding helps us better understand where we came from — and who we once shared the planet with.

Research Reference:

“Multifaceted analysis reveals diet and kinship of Late Pleistocene ‘Tumat Puppies’” – Quaternary Research (2025)