Virtual Reality Makes Climate Change Feel Real — Stanford Study Shows It Can Reduce Indifference

A new Stanford University study has found that virtual reality (VR) can make people care more about climate change by helping them emotionally connect with distant communities affected by it. The research, published in Scientific Reports in October 2025, reveals that when people use VR to experience faraway locations impacted by climate-related events, they feel closer to those places and more concerned about what’s happening there.

This work was led by Monique Santoso, a Ph.D. student at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, along with Jeremy Bailenson, director of Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab (VHIL), and co-authors Portia Wang and Eugy Han.

The Study Design and Who Took Part

The researchers recruited 163 Stanford students for the experiment. Each participant was randomly assigned to experience one of nine locations across the United States, including New York City, Miami, Des Moines, and Massachusetts’ North Shore.

Participants were divided into two groups: one group experienced these places in virtual reality, while the other viewed static images of the same locations. During their session, participants listened to a short news story describing climate change-driven flooding affecting that area.

While VR participants flew through a realistic 3D environment using low-cost consumer software—similar to Google Earth VR or Fly—others simply saw flat images on a screen. After the experience, both groups answered detailed surveys about their feelings, perceptions of risk, and connection to the place they had just seen.

What the Researchers Found

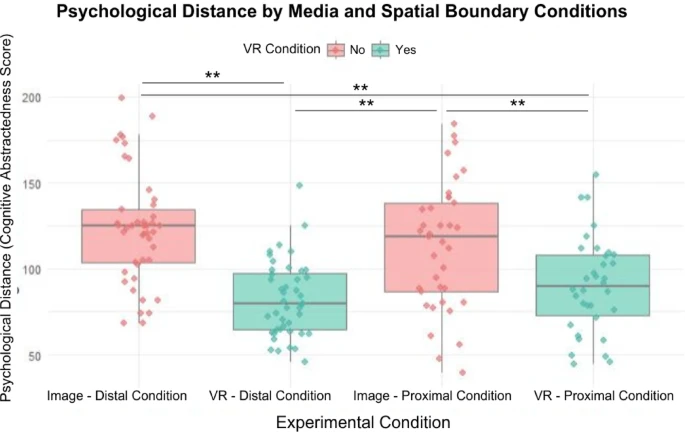

The results were striking. People who experienced the locations through VR:

- Felt the distant locations were psychologically closer.

- Reported less indifference toward climate impacts.

- Expressed more frustration—a constructive emotion linked to motivation to act.

- Had higher risk perception, meaning they saw climate change as a more serious threat.

- Wrote longer and more emotionally engaged stories when asked to describe the experiences of people living in those areas.

In contrast, participants who only saw static images showed far weaker responses.

Interestingly, VR didn’t make participants feel hopeless or fearful. Instead, it seemed to generate productive concern—the kind that drives people to think, care, and possibly act.

The researchers also found that political ideology influenced emotional reactions. Liberals and conservatives both showed increased engagement when using VR, but the intensity and type of emotions varied. Despite ideological differences, all participants developed stronger attachment to the locations they “visited.”

Why Virtual Reality Works

According to the study, the power of VR lies in how it reduces what psychologists call “psychological distance.” Climate change often feels remote—something that happens “elsewhere” or “later.” When people experience a problem firsthand, even virtually, their minds treat it as closer and more relevant.

This sense of proximity makes it harder to dismiss environmental problems as someone else’s issue. By “traveling” to places hit by floods or rising seas, users begin to see these communities as connected to their own lives.

The researchers highlight that VR helps people form emotional bonds or “place attachment.” In other words, when someone virtually visits a distant city and sees the effects of climate change there, they develop empathy and a sense of responsibility toward it.

How This Differs from Typical Climate Communication

Traditional climate communication often relies on fear-based messages—showing disasters, destruction, and alarming statistics. While such approaches can grab attention, they also risk causing emotional overload and paralysis, making people tune out.

The Stanford team took a different path. Rather than using VR to show catastrophic future scenarios, they focused on exploration and connection. The simple act of visiting and learning about a place in VR was enough to increase caring and awareness.

This suggests that positive engagement—helping people feel connected to the world rather than terrified of it—may be a more effective strategy for inspiring climate action.

The Broader Implications

The study’s implications go beyond academic curiosity. As VR headsets and immersive software become cheaper and more accessible, this technology could become a powerful communication tool for environmental education, journalism, and advocacy.

Teachers could use VR to take students on virtual field trips to melting glaciers or flooded coastlines. Newsrooms could add immersive features to climate stories, letting viewers “walk” through affected communities. Nonprofits could use VR experiences to show donors where their money makes a difference.

Perhaps most importantly, this study suggests VR can bridge partisan divides. By focusing on shared human experiences and emotions rather than abstract political debates, it may help people with different worldviews find common ground in caring for the planet.

Limitations and Next Steps

Like all research, this study has its limits. The participants were university students, a group that may not represent the general population. The research also focused on U.S. locations, so it’s unclear whether similar effects would occur in other countries or cultures.

The team recommends that future studies explore cross-cultural applications, such as showing people in the United States VR scenes from communities in Southeast Asia or Africa that are already dealing with rising sea levels and drought.

Another open question is how long the effects last. The study measured emotions and perceptions shortly after the VR session, but it didn’t test whether those feelings lead to long-term behavioral changes, such as supporting environmental policies or making lifestyle adjustments.

Still, the authors believe this is a promising start. The experiment shows that even short, inexpensive VR experiences—using off-the-shelf software—can meaningfully shift people’s perceptions about climate change.

Understanding Psychological Distance and Climate Engagement

To better understand why this matters, it helps to know what psychological distance means. The term comes from construal level theory, which explains that the farther away something feels—whether in time, space, or similarity—the more abstract and less emotionally engaging it becomes.

When it comes to climate change, people often perceive it as distant in all four dimensions:

- Spatially distant (it’s happening somewhere else)

- Temporally distant (it’s a future problem)

- Socially distant (it affects other people, not me)

- Hypothetically distant (I’m not sure it’s real or urgent)

By using VR to let people see and experience these places directly, the Stanford study effectively reduces spatial and social distance. That psychological shift makes the issue feel present, real, and personal.

VR and Environmental Education

Virtual reality is already being used in environmental education around the world. For example, projects like “This Is Climate Change” and “Tree” place users inside simulated environments where they can observe the impact of deforestation, wildfires, or rising temperatures firsthand.

These experiences are not about passive learning—they are about immersion and empathy. The Stanford study adds scientific evidence that this kind of immersive exposure can genuinely influence emotions and thought patterns, even without fear-based storytelling.

As technology continues to evolve, we can expect VR to become an essential tool for climate literacy, especially for younger generations who are already comfortable with interactive media.

A Step Toward Making Climate Change Personal

Climate change is one of the biggest collective challenges humanity faces, yet it often feels distant and abstract. This new study from Stanford suggests a simple but powerful insight: when people feel connected to the world, they care for it more.

By using virtual reality not just for entertainment but for understanding, we can help people everywhere feel that the planet’s problems are their problems too—and maybe even inspire them to act.

Research Reference:

Virtual Reality Reduces Climate Indifference by Making Distant Locations Feel Psychologically Close — Scientific Reports (2025)