Proper Processing of Recycled Manure Solids Can Greatly Reduce Pathogen Risks in Dairy Farm Bedding

Dairy farmers across the Midwest are increasingly turning to recycled manure solids (RMS) as bedding for their cows. The idea sounds odd at first—using manure as bedding—but it’s a growing practice that helps farms cut costs, recycle waste, and support sustainable operations. However, manure naturally contains bacteria, including those that cause mastitis and other diseases. This has raised an important question: how can farmers make RMS bedding safe for cows without sacrificing its benefits?

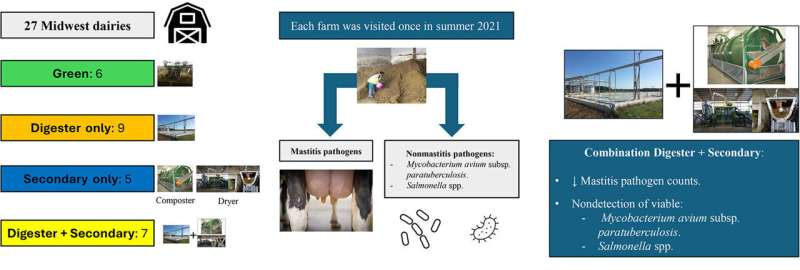

A recent study published in JDS Communications (2025) answers that question with new, detailed data. Researchers found that the way manure solids are processed makes a huge difference in how many pathogens survive in the final bedding product. The research, conducted on 27 dairy farms across Minnesota and Wisconsin, explored several methods of preparing RMS and revealed which systems are most effective at keeping harmful microbes under control.

Why Recycled Manure Solids Are Becoming Popular

Before diving into the findings, it’s worth understanding why RMS has gained traction in modern dairy farming. Bedding choice affects cow comfort, udder health, and milk quality. Common bedding materials—like sand, straw, and sawdust—are becoming more expensive or harder to source consistently. RMS, on the other hand, is readily available on every dairy farm, inexpensive, and promotes circular waste management, where waste from cows is reused within the farm ecosystem.

RMS is created by separating liquid and solid components from manure slurry. The solids are then dried or treated and reused as bedding material. It’s soft, absorbent, and environmentally friendly. However, because it originates from manure, it can harbor bacteria like E. coli, Klebsiella, Salmonella, and Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP)—the bacteria that causes Johne’s disease in cattle.

The challenge is finding a way to reduce bacterial contamination while keeping the bedding cost-effective and sustainable.

How the Study Was Conducted

The new study, led by researchers Felipe Peña-Mosca of Cornell University and Sandra Godden of the University of Minnesota, examined how different RMS processing methods affect both mastitis-causing pathogens and other harmful bacteria. The team looked at 27 dairy farms across Minnesota and Wisconsin that used various RMS preparation systems. These systems were grouped into four categories:

- Raw or Green Solids (GRN): Minimal processing. Solids are separated and used directly without further treatment.

- Digester-Only (DIG): Solids undergo anaerobic digestion, where microbes break down organic material in oxygen-free conditions, generating biogas and heat.

- Secondary Processing Only (SEC): Involves composting or hot-air drying of solids without anaerobic digestion.

- Digester Plus Secondary Processing (DIG+SEC): A combination of anaerobic digestion followed by composting or drying.

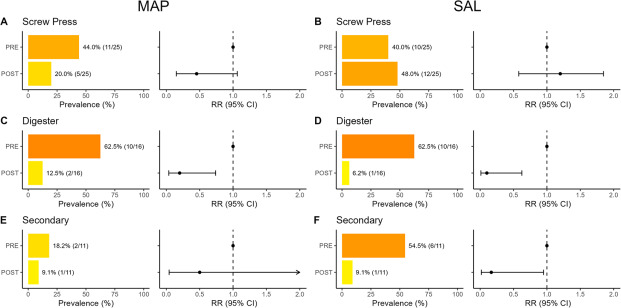

Researchers collected slurry and bedding samples before and after each processing step. They tested for the presence of mastitis pathogens and nonmastitis pathogens, including Salmonella spp., Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis (MAP), and Campylobacter jejuni.

What the Study Found

The results were eye-opening. Pathogen levels varied dramatically depending on how the manure solids were treated.

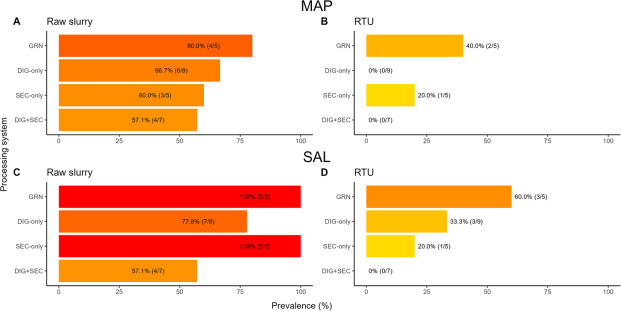

- Farms using raw or green solids (GRN) had the highest levels of bacteria. Both mastitis-causing and nonmastitis pathogens were found in these samples.

- The single-step systems—either digestion alone or secondary processing alone—reduced bacterial counts compared to raw solids. However, even after treatment, pathogens were still detectable in the bedding.

- The most effective system was the combined digester-plus-secondary process (DIG+SEC). This two-step treatment produced bedding with much lower counts of mastitis pathogens and, importantly, no detectable Salmonella spp. or MAP in the ready-to-use bedding samples.

- Interestingly, Campylobacter jejuni was not detected in any of the final bedding samples across all systems.

To put numbers on it: MAP was found in about 68% of raw slurry samples, and Salmonella spp. in roughly 80%, but both were undetectable in bedding processed through the DIG+SEC systems. This finding is a strong indicator that multi-step treatment drastically lowers bacterial risks.

Why Anaerobic Digestion and Composting Work Better Together

So, why does combining a digester with composting or drying work best?

Anaerobic digestion breaks down organic matter under heat and microbial action, which can significantly reduce pathogen populations. Composting or hot-air drying then adds a second phase of pathogen kill, thanks to higher temperatures and drying effects. When these two processes are used in sequence, very few bacteria can survive.

This layered approach makes sense from both a biological and engineering standpoint. Digestion disrupts microbial communities and creates conditions that pathogens struggle to adapt to, while composting completes the job by destroying residual organisms and reducing moisture—a key factor that bacteria need to thrive.

What This Means for Dairy Farmers

For dairy producers, this research offers clear, actionable guidance. If you’re using RMS bedding—or considering it—how you process the manure solids matters more than almost anything else. The combination of anaerobic digestion followed by a secondary process (like composting or drying) provides the safest bedding option among the systems studied.

The study also reinforces the importance of consistent processing practices. Even small differences in temperature, retention time, or drying can affect the final bacterial load. Farmers may need to balance the costs of extra equipment or time against the benefits of improved udder health and reduced disease transmission.

It’s worth noting that this was an observational study conducted only during summer months, so results may vary in colder seasons or under different environmental conditions. More research is needed to confirm how well these results hold year-round and across larger or smaller farms.

Broader Implications: Sustainability and Animal Health

The study goes beyond pathogen control—it ties into the larger conversation about sustainable dairy farming. Using RMS bedding supports circular farming systems, where waste is reused rather than disposed of. This reduces the need for external materials like sand and minimizes manure management challenges.

From an animal welfare perspective, RMS bedding is often softer and more comfortable than inorganic alternatives. Cows tend to lie down more frequently, a sign of better comfort, which can improve milk yield and reduce stress. However, comfort alone isn’t enough—the bedding also needs to be hygienically safe. This study helps bridge that gap by showing which treatments make RMS safer for everyday use.

The Bigger Picture: Balancing Cost, Comfort, and Cleanliness

One of the challenges with RMS is balancing economics and hygiene. Processing systems like digesters and composting setups require capital investment and ongoing maintenance. Smaller farms may find it difficult to justify the costs unless they can see measurable benefits in cow health and milk quality.

Yet, the data are promising. By controlling pathogens through proper processing, farms can potentially reduce mastitis rates, lower veterinary costs, and improve milk hygiene, all of which translate into better profitability in the long run. Moreover, RMS use can reduce dependence on mined sand and other finite resources, aligning with the environmental goals many farms now pursue.

What’s Next for RMS Research

The authors note that the next steps include studying how pathogen levels vary across different seasons, how farm size and herd management affect results, and whether economic analyses can pinpoint the most cost-effective systems for various farm types. This information will help refine best practices for safe and sustainable RMS use.

In short, this study provides a scientific foundation for a practical question that many dairy producers face: How do you make manure-based bedding both safe and sustainable? The answer, for now, seems clear—proper, multi-step processing is the key.