Tufts Researchers Reveal Stark Racial and Social Inequities Around America’s Superfund Toxic Sites

A new study by researchers at Tufts University has shed light on how racial and social disparities shape who lives near America’s most dangerous toxic waste sites—and who benefits the least from cleanup efforts. Published in Nature Communications in October 2025, the study exposes a troubling imbalance in how contamination affects communities across the United States, especially those that are historically underserved or socially vulnerable.

Understanding Superfund Sites

Superfund sites are areas in the U.S. contaminated by hazardous waste and designated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for cleanup because they pose serious risks to human health and the environment. These sites can include everything from abandoned factories and mining operations to landfills and old chemical plants.

The EPA uses a Hazard Ranking System (HRS) to score each site based on various risk factors—such as toxicity levels, likelihood of contaminant release, and potential exposure routes through groundwater, soil, or air. Any site scoring above 28.5 qualifies for inclusion on the National Priorities List (NPL), which determines which locations receive federal funding for remediation.

However, that 28.5 threshold was originally set in the 1980s merely to cap the first list at 400 sites—and it has never been updated. This outdated benchmark means that thousands of contaminated locations remain off the list, often receiving little or no cleanup support. The new study analyzed over 11,600 of these unlisted sites, finding that they continue to endanger nearby communities.

What the Study Found

The Tufts research team—led by Farshid Vahedifard, professor and Louis Berger Chair in Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Ph.D. student Mohammed Azhar—collaborated with scientists from the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, Mississippi State University, and George Mason University.

Credit – Nature

Their findings are both alarming and eye-opening. Around 80% of the U.S. population lives within just 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) of at least one Superfund site. Even more concerning, nearly 60% of those people live near sites where no cleanup is currently underway—or where cleanup efforts have stalled or fallen short.

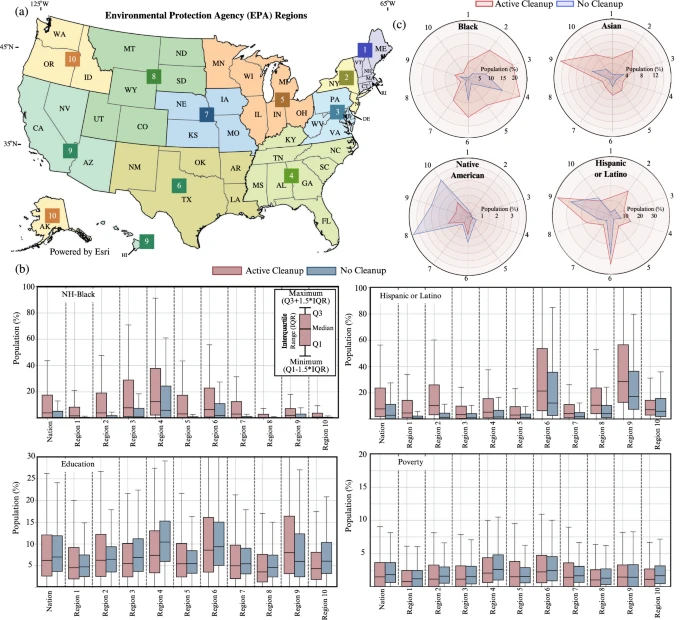

The study also reveals that Black, Asian, and other minority populations are disproportionately exposed to these hazardous zones. Nationally, Black populations are 100% more likely, and Asian populations are 200% more likely, to live near Superfund sites compared to communities that are unexposed.

State-by-State Disparities

At the state level, the inequalities become even more pronounced.

- In Massachusetts, Asian residents living near contaminated areas are 11 times higher in proportion compared to those in cleaner neighborhoods.

- In New Jersey, the figure is 10 times higher, and in New York, it’s about 8 times higher.

- Black populations also face steep disparities: they are 10 times more likely to live near contaminated sites in Massachusetts, and 7 times more likely in Connecticut and Nebraska.

The disparities are particularly severe for communities located near sites that aren’t on the National Priority List, meaning no active cleanup has been initiated. In New England, for example, Black populations near these neglected sites are 13.7 times higher than in unexposed communities, while Hispanic populations are 9.6 times higher.

The New Tool for Equitable Cleanup

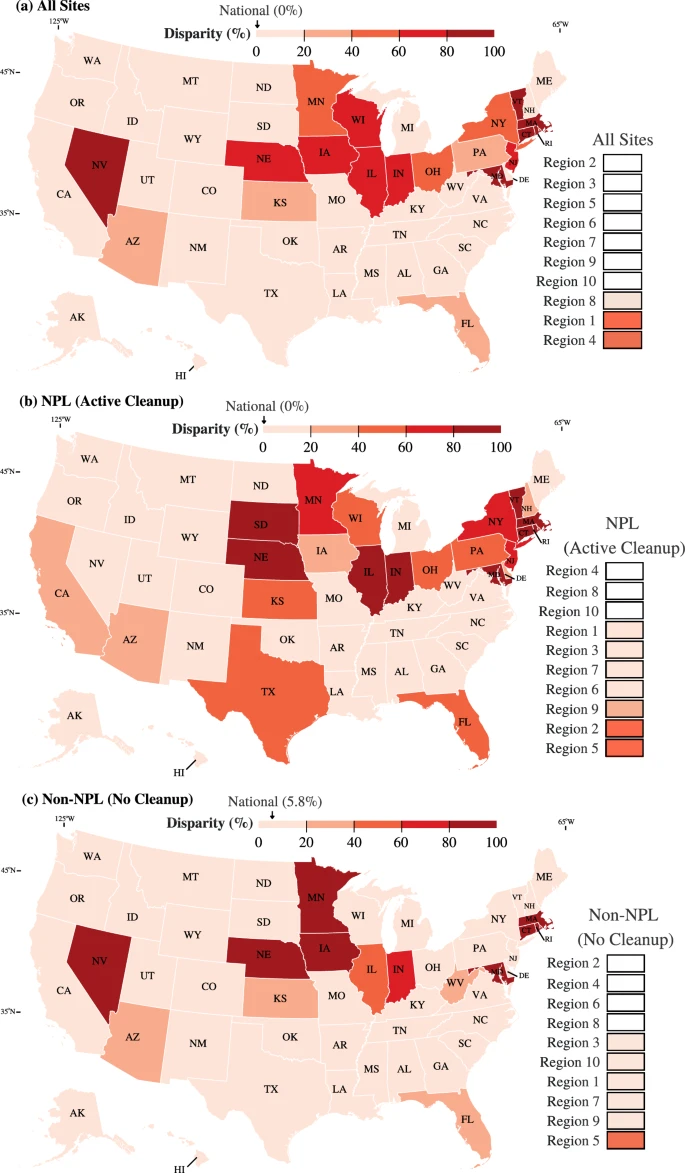

Recognizing that traditional risk scoring doesn’t account for social vulnerability, the Tufts team developed a new framework called the Action Priority Matrix (APM).

The APM works by combining two measures:

- A Superfund Exposure Score (SES) — showing how much of a region’s population is exposed to toxic sites.

- A Disparity Percentage — indicating how much minority or disadvantaged groups are overrepresented in those exposed populations.

By plotting these two values against each other, the matrix divides sites into four quadrants—each representing different levels of urgency for action. The most critical quadrant highlights areas with both high exposure and high disparity, marking them as top priorities for cleanup and funding.

Using this model, the study identified seven states with the highest combined exposure and disparity levels: Nevada, Maryland, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, New Jersey, and New York. These states, according to the researchers, should be prioritized for future Superfund cleanup efforts.

Why the Disparities Exist

The researchers link much of the unequal exposure to historical and structural factors, such as redlining, discriminatory zoning laws, and segregation practices that forced minority and low-income families to live in more industrialized or less desirable areas. Over time, these same areas became dumping grounds for waste and pollution.

Economic constraints also play a role. Vulnerable groups often lack the financial means to move away from contaminated neighborhoods. And without strong political representation, they have limited influence in shaping environmental policies or pressing for stricter enforcement.

Interestingly, the current Hazard Ranking System doesn’t consider these demographic realities. It evaluates the chemical and environmental risks, but not the social vulnerability of the people living nearby. As a result, some sites that technically fall below the HRS threshold might still deserve immediate attention when viewed through an equity lens.

The researchers suggest that by integrating the APM framework with existing HRS assessments, policymakers could ensure that communities facing both high risk and high disadvantage receive the cleanup attention they need.

A Nationwide Challenge

There are currently over 13,000 identified Superfund sites across the United States. While many of the most hazardous ones are listed under the National Priorities List and receive federal funding, thousands remain in limbo—posing continuing threats to local residents.

These sites can contain pollutants such as lead, arsenic, mercury, benzene, dioxins, and other carcinogenic or neurotoxic compounds. Contamination often spreads through groundwater, air, or soil, affecting crops, livestock, and drinking water sources.

The EPA reports that living near Superfund sites has been linked to increased risks of cancer, respiratory disease, developmental issues, and reproductive health problems. The Tufts study reinforces that these health burdens are not evenly distributed across populations.

Why It Matters Beyond Superfund Sites

The study’s authors emphasize that the Action Priority Matrix isn’t just useful for toxic waste management—it could also serve as a framework for tackling other environmental justice challenges. For example, it could guide equitable strategies in climate adaptation, disaster resilience, or infrastructure development to ensure vulnerable groups aren’t left behind.

By combining demographic data with environmental risk indicators, agencies could make more informed decisions about where to direct resources. It’s a call for a data-driven approach to fairness—making sure that environmental cleanup and protection efforts don’t just look at pollution levels, but also at who’s most affected.

A Push for Change

The Tufts researchers hope their findings encourage policymakers and agencies like the EPA to rethink how Superfund sites are prioritized. Updating the decades-old HRS score and integrating demographic data could make the system more equitable and responsive to real community needs.

The message is simple but powerful: no community should be left behind in the fight against environmental contamination. And as the study reveals, addressing pollution isn’t just about science and engineering—it’s about justice.

Research Reference:

Equitable cleanup of Superfund sites leaving no U.S. community behind – Nature Communications (2025)