Spotted Lanternflies Use a Toxic Shield from Tree of Heaven to Repel Hungry Birds

A new study from researchers at Penn State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences has revealed that the invasive spotted lanternfly may use toxins from its favorite host plant, the tree of heaven, to make itself taste bad to birds. This fascinating defense mechanism could explain why some birds are hesitant to eat the pest, despite its growing abundance across the eastern United States.

The findings, published in the Journal of Chemical Ecology in October 2025, were led by postdoctoral researcher Anne Johnson under the supervision of Professor Kelli Hoover. Their team set out to understand whether birds could help control lanternfly populations or if the insects had found a way to protect themselves using the plants they feed on.

How the Researchers Tested the “Toxic Shield” Theory

The spotted lanternfly, or Lycorma delicatula, is a sap-feeding insect originally from Asia that has become a serious agricultural pest in North America. It damages vineyards, orchards, and tree nurseries, feeding on more than 70 plant species. However, it has a particular fondness for Ailanthus altissima, commonly called the tree of heaven—another invasive species from the same region of Asia.

Researchers suspected that the lanternfly might be borrowing chemical defenses from this plant. The tree of heaven produces a group of bitter compounds called quassinoids, which are toxic to many animals. These chemicals give the plant a strong, unpleasant taste and smell.

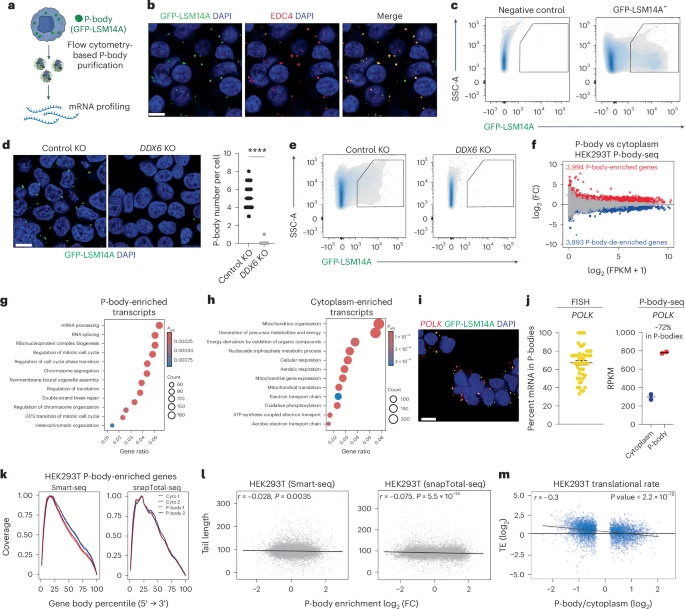

To test this, Johnson and her team reared spotted lanternflies in controlled environments, giving some access to tree of heaven leaves while keeping others on alternative host plants such as walnut, willow, or silver maple. They then examined the lanternflies at various life stages—from eggs to adults—to see if the insects had stored any of the plant’s toxins.

Confirming the Presence of Quassinoids

Chemical analysis confirmed that lanternflies feeding on tree of heaven absorbed and stored quassinoids in their bodies. The researchers detected compounds like ailanthone, glaucarubinone, 2’-acetylglaucarubinone, 13,18-dehydroglaucarubinone, and grandilactone A—all known toxins from the tree of heaven.

The highest concentrations of these chemicals were found in the salivary glands of the insects, with smaller amounts in other body parts. Adult lanternflies that had fed on tree of heaven contained more than six times the concentration of quassinoids compared to those raised on other plants.

Interestingly, the toxins weren’t just limited to adult lanternflies. The team also detected quassinoids in the eggs, suggesting that female lanternflies pass these toxins to their offspring. This finding indicates that the insects may be protecting their next generation before it even hatches.

Bird Feeding Experiments

The researchers then moved on to see how birds reacted to these chemically armed insects. They conducted two sets of experiments: one involving nesting house wrens (Troglodytes aedon) and another using wild bird feeders filled with suet cakes.

For the first experiment, the team offered freeze-killed lanternfly nymphs—some that had fed on tree of heaven and some that hadn’t—to nesting wrens. The results were clear: the birds ate far more of the nymphs that had not been exposed to the toxic plant. When feeding their chicks, the wrens were even more selective, often choosing only the toxin-free lanternflies.

In the second experiment, adult lanternflies from both groups were ground up and mixed into separate batches of suet cakes. These were placed in bird feeders visited by several species, including woodpeckers, black-capped chickadees, white-breasted nuthatches, and Carolina wrens. Cameras recorded how often each type of suet was pecked.

Once again, the pattern was consistent: birds preferred suet containing lanternflies that had not fed on tree of heaven. In other words, the presence of quassinoids appeared to make the insects less appetizing.

Why the “Toxic Shield” Works

The study supports the idea that the spotted lanternfly uses a “toxic shield”—a defense mechanism borrowed from its host plant. By feeding on tree of heaven, the insect essentially seasons itself with distasteful chemicals, discouraging predators like birds.

The researchers note that while birds still occasionally eat the toxic lanternflies, they clearly prefer the less-defended ones. This means the defense isn’t perfect, but it may be enough to reduce the risk of predation.

In nature, even a small chemical advantage can make a difference. Many animals—from monarch butterflies that store milkweed toxins to ladybugs that accumulate plant alkaloids—use similar strategies to make themselves unappealing to predators. The spotted lanternfly now appears to belong in that same category.

What This Means for Pest Control

While some birds clearly do eat lanternflies, their effectiveness in controlling populations may be limited. The researchers emphasize that the extent to which birds help reduce lanternfly numbers “remains up in the air.”

If lanternflies feeding on tree of heaven are less likely to be eaten, the abundance of this invasive plant could be indirectly protecting the insect. That raises an intriguing idea: removing or managing tree of heaven stands might not only reduce a key food source but also make lanternflies more vulnerable to predators.

This line of thinking could inform future management strategies. Since birds and other natural predators are part of the ecosystem, understanding how chemical defenses affect their feeding behavior could help shape integrated pest control efforts.

Other Predators and Broader Implications

The spotted lanternfly isn’t just targeted by birds—other predators, such as insects, also feed on it. However, the research team has previously found that insect predators are less affected by whether the lanternfly has fed on tree of heaven. In other words, these toxins don’t seem to deter all predators equally.

This discovery highlights how complex ecological interactions can be. A defense that works against birds might not work against spiders, mantises, or beetles. Understanding which predators are effective and under what conditions is key to developing sustainable management strategies.

A Quick Look at the Tree of Heaven

The tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is an invasive tree introduced to North America in the late 1700s from China. It’s notorious for spreading quickly, producing thousands of seeds, and growing even in poor soils and urban areas.

Its chemical defenses—especially the quassinoids—are so potent that they suppress the growth of nearby plants, giving it a competitive edge. Unfortunately, these same compounds now seem to be helping the spotted lanternfly survive in areas where it’s not native.

This symbiotic relationship between two invasive species—one plant and one insect—makes management even more challenging. Removing the tree of heaven could potentially weaken the lanternfly’s defenses, but it’s easier said than done, as the tree spreads rapidly and resprouts after cutting.

The Spotted Lanternfly’s Ongoing Invasion

Since its first detection in Pennsylvania in 2014, the spotted lanternfly has spread to more than a dozen U.S. states, including New Jersey, New York, Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio. The pest causes millions of dollars in crop losses, especially in vineyards, where it feeds on grapevines and reduces yield.

Its colorful wings and jumping behavior make it easy to spot, but also deceptively harmless-looking. Behind the striking appearance lies a serious economic threat—and now, a clever natural defense.

Understanding how these insects interact with predators and plants could be key to managing their populations. If removing tree of heaven can reduce their chemical armor, that may offer a practical approach alongside traditional control methods like sticky traps, insecticides, and egg mass scraping.

Final Thoughts

The Penn State team’s findings add a new layer to our understanding of invasive species dynamics. The spotted lanternfly doesn’t just rely on numbers—it relies on chemistry. By co-opting the toxins of its favorite host plant, it’s managed to make itself less appealing to at least some of its natural enemies.

While that’s bad news for farmers and gardeners hoping that birds might control the pest naturally, it’s a valuable insight for researchers. It shows how ecological relationships—between plants, insects, and predators—shape the success of invasive species in their new environments.

As scientists continue to explore these interactions, one thing is clear: solving the lanternfly problem will require more than just removing insects. It will require understanding the chemical connections that make this pest so resilient.

Research Reference: Sequestration of plant defenses by spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) and effects on avian predators – Journal of Chemical Ecology (2025)