A Day In The Life Of A Library Book

If you’ve worked in or around libraries, you already know a book isn’t just a book. But when I started digging into what actually happens in a day of its life, I realized just how layered and invisible that workflow really is.

A single book might interact with an ILS, a consortial catalog, RFID tracking, hold queues, and even a preservation review team—all in 24 hours. Wild.

This post isn’t just another “here’s how a book gets borrowed” explainer. I wanted to map out what happens behind the scenes, not just at the service desk. So I’m walking you through the operational life of a library book—from the moment it enters the system to what happens when it doesn’t circulate at all.

And if you’ve ever tried to trace one through Alma or Sierra, you know: the magic’s in the metadata.

Pre-Circulation Touchpoints – The Book Before You Meet It

Before a book ever hits the shelf, it’s already been through a whole journey—and that journey quietly defines everything that comes after. What blew my mind is how a book’s lifecycle is less about the object, and more about the data architecture behind it.

Let’s unpack what happens before you or I ever get to borrow it.

Acquisition Isn’t Just Buying Books

I always thought acquisitions was just, “Hey, let’s order this title,” but the reality is way more nuanced. Libraries often order through systems like GOBI, leveraging approval plans or firm orders that sync with collection development profiles.

The metadata starts here—vendor records are loaded into the ILS (sometimes even before the item arrives), and those records are rarely clean. One librarian told me, “You always have to clean vendor records—every time.”

If not corrected, those small errors ripple across catalogs and discovery layers later on.

Cataloging Is Where Identity Gets Locked In

This part is honestly fascinating.

The cataloger decides how this book will exist in the library’s universe.

Original cataloging vs. copy cataloging changes everything. Is it going to follow RDA?

Do you modify OCLC records or create a new one?

Those decisions impact discoverability and interoperability with other systems like WorldCat or shared consortia platforms.

And don’t get me started on local fields. I saw one institution use a 945 tag just to denote “shelf display rotation”—super specific, but so smart for internal tracking.

Physical Processing Is Where Tech Meets Tactile

Here’s where digital meets physical: barcode placement (is it top left or bottom right?), spine label consistency, RFID encoding, even cover lamination.

These aren’t just aesthetic or procedural decisions—they’re tied directly to how items are tracked and preserved.

RFID, for example, isn’t just for security; it enables auto-check-in via AMH (automated materials handling).

So if the RFID isn’t encoded right, the entire check-in logic fails. One tech services team told me they audit 10% of new items just to catch RFID misfires.

Shelving Is More Than Just Alphabetizing

Whether you’re in a Dewey or LC library, shelving is a metadata outcome. Location codes in the ILS have to match the call number structure; otherwise, your book gets lost even before it circulates.

And some collections, like oversize or zine archives, totally break the usual logic—so exceptions get built into workflows.

I spoke to someone who runs a special collection where shelving location alone triggers different climate controls. That’s not shelving—that’s infrastructure.

The Final Layer of Pre-Circulation is Inventory

Once it’s shelved, that book becomes “findable”—but only if the system knows it’s really there. Libraries use shelf-reading apps or RFID sweeps to reconcile the ILS with physical reality.

Without it?

You’ve got phantom items: they exist in the catalog, but no one can find them.

And just like that, the book’s ready. But trust me—its day’s just getting started.

The Operational Life Cycle of a Book, a.k.a Circulation Day

Once that book hits the open stacks, the real-time choreography begins—and it’s honestly kind of mesmerizing.

This part of a book’s life is heavily automated but still full of human touchpoints, and every move it makes has a digital echo somewhere in your ILS.

What I didn’t realize at first was how tightly controlled each status shift is—and how much policy lives behind what seems like a simple “check-out.”

Let’s walk through a day in the life of one book—let’s say The Left Hand of Darkness—and follow what happens to it once a patron decides to check it out.

1. Morning Checkout: A Trigger Chain Begins

A patron walks up, scans their card, and boom—the system kicks off a rule-based chain reaction. The ILS (say, Polaris or Alma) looks up the patron type (student, faculty, public user), their borrowing privileges, and any fines or holds on their account.

Once cleared, the book is scanned and its status flips from “Available” to “Checked Out”, immediately syncing across OPAC, consortial layers (like SHARE or MOBIUS), and discovery platforms like Primo or EBSCO.

Behind that simple scan, so much is happening:

- A due date is calculated—maybe 3 weeks for undergrads, a semester for faculty.

- The loan is logged in the user’s history (unless anonymization is turned on for privacy).

- The system starts a soft countdown for overdue fees, renewal prompts, or automated courtesy emails.

I didn’t realize just how granular the rules could be until I saw a config file with over 40 patron-type-specific loan policies. It’s not just “three weeks”—it’s “three weeks unless it’s a DVD, or a 14-day loan collection, or the patron is on academic probation.”

2. Transit: When a Book Disappears from the Building

Once that book leaves the building, it becomes invisible in a physical sense—but the system still tracks it. RFID gates at exits log movement data (mostly for internal analytics and loss prevention), and some systems even ping staff if high-risk or in-demand items are leaving during flagged hours.

But most importantly, that book stops being part of the accessible shelf inventory, which means users browsing the catalog see it as “Checked Out.” In a high-turnover collection, this can immediately impact collection development decisions.

One librarian I spoke to said they run daily reports to see which titles have been off the shelves more than 80% of the time—those are instant candidates for duplicate orders.

3. Return: A Mini System Reboot

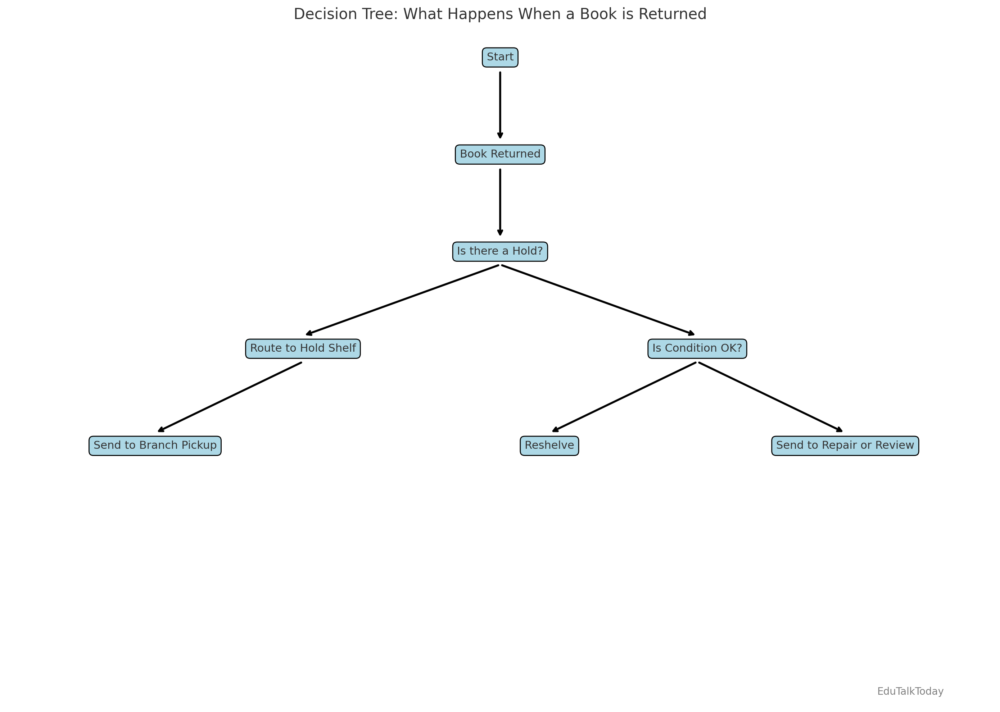

Return might look simple from the outside—you drop a book in the bin—but it’s a carefully controlled reintegration. If the library uses an AMH (Automated Materials Handling) system, RFID or barcode is scanned automatically, and the book’s status flips back to “In Library.” At this point:

- Any pending hold request on that item is checked.

- If someone requested it while it was out, the system routes it to the holdshelf, and a notification gets sent.

- If not, it’s re-shelved or possibly flagged for routing to another branch, display, or processing station (like for damage review).

Some libraries even run conditional scripts—if a book has been checked out more than 50 times, it gets flagged for condition review before going back on shelf.

One tech services manager told me they scan for “high velocity” items—books that never seem to sit still. Those titles often bypass standard reshelving and go directly to a rapid return shelf near the front desk for higher visibility and faster turnover.

4. Hold Processing & Routing: Invisible Logistics

If the book was requested, things get interesting. Hold queues vary in complexity. Some libraries allow patrons to pick up holds anywhere across a district or campus, which means the book needs to be routed across a logistics network, like a mini UPS for books.

Every step—from “In Transit” to “On Hold Shelf”—is logged in the ILS. This lets patrons track their request status in real time and helps staff troubleshoot routing issues. Some systems use color-coded slips or embedded RFID task codes to make sorting smoother. In some branches, a single item may hit 4 or 5 ILS status changes within an hour just to get to the right shelf.

5. The Not-So-Silent Audit Trail

Even after the book’s been returned and re-shelved, the ILS keeps a log of that entire transaction history. This audit trail can be used for:

- Predicting future holds

- Calculating shelf space needed by collection

- Supporting decisions on digital licensing (“Should we buy this eBook too?”)

- Running last-copy retention audits for shared collections

One librarian said: “You think you’re checking out a book, but really, the system is checking you—for behavior, patterns, and collection gaps.”

And it all happens before the book even sits still again.

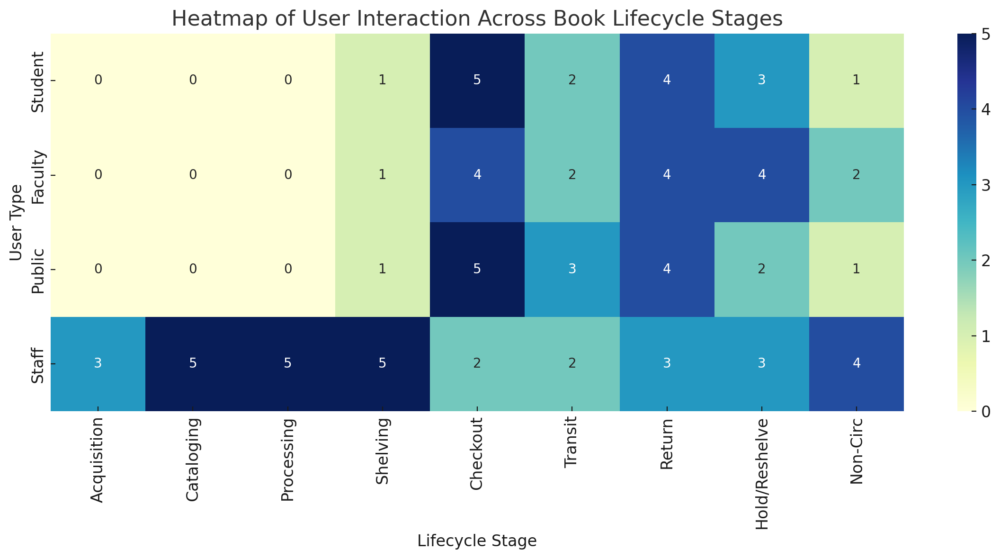

Students and the public interact heavily at checkout, return, and holds.

Faculty show steady interaction, especially at the hold and return stages.

Staff are involved deeply throughout the backend—especially in cataloging, processing, and shelving.

Non-Circulation Activities

Not every book gets checked out—but that doesn’t mean it’s idle. Non-circulating books are often the hardest-working items in a library’s collection, constantly influencing policy, space planning, and digital strategy. Let’s unpack some of the key ways these silent volumes shape the system.

1. In-House Use: The Invisible Metric

Here’s something I didn’t expect: most ILS systems don’t automatically track in-library use, unless staff manually rescan items found on carts or tables. That means a huge chunk of user engagement is basically invisible unless you capture it intentionally.

One branch I visited uses daily sweep carts and scans everything left out at the end of each day. That data is fed into a usage dashboard, which helps them spot titles that are heavily browsed but rarely checked out. Think: art books, dictionaries, legal reference texts. They even had a zine collection where nothing ever circulated, but every item showed up in sweep scans weekly.

2. Preservation Reviews: Hidden in Plain Sight

Non-circulating doesn’t mean untouched. In fact, many of these books go through condition audits more regularly than high-circulation titles, especially in academic and special collections. Think rare books, regional history volumes, or microfilm indexes.

Preservation teams often run environmental sweeps to check humidity levels, mold risk, or spine integrity. And some libraries are now tagging books with condition metadata—basically marking them in the catalog as “fragile” or “view by appointment only.” These tags trigger staff workflows that bypass self-checkout entirely.

One special collections librarian told me: “If a book hasn’t moved in five years, we still open it. That’s when things like silverfish show up.”

3. Digitization Requests: When One Scan Rewrites Policy

Occasionally, a single non-circulating item becomes digitally essential. This is where copyright, access, and digital preservation all collide. Maybe a professor requests a chapter scan, or a historian needs access to a fragile pamphlet.

Once that request comes in, the book gets flagged for special handling. That might involve scanning through controlled equipment (like BookEye scanners), creating high-res TIFFs, and even OCR tagging.

Here’s where it gets tricky: digitizing a non-circulating item can turn it into a circulation proxy. One library told me they tracked usage spikes on JSTOR-hosted PDFs that traced back to a single digitized pamphlet from their basement collection. Now they use those spikes to retroactively prioritize future digitization.

4. Collection Development: Ghost Data That Speaks Volumes

Non-circulating items are gold mines for data-informed weeding and growth strategies. If something hasn’t been touched in five years and isn’t showing up in in-house use stats, it’s probably a candidate for deselection—or at least relocation.

But here’s the nuance: some libraries retain materials purely for equity, heritage, or research potential. I saw a public branch that kept a full shelf of Romani history materials that hadn’t circulated in three years—because no other branch in the system had them. “We’re the last copy,” the manager said. “We’re not touching it.”

This is where non-circulation becomes a statement. Not all value is measurable through checkouts.

5. Special Exceptions: The Books That Break the Rules

Finally, some books are just… rule-breakers. Think course reserves, archive-only collections, rare books, and faculty deposit items. These don’t circulate, but their workflows are incredibly active.

Course reserves especially—those are usually on hourly loan timers or in-library use only, and they’re scanned in and out like library ping-pong. Some branches scan them 15–20 times per day. Others use self-checkout time limits that automatically trigger alerts if the book hasn’t been returned in 3 hours.

These workflows also sync with learning management systems like Canvas or Moodle, so students know what’s available. It’s circulation… without actual checkouts.

Finally..

At the end of the day, a single library book is more than an object—it’s a trigger, a metric, a proxy for user intent, and a quiet driver of policy. Whether it’s circulating or just sitting on a shelf, it’s always “doing” something.

What surprised me most?

Every book is a workflow.

And the more we pay attention to those micro-movements, the better we can shape systems that are smarter, more flexible, and yes—more human.