14 New Marine Species Discovered: From the “Popcorn” Parasite to Deep-Sea Oddities

Earth’s oceans continue to surprise us. In a groundbreaking update from marine researchers, 14 new marine species have officially been identified and described, along with two entirely new genera. These discoveries were announced by the Senckenberg Ocean Species Alliance (SOSA) — a global initiative under the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt — through their innovative publishing platform, Ocean Species Discoveries (OSD).

This project, now in its second major release, brings together over 20 scientists from different parts of the world. The team’s findings were published in the Biodiversity Data Journal on October 15, 2025.

Why This Matters

Our oceans are home to an estimated two million marine species, yet only a small fraction has been formally identified. Many are collected by researchers but remain unnamed for decades because of the slow pace of traditional taxonomy — the scientific process of describing and classifying species.

The Ocean Species Discoveries (OSD) platform was specifically designed to speed up this process. It allows scientists to publish concise yet high-quality species descriptions without the delays that usually come from broader ecological or genetic studies. By streamlining taxonomic publication, OSD aims to bridge the gap between discovery and recognition, ensuring that new species are formally documented before environmental pressures threaten them with extinction.

This is an increasingly urgent mission. Human activities — from deep-sea mining to ocean pollution and rising temperatures — are driving the loss of biodiversity at an alarming rate. Some of these newly discovered creatures live in extreme depths and fragile habitats, meaning they could be lost before we even learn about them.

The Project and How It Works

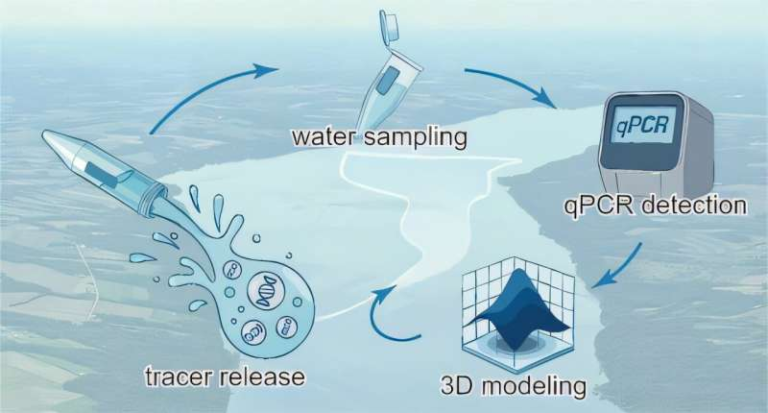

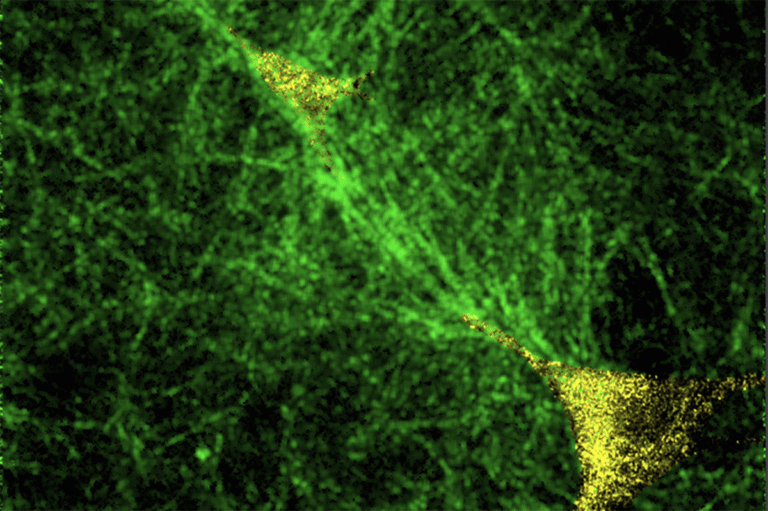

The Senckenberg team’s approach combines technology, global collaboration, and modern taxonomic efficiency. Their Discovery Laboratory in Frankfurt played a key role, equipped with tools such as light and electron microscopes, confocal imaging systems, molecular barcoding, and micro-CT scanners. These instruments allow researchers to create detailed 3D models and molecular profiles of species without damaging the delicate specimens.

The second issue of Ocean Species Discoveries (called OSD 13–27) builds on the first pilot edition, which had introduced 11 new species. The new release expands the work significantly, describing 14 newly identified marine invertebrates that include worms, mollusks, and crustaceans — species that span depths ranging from 1 meter to over 6,000 meters below the surface.

Some specimens were collected from remarkable deep-sea expeditions, including the R/V SONNE cruise SO293 AleutBio, led by Angelika Brandt. The expedition explored the Aleutian Trench, one of the most extreme oceanic environments on the planet. The cruise was funded by a BMBF grant (03G0293A), reflecting the German government’s support for deep-sea biodiversity research.

Meet the Newcomers: Species Highlights

The scientists described all 14 species and 2 genera in full detail, but a few stand out for their unusual appearance, behavior, or scientific importance.

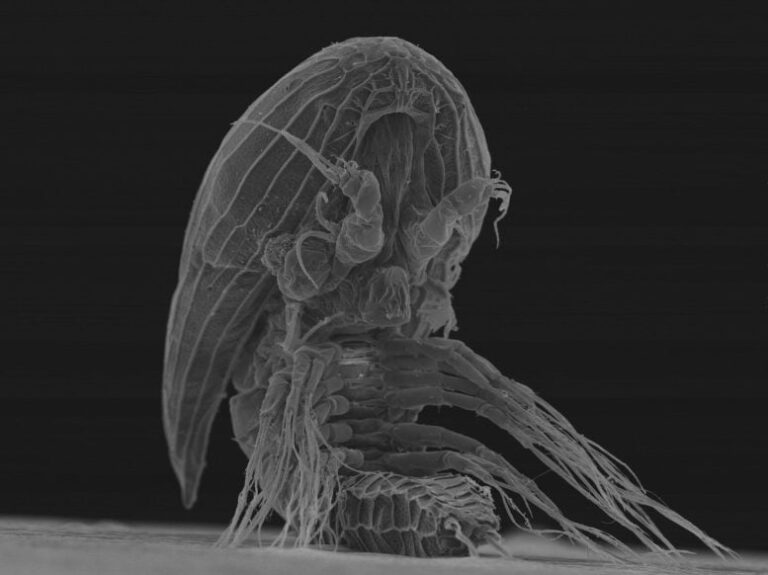

1. Zeaione everta — The “Popcorn” Parasite

This newly discovered parasitic isopod immediately grabbed attention thanks to its strange look. The female has bulbous, popped-kernel-like growths on her back, resembling pieces of popcorn. This unique appearance inspired the genus name Zeaione, derived from Zea, the corn genus.

Found in the intertidal zone of Australia, Zeaione everta represents an entirely new genus of crustaceans. Its discovery demonstrates how even coastal regions — often thought to be well-studied — can still reveal new and bizarre life forms.

2. Veleropilina gretchenae — A Deep-Sea Survivor

At a staggering 6,465 meters deep in the Aleutian Trench, scientists discovered Veleropilina gretchenae, a new species of monoplacophoran mollusk. Monoplacophorans are an ancient and rare group of marine snails once thought extinct until rediscovered in the 1950s.

This species is particularly important because it is one of the first monoplacophorans to have a high-quality genome sequenced directly from its holotype specimen. Its genetic data may provide clues about evolutionary links between mollusks and other marine animals that date back hundreds of millions of years.

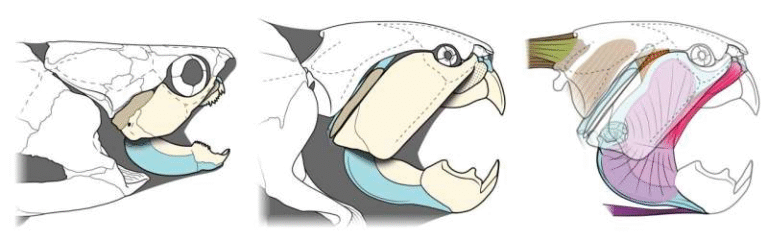

3. Myonera aleutiana — The Carnivorous Bivalve

Another fascinating find from the Aleutian Trench is Myonera aleutiana, a deep-sea carnivorous clam living at depths of 5,170–5,280 meters. It’s the deepest-living species of its kind ever recorded, about 800 meters deeper than any previously known relative.

What makes this species special is how it was studied: the entire anatomical description was done using non-invasive micro-CT scanning, generating over 2,000 tomographic images. This method revealed remarkable details of the bivalve’s internal tissues and organs without dissection, preserving the only known specimen in perfect condition.

4. Laevidentalium wiesei — The Tusk Shell with a Hitchhiker

This deep-sea tusk shell, found at over 5,000 meters, turned out to be more than just another new mollusk. When researchers examined it, they discovered a sea anemone attached to the concave end of its shell — a first-ever recorded interaction for the genus Laevidentalium.

This kind of relationship shows how even at crushing depths, where sunlight never reaches, marine life continues to form unexpected ecological partnerships.

5. Apotectonia senckenbergae — Honoring a Scientific Pioneer

One species, Apotectonia senckenbergae, was named in honor of Johanna Rebecca Senckenberg (1716–1743), whose contributions helped lay the foundation for the Senckenberg Society for Nature Research.

This small amphipod crustacean was discovered in mussel beds near hydrothermal vents at the Galápagos Rift, living 2,602 meters below the surface. These vents are nutrient-rich environments where heat and chemicals from Earth’s crust sustain unique ecosystems completely independent of sunlight.

6. Metharpinia hirsuta, Ferreiraella charazata, and Spinther bohnorum

Other new species in the collection include Metharpinia hirsuta, a bristly amphipod; Ferreiraella charazata, a small deep-sea worm; and Spinther bohnorum, a marine annelid with unusual bristle patterns. Each species contributes a piece to the puzzle of how life adapts to deep-sea pressures, cold temperatures, and complete darkness.

The Bigger Picture: Why Deep-Sea Discoveries Matter

The deep sea remains one of the least explored frontiers on Earth. Although it covers about 60% of our planet’s surface, scientists estimate that less than 1% of the deep ocean floor has been thoroughly studied.

Species like Veleropilina gretchenae and Myonera aleutiana highlight how much biodiversity remains hidden in extreme conditions — environments where temperatures can near freezing, and pressures are over 600 times greater than at sea level.

Every new discovery helps fill a gap in our understanding of how marine life has evolved and how it functions in these alien-like ecosystems. Many of these organisms may even hold biotechnological potential, with enzymes or adaptations that could inspire innovations in medicine, materials science, or robotics.

At the same time, the findings underscore how vulnerable these ecosystems are. Deep-sea mining and climate change could easily destroy habitats that we barely know exist. Scientists stress the importance of documenting this biodiversity before it disappears.

Making Taxonomy Faster

Traditional taxonomy — the art and science of describing species — can be painfully slow. Some species have sat in museum drawers for decades before being named. The OSD model changes that by allowing multiple researchers to contribute short, data-rich papers compiled into a single collective publication.

This approach makes taxonomy faster, more transparent, and more collaborative. It also ensures that scientists get credit for their discoveries quickly, without having to wait for years to publish longer monographs.

The Senckenberg Discovery Laboratory’s modern workflow — integrating morphology, molecular biology, and imaging — is a model for how taxonomy can evolve in the digital era. Instead of a single researcher working in isolation, teams now combine genetics, microscopy, and imaging data to create comprehensive species profiles.

The Ocean’s Hidden Majority

Experts estimate that at least two-thirds of marine species remain undescribed. Many of these live in deep-sea trenches, hydrothermal vents, or other hard-to-reach environments. Others are microscopic or cryptic — meaning they look almost identical to known species until examined genetically.

The more scientists look, the more they find. For example, studies have shown that in a single cubic meter of deep-sea sediment, there can be hundreds of distinct species of invertebrates, many of them unknown.

Projects like Ocean Species Discoveries demonstrate that taxonomy is not outdated science — it’s a vital tool for understanding life on Earth. Without accurate species descriptions, conservation laws can’t protect organisms that aren’t even officially recognized.

A Glimpse Into the Unknown

The 14 newly described species are a reminder that Earth’s greatest biodiversity frontier lies beneath the waves. Each of these creatures — from the popcorn-shaped parasite to the deep-sea bivalve — represents a small but crucial step toward understanding our planet’s hidden ecosystems.

The Senckenberg Ocean Species Alliance continues to encourage global cooperation among taxonomists, providing the tools, databases, and publishing infrastructure needed to make the discovery process smoother and faster.

It’s easy to get excited about the weird and wonderful nature of these animals — but beyond that curiosity, there’s a serious message here: We can’t protect what we don’t know exists.