3D Printing Food Is Emerging as a Serious Solution for Nutrition, Waste, and Custom Meal Design

The idea of 3D-printed food often sounds like something out of a futuristic kitchen, but current research shows it is becoming a real and increasingly practical tool for improving how we produce, customize, and preserve food. A significant amount of this work is happening at the University of Arkansas, where assistant professor of food engineering Ali Ubeyitogullari and his team are experimenting with printing everything from vegetable-based bioinks to enhanced nutritional gels. Their research explores how printed food can address issues like food waste, limited access to fresh produce, medical dietary restrictions, and even nutrient absorption challenges.

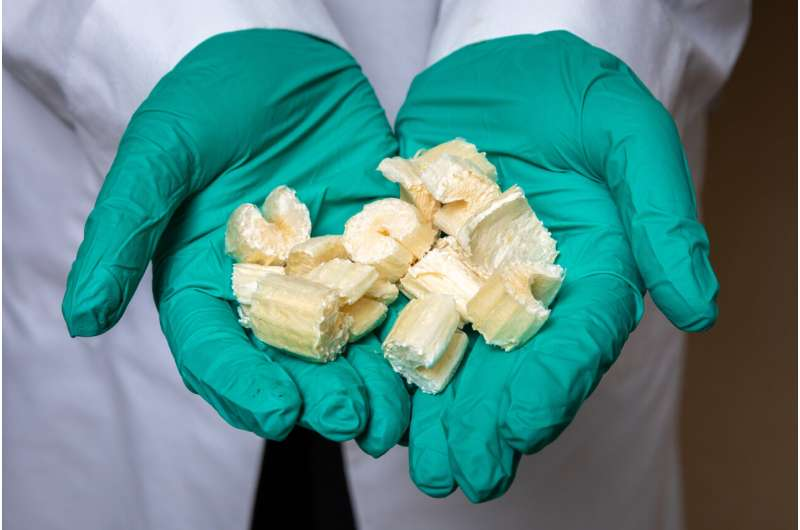

According to general estimates, around 30% to 40% of food in the U.S. is lost or wasted each year, a problem amplified by aesthetic standards that cause consumers to avoid “imperfect” produce. Ubeyitogullari’s lab sees 3D printing as a direct solution: fruits and vegetables that cannot be sold can be freeze-dried, dehydrated, or blended into bioinks, allowing them to be used in new forms rather than discarded. These bioinks can be shaped into appealing foods with software-controlled precision, and the team has already produced printed snacks shaped like recognizable characters using broccoli, carrot, or chocolate bioinks. The goal is straightforward — reducing waste while making nutritious foods easier and more enjoyable to eat, especially for children.

But waste reduction is only one part of the picture. Ubeyitogullari’s group is also focused on nutrition enhancement, an area where 3D printing offers unusual and powerful advantages. One challenge in nutrition science is the low bioavailability of many bioactive compounds found in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. These compounds help reduce the risk of diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders, yet humans often absorb only about 1% of what they consume. The compounds tend to degrade quickly and can be destroyed in the digestive system before reaching the bloodstream.

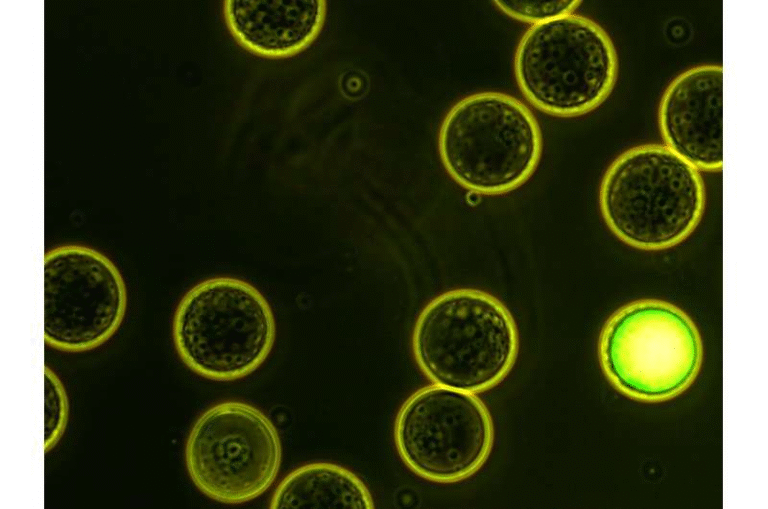

To counter this, the lab is studying a method known as encapsulation, which protects sensitive compounds by embedding them into food-grade biopolymer gels. These include everyday kitchen ingredients like starch, which forms gels with porous structures when heated. These pores can be loaded with nutrients and shield them from environmental factors. With 3D printing, researchers can precisely control where these compounds go inside a food structure, unlike traditional mixing methods where distribution is random and inconsistent.

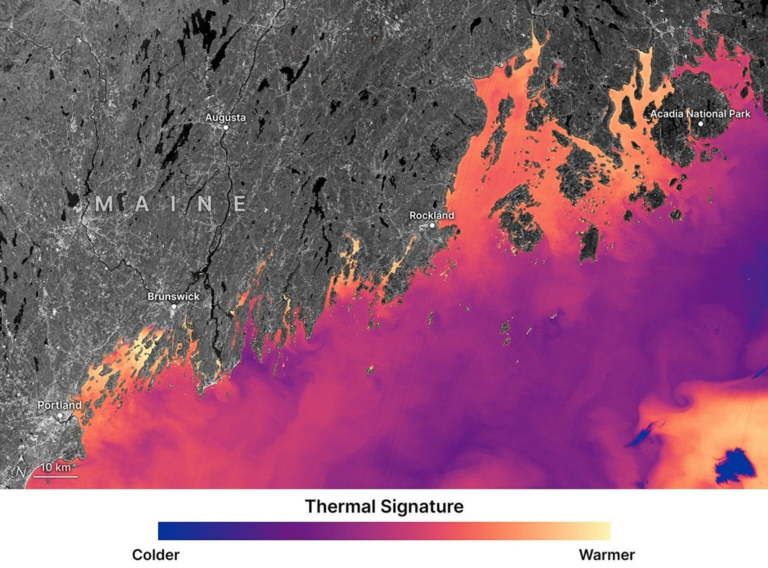

One application involves probiotics, which are beneficial microbes linked to gut health, immunity, and the gut-brain axis. Probiotics often die before reaching the colon because they cannot survive stomach acid. To address this, the team is using an alginate-pectin matrix — alginate being a seaweed extract and pectin being the familiar gelling agent used in jams. This matrix is resistant to the acidic environment of the stomach and releases the probiotics only once they reach the colon.

Another area of research involves sorghum, a drought-tolerant, gluten-free grain high in protein and fiber. Sorghum also carries anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, making it a promising material for nutrient-rich printing. Working with postdoctoral researcher Sorour Barekat, Ubeyitogullari is developing a 3D-printable sorghum protein gel, which could serve as a base for custom nutritious foods, plant-based snacks, or protein-dense meals.

The team is also experimenting with increasing the bioavailability of lutein, which supports eye health, and anthocyanins, known for their effects on visual and neurological function. In this project, researchers are using a dual-layer printing approach: a corn starch outer layer for easy extrusion and shape stability, and a zein protein core layer (derived from maize) because of its hydrophobic properties, which help stabilize delicate compounds. Experiments with nozzle speeds, ingredient ratios, and printing conditions are ongoing to refine the most efficient and stable structures.

Beyond nutrition science, one practical challenge the researchers are addressing is dysphagia, a swallowing disorder that affects an estimated 300,000 to 700,000 Americans every year, particularly older adults who must eat soft or pureed foods. These diets can reduce appetite and enjoyment because the food often looks unappetizing and indistinguishable. With 3D printing, soft foods can be restructured to look like their original forms — for example, a pureed carrot printed into the shape of a carrot — allowing patients to experience recognizable textures and shapes while still consuming safe, soft foods. This approach may help reduce weight loss and improve mental well-being in affected individuals.

3D printing could also simplify large-scale or emergency food production. Because printing requires only software adjustments and swapping out bioink cartridges, the technology avoids the need for costly reconfiguration of factory equipment. Portable 3D printing units could be deployed in humanitarian aid zones, disaster relief areas, or space missions, offering customizable nutrition tailored to the needs of soldiers, astronauts, or malnourished individuals.

The long-term vision includes household use. Just as microwaves were once met with skepticism — people once believed they made “radioactive food” — Ubeyitogullari expects that 3D printers will eventually become standard kitchen tools. In the future, people may use a smartphone app to order a meal with specific nutritional adjustments, supplements, or medications, and return home to find the freshly printed meal already prepared.

Below is additional background knowledge about 3D food printing to help readers understand the wider landscape:

How 3D Food Printers Work

Most 3D food printers use extrusion-based printing, pushing pastes or gels through nozzles. The feedstock often consists of purees, doughs, gels, or powdered materials mixed with liquids. Unlike manufacturing 3D printers that use plastics or resins, food printers rely entirely on edible, food-safe materials.

Benefits Over Traditional Processing

• Customization — precise control over nutrients, calories, flavors, and textures.

• Reduced Waste — ability to repurpose imperfect produce or surplus ingredients.

• Consistency — uniform structure and dosing across every printed item.

• Automation — minimal manual intervention once printing starts.

Current Limitations

• Printing can be slow and lacks the mass-production efficiency of factories.

• Equipment and materials can be expensive.

• Public perception remains skeptical or confused.

• Safety guidelines and regulations are still developing.

Despite these limitations, ongoing research continues to make printed foods more stable, nutritious, affordable, and practical. As technological barriers shrink, 3D-printed food is expected to move from specialized labs and demonstration kitchens into hospitals, homes, and even remote environments where flexible nutrition is crucial.