A Tug-of-War Explains a Decades-Old Question About How Bacteria Swim

Scientists have finally cracked a long-standing mystery about how swimming bacteria change direction, and the answer turns out to be far more dynamic than previously believed. In new research published in Nature Physics, researchers propose that bacterial movement is controlled not by a passive, orderly chain reaction, but by an active mechanical tug-of-war happening inside one of biology’s most fascinating molecular machines: the flagellar motor.

This discovery reshapes how scientists understand bacterial motion, chemotaxis, and even how living systems operate far from equilibrium.

How Bacteria Swim Using Tiny Molecular Motors

Many bacteria move through liquids using long, whip-like tails called flagella. These tails rotate like propellers, pushing the cell forward. At the base of each flagellum is a complex rotary engine embedded in the cell membrane, known as the flagellar motor.

What makes this motor remarkable is its ability to spin in two opposite directions:

- Counterclockwise (CCW) rotation usually produces smooth, straight swimming.

- Clockwise (CW) rotation causes the bacterium to tumble and change direction.

By alternating between these two modes, bacteria can navigate their environment, moving toward nutrients and away from harmful substances. This behavior is central to bacterial chemotaxis, a field that has been studied intensely since the mid-20th century.

The Old Domino Effect Model and Its Limits

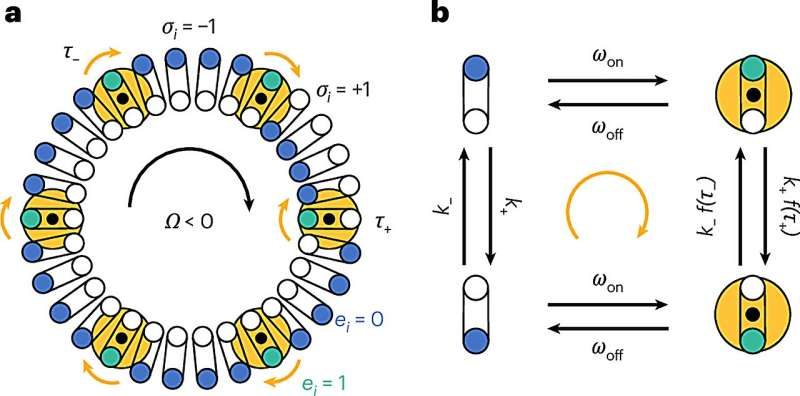

For decades, scientists explained motor switching using what’s often called an equilibrium domino model. According to this idea, the flagellar motor contains a ring of about 34 proteins, and each protein can exist in one of two conformations, favoring either clockwise or counterclockwise rotation.

The model assumed that neighboring proteins influence each other locally. If enough adjacent proteins flipped into one state, others would eventually follow, much like dominos falling in sequence. Once a critical number switched, the entire motor would change direction.

This theory made sense conceptually, but it ran into trouble when researchers examined experimental data more closely.

A Statistical Clue That Something Was Missing

Measurements of how long bacterial motors stayed rotating in one direction revealed a surprising pattern. If the domino model were correct, motor switching should be memoryless, meaning the probability of switching would be the same no matter how long the motor had been spinning in a given direction.

Instead, experiments showed a distinct peak in the distribution of rotation times. The motor tended to switch most often after a certain duration, a pattern that simply cannot arise from a purely equilibrium process.

This was a major red flag. It suggested that energy was actively shaping the switching behavior, rather than the system passively settling into equilibrium.

A New Idea Based on Motor Mechanics

The new explanation comes from researchers Henry H. Mattingly and Yuhai Tu at the Flatiron Institute. Their work builds on recent advances in understanding the physical structure of the flagellar motor.

The motor’s core structure, known as the C-ring, functions like a large central gear. Surrounding it are smaller components called stators, which act like tiny gears driven by ion flow. These stators always rotate in the same direction, but depending on how they contact the C-ring, they can push the motor either clockwise or counterclockwise.

Each protein in the C-ring behaves like a gear tooth. When a tooth contacts the stator on one edge, it favors clockwise rotation. When it contacts the opposite edge, it favors counterclockwise rotation.

Where the Tug-of-War Begins

Problems arise when not all gear teeth agree.

Some proteins may adopt conformations that push the motor clockwise, while others push it counterclockwise. Because all these teeth are mechanically linked through the rigid C-ring, conflicting forces build up across the entire motor.

This is where the tug-of-war comes in.

If a single protein flips while most others remain aligned, it experiences strong opposing forces from the rest of the motor. These forces make it more likely to flip back and rejoin the majority. But if enough proteins dissent at once, the balance of forces shifts, and the entire motor abruptly switches direction.

The researchers call this mechanism global mechanical coupling, emphasizing that the behavior of each protein depends on forces distributed across the whole motor, not just its immediate neighbors.

Why This Is a Non-Equilibrium Process

Unlike the old domino model, this new mechanism is actively driven by energy. The stators are not just power supplies for rotation; they directly influence switching by injecting mechanical energy into the system.

This energy input explains the experimentally observed peak in switching times and confirms that the motor operates out of equilibrium. In other words, the system constantly dissipates energy to maintain its function, which is a hallmark of living systems.

The new model shows that direction switching is directional, cooperative, and energy-dependent, aligning far better with experimental observations.

The Role of Chemical Signaling

Mechanical forces are not acting alone. The motor is also regulated by a signaling molecule called CheY-P. This molecule binds to specific proteins in the C-ring and biases them toward one rotational state or the other.

CheY-P levels change based on environmental signals detected by the bacterium, linking external sensing to internal mechanical response. The new model integrates this chemical signaling with mechanical forces, providing a more complete picture of how bacteria make movement decisions.

Why the Flagellar Motor Matters Beyond Bacteria

The bacterial flagellar motor is often described as one of nature’s most elegant molecular machines. Because it is so well studied, it serves as a powerful testing ground for ideas about nonequilibrium physics in biology.

Insights gained from this system may help scientists understand other complex biological processes where mechanical forces, energy dissipation, and collective behavior play crucial roles, from muscle contraction to neural activity.

What Comes Next for This Research

While the new model explains many previously puzzling observations, it is not the final word. The researchers note that their theory predicts certain switching times that are slightly shorter than those seen in experiments.

Future work will focus on refining the model and incorporating more detailed experimental data. As often happens in biology, solving one mystery has revealed new questions waiting to be explored.

Far from being a “solved” field, bacterial chemotaxis continues to surprise researchers, proving that even the simplest organisms can teach us deep lessons about how life works.

Research paper:

Mechanical origin for non-equilibrium ultrasensitivity in the bacterial flagellar motor, Nature Physics (2026)

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-03105-2