Advanced Hearing in a 250-Million-Year-Old Mammal Ancestor Was Far More Sophisticated Than We Thought

One of the defining traits of modern mammals is highly sensitive hearing, made possible by a complex middle ear that transmits sound efficiently from the environment to the brain. For decades, scientists believed this ability evolved relatively late, after early mammals had fully separated their ear bones from the jaw. New research now challenges that long-standing assumption and pushes the origin of mammal-like hearing much further back in time.

A recent study led by researchers at the University of Chicago reveals that Thrinaxodon liorhinus, a small mammal-like animal that lived around 250 million years ago during the early Triassic period, likely had the ability to hear airborne sounds far more effectively than previously believed. Using modern engineering simulations applied to fossil anatomy, the researchers show that this early mammal relative may have relied primarily on an eardrum-based hearing system, not just vibrations transmitted through bone.

Why Hearing Matters in Mammal Evolution

Hearing is not just about detecting sound—it is about sensitivity, frequency range, and the ability to distinguish subtle differences in the environment. Modern mammals owe much of this ability to a middle ear composed of an eardrum and three tiny bones: the malleus, incus, and stapes. This system amplifies sound vibrations and allows mammals to hear both faint and high-frequency sounds.

This innovation is thought to have been especially important for early mammals, many of which were likely small, nocturnal animals living alongside dinosaurs. Being able to hear predators, prey, and mates in the dark would have provided a major survival advantage.

Until now, scientists believed that such refined hearing only emerged well after early mammal ancestors had evolved a fully detached middle ear. The new findings suggest that this transformation began tens of millions of years earlier.

Meet Thrinaxodon, a Key Mammal Relative

Thrinaxodon was a member of a group called cynodonts, animals that occupied an evolutionary middle ground between reptiles and mammals. Cynodonts already showed several mammal-like traits, including specialized teeth, changes to the palate, improved breathing mechanics, and likely warm-blooded metabolism. Many scientists also suspect they had fur, though direct evidence is rare.

What made cynodonts particularly intriguing is the arrangement of their ear bones. In early forms like Thrinaxodon, the bones that would later become the mammalian middle ear were still attached to the jaw. This led to the assumption that they could not hear airborne sounds efficiently and instead relied on bone conduction, including a behavior known as “jaw listening,” where vibrations are picked up through contact with the ground.

A 50-Year-Old Hypothesis Put to the Test

More than fifty years ago, a paleontologist named Edgar Allin proposed an alternative idea. He suggested that early cynodonts might have had a primitive eardrum stretched across a hooked structure in the jaw, acting as a precursor to the modern tympanic membrane. At the time, this idea was compelling but impossible to test.

The problem was not the hypothesis itself, but the lack of tools. Fossils rarely preserve soft tissue, and traditional anatomical studies could not determine whether such a structure would actually work for hearing.

That limitation has now changed.

Turning Fossils Into an Engineering Problem

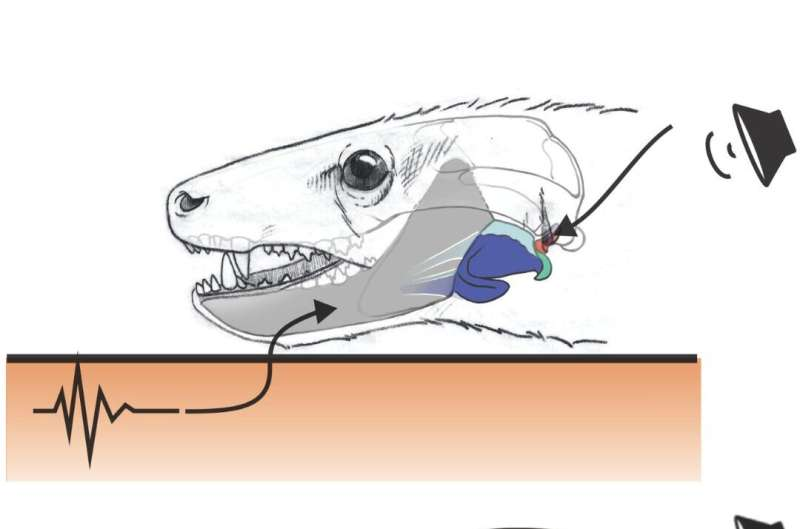

The research team, led by graduate student Alec Wilken, used a well-preserved Thrinaxodon fossil housed at the University of California Berkeley Museum of Paleontology. The specimen was scanned using high-resolution CT imaging at the University of Chicago’s PaleoCT Laboratory, producing a detailed 3D digital model of the skull and jaw.

This digital reconstruction captured precise information about shape, size, curvature, and spatial relationships between bones—exactly what engineers need to analyze mechanical performance.

The team then applied finite element analysis, a powerful engineering method commonly used to study stress and vibration in structures like bridges, aircraft, and engines. Using specialized software, they simulated how different sound pressures and frequencies would interact with Thrinaxodon’s jaw, ear bones, and a hypothesized eardrum.

Material properties such as bone density, ligament flexibility, muscle behavior, and skin thickness were estimated using data from living animals, allowing the researchers to model how sound would travel through the system.

What the Simulations Revealed

The results were clear and striking. The simulations showed that Thrinaxodon’s anatomy could support an eardrum large enough to efficiently transmit airborne sound. Vibrations entering this membrane would have moved the attached ear bones in a way that generated sufficient pressure to stimulate the auditory nerves.

In fact, the models demonstrated that eardrum-based hearing was far more effective than bone conduction alone. While Thrinaxodon may still have relied partially on jaw listening, most of its hearing likely came from this early tympanic system.

This means that mammal-like hearing did not suddenly appear after the middle ear detached from the jaw. Instead, it evolved gradually, with functional airborne hearing emerging while the ear bones were still part of the jaw structure.

Crucially, this pushes the origin of advanced hearing back by nearly 50 million years earlier than previously thought.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research reshapes our understanding of how and when one of the most important mammalian traits evolved. It shows that functional innovations can arise before anatomical structures reach their final form, a concept with broad implications for evolutionary biology.

The study also highlights the growing role of computational biomechanics in paleontology. Fossils are no longer just static remains; with modern imaging and simulation tools, scientists can test how ancient animals moved, breathed, and now—even how they heard.

By treating a fossil like a living mechanical system, researchers can answer questions that once seemed permanently out of reach.

Extra Context: How Mammalian Hearing Evolved

In modern mammals, the middle ear bones evolved from jaw elements found in reptile ancestors. Over time, these bones gradually reduced their role in feeding and became specialized for sound transmission. This transition is one of the most remarkable examples of evolutionary repurposing.

The new findings suggest that hearing performance improved before the complete structural separation occurred. This means early mammal relatives may have enjoyed many of the sensory advantages of mammals long before they fully looked or behaved like them.

It also supports the idea that sensory evolution played a key role in the success of mammals, helping them adapt to ecological niches that other animals could not easily exploit.

The Bigger Picture

This study is a reminder that evolution rarely works in sudden leaps. Instead, it builds complex systems step by step, often testing new functions long before the final anatomy is complete.

By combining paleontology with engineering, researchers are uncovering a far more nuanced picture of our deep evolutionary history—one where early mammal relatives were already experimenting with sophisticated ways of sensing the world.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2516082122