Airborne eDNA Monitoring Shows How Salmon Can Be Counted Straight From the Air

The idea of counting salmon without ever touching the water sounds almost too convenient, but a new study from the University of Washington shows that it’s not only possible—it’s surprisingly effective. Researchers have demonstrated that environmental DNA (eDNA) released by salmon during their fall migration can drift into the air, where it can be collected on simple filters placed several feet from the stream. The study provides detailed evidence that DNA shed by aquatic animals can move between water and air, allowing scientists to estimate salmon activity without relying solely on traditional visual counts.

This research took place on Issaquah Creek in Washington, near the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, during the annual run of Coho salmon. These fish are known for their energetic upstream migration, and as they leap and thrash near the surface, they shed bits of skin and organic material—tiny traces of DNA that normally settle in water. Until now, very few studies explored the possibility of detecting that DNA in airborne particles, and none tied it directly to tracking migration numbers.

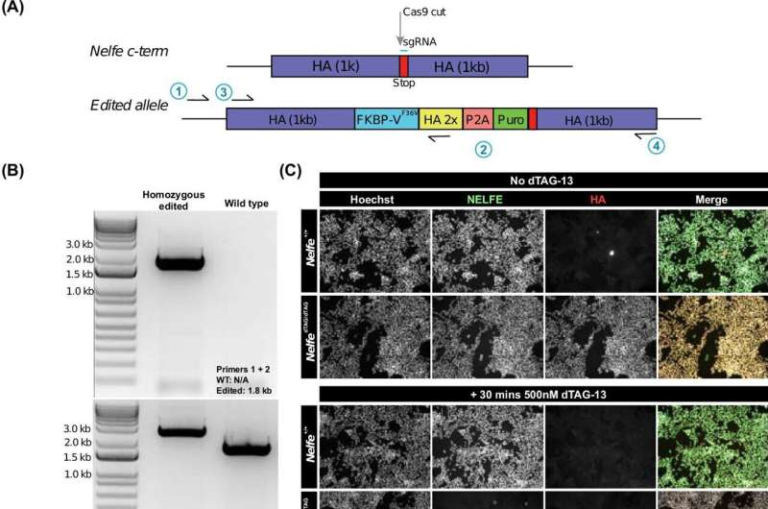

The researchers placed a series of air filters 10 to 12 feet from the stream, leaving them in place for 24-hour periods on six separate days between August and October. They tested four sampling methods each time: three types of vertical filters and a 2-liter open tub of deionized water designed to capture falling particles. Although the amount of salmon DNA collected from the air was dramatically lower than what they found in water—around 25,000 times less—the concentration still rose and fell in sync with the actual movement of fish upstream.

After collection, the team washed the eDNA from each filter in a laboratory and used a Coho-specific marker and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification to quantify the DNA. They then compared airborne eDNA levels with water eDNA concentrations and with official hatchery visual fish counts, combining these data into a model that reflected the fluctuations in salmon abundance during the fall migration. Even with its low absolute concentration, airborne eDNA consistently tracked the same trends seen in traditional monitoring.

The significance of this is twofold. First, it confirms that aquatic eDNA can become airborne, drifting beyond the shoreline and settling on nearby surfaces. Researchers have occasionally detected unexpected aquatic DNA in air studies before, but this experiment directly shows how material expelled by fish can move through the environment. Second, the method proves that air sampling may become a remote-friendly monitoring tool for salmon and potentially other species. Unlike water pumps, cameras, or electrical sensors, passive air sampling requires no electricity, making it practical in rugged or isolated locations.

While airborne eDNA does not provide an exact fish count, it indicates where salmon are and how their relative abundance changes over time. For population monitoring, this is extremely valuable. Salmon runs are used to assess river health, set fishing limits, and shape conservation strategies. A lightweight, low-maintenance tool that complements traditional methods could streamline fieldwork and offer a more complete picture of ecosystem dynamics.

However, the researchers emphasized that more work is needed. Environmental factors such as rain, humidity, wind, and temperature may significantly influence how much eDNA disperses into the air and how far it can travel. Rain could wash particles downward, wind might carry them in unpredictable directions, and humidity may affect the survival time of airborne DNA fragments. These variables introduce complexities that must be fully understood before airborne eDNA can be used as a standardized monitoring method. The team plans to investigate these influences in future experiments.

The study also highlights how rapidly eDNA science is expanding. Over the past decade, environmental DNA has become a powerful tool in conservation biology, often used to detect endangered, cryptic, or invasive species in water systems. Airborne eDNA has been explored for plants, insects, and some terrestrial animals, but applying it to aquatic species marks a major step forward. It suggests that the boundary between aquatic and terrestrial monitoring is more porous than once believed.

Below are several additional sections offering context and broader insights into the science behind this study.

How Salmon Migration Produces Environmental DNA

Salmon shed DNA throughout their lives, but shedding increases noticeably when they swim aggressively in shallow streams during migration. As they push upstream, they make constant contact with water surfaces, gravel, and other fish. All of this releases minute particles—skin cells, mucus, scales, and other biological material—that carry genetic signatures. These particles disperse quickly in water and may remain detectable for hours to days depending on temperature, flow rate, and microbial activity.

The discovery that some of this material also becomes airborne—through splashes, aerosols, and possibly bubble-bursting events—helps researchers rethink how DNA moves through ecosystems. It also raises interesting questions about how far eDNA can travel and how long it stays intact outside of water.

Why Airborne eDNA Matters for Conservation

Monitoring salmon populations is essential for managing fisheries, protecting habitat, and supporting hatcheries. Traditional counting methods, such as having people stand by the river and visually record fish passing through, are effective but labor-intensive. Camera systems and sonar devices provide more automation, but they require reliable power sources and are costly to maintain.

Airborne eDNA sampling offers a low-cost, low-infrastructure alternative, especially in situations where remote areas lack equipment or where sensitive habitats benefit from minimal disturbance. Because the method is passive, it can be deployed for long periods without regular attention.

As airborne eDNA tools improve, they may allow wildlife managers to monitor multiple rivers simultaneously or detect the presence of rare species with fewer field visits. It could even help scientists study how climate change influences salmon behavior by providing long-term records of migration patterns with minimal labor.

Challenges That Must Be Solved Before Widespread Adoption

Despite its promise, airborne eDNA monitoring faces several technical challenges:

• Extremely low concentrations mean that DNA detection must be precise and contamination-free.

• Weather effects introduce variability that could complicate data interpretation.

• Differences in filter types and deployment heights may change how much DNA is captured.

• Background DNA noise from other organisms or environmental sources must be accounted for.

As researchers refine these techniques, standard protocols will emerge, allowing scientists in different regions to compare data reliably.

A Look Toward the Future of Airborne DNA Research

This study demonstrates that airborne eDNA can reflect real-time biological events happening in water. As technology improves, scientists may eventually use air-based sampling to survey entire watersheds, identify spawning hotspots, detect invasive fish, or track migration timing shifts caused by warming temperatures. The ability to link air, water, and organism biology opens new possibilities for ecosystem monitoring and environmental decision-making.

The University of Washington researchers stress that they are still exploring the boundaries of what airborne eDNA can do. Yet the evidence so far shows clear potential. A method that once seemed improbable—catching salmon DNA drifting through the air—may soon play a role in managing some of the world’s most important fish populations.

Research Reference

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-26293-6