American Kestrels Are Emerging as a Valuable Food-Safety Partner for Michigan Cherry Growers

Michigan’s cherry harvest season may be long over, but many growers in northern Michigan are already looking ahead to something unexpected that could influence next year’s crop: the return of the American kestrel, the smallest falcon in the United States. These tiny raptors have been known for years as natural deterrents of fruit-eating birds, but new research shows they may also play an important role in reducing food-safety risks in orchards. A forthcoming study from Michigan State University, scheduled for publication on November 27 in the Journal of Applied Ecology, examines how kestrels affect bird behavior, crop damage, and signs of contamination in sweet cherry orchards.

This article takes a clear, straightforward look at what the researchers found, why it matters, and how kestrels might fit into broader agricultural practices.

How Kestrels Help Cherry Growers

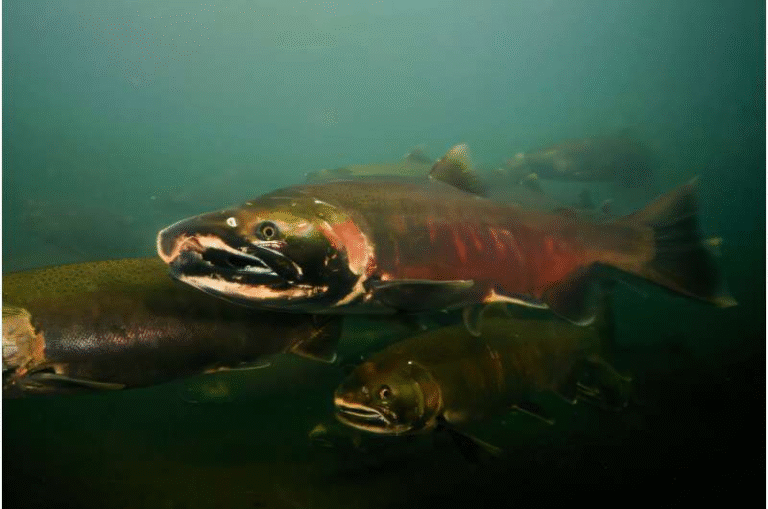

The American kestrel is small but effective. As a bird of prey, it hunts insects, mice, and small birds. This predatory presence alone is enough to convince many fruit-eating species—such as robins, grackles, and starlings—to avoid areas where kestrels are nesting. These smaller birds account for significant fruit losses every year, even in orchards using deterrents like nets, noisemakers, sprays, and scare devices. In major sweet-cherry-producing states including Michigan, Washington, Oregon, and California, growers regularly lose 5% to 30% of their harvest to bird damage despite active management.

The MSU researchers wanted to understand how much of a difference kestrels could make when provided suitable nesting environments. They installed nest boxes in eight sweet cherry orchards across northern Michigan. Since kestrels naturally seek out cavities to raise their chicks, they quickly moved in. As the harvest season approached, the research team recorded every bird species they heard or saw in each orchard.

The results showed a significant shift in bird activity. Orchards with nesting kestrels saw a more than tenfold reduction in visits from fruit-eating birds. With fewer intruders in the trees, the cherries experienced dramatically less pecking and fruit loss. The kestrels, simply by occupying the space and patrolling their territory, created an environment that discouraged hungry birds from approaching.

Food-Safety Implications and Specific Findings

While saving fruit is a major win, the study paid equal attention to a second issue: the risk of contamination from bird droppings. Birds that feed in orchards leave feces on branches, leaves, and potentially even the fruit itself. Some consumers and food-safety experts worry that these droppings may contain pathogens linked to human illness.

The researchers tracked signs of droppings in orchards and discovered that areas closer to kestrel nest boxes had three times fewer bird droppings on branches compared to areas without kestrels nearby. This reduction matters because bird feces can sometimes contain Campylobacter, a bacterium that causes foodborne illness and symptoms such as diarrhea, stomach cramps, and fever.

To understand the risk more clearly, the team conducted DNA analysis on the droppings they collected. They found that 10% of the samples carried genetic material associated with Campylobacter. This doesn’t necessarily mean an infectious dose was present, but it demonstrates that the pathogen circulates in bird populations around farms.

Importantly, despite these findings, no outbreaks of foodborne illness tied to Campylobacter have ever been linked to cherries. Only one known outbreak in the U.S. has been traced to birds at all—a 2008 incident involving migratory cranes contaminating pea fields in Alaska. Still, the researchers emphasize that kestrels help reduce the opportunities for contamination by keeping potentially risky birds away.

One limitation is that kestrels themselves also produce droppings. However, the research team noted that the reduction in pest bird presence far outweighs any droppings produced by the kestrels. The net effect is a significant decrease in overall contamination indicators.

Understanding Why Kestrels Are Effective

Kestrels use a hunting strategy known as hovering, where they beat their wings rapidly to remain in place in midair while scanning the ground. Their distinctive hovering and territorial behavior serve as strong visual cues to smaller birds that predators are present.

Unlike artificial deterrents—such as loud noises or reflective materials—kestrels do not rely on novelty. Birds often become accustomed to scare devices and eventually ignore them. Natural predators, on the other hand, consistently trigger avoidance behavior.

Nest boxes are remarkably low-maintenance. Once installed, they require minimal upkeep and cost far less than nets or electronic deterrent systems. The presence of kestrels also aligns well with sustainable farming practices, reducing reliance on interventions that may be expensive, labor-intensive, or disruptive.

Where Kestrels Fit Into Broader Agricultural Strategies

Kestrels are not a universal solution to bird problems. Their nesting behavior makes them more likely to settle in certain environments than others. Farmers in regions unsuitable for kestrel populations may not experience the same benefits.

Still, for areas where kestrels naturally thrive or can be encouraged to nest, they offer a low-cost, environmentally friendly addition to a farm’s pest-management toolkit.

The researchers also note that the potential food-safety benefits extend to crops beyond cherries. Many produce items—especially leafy greens—have faced contamination concerns. If kestrels can reduce the presence of pest birds in those fields as well, they could become part of broader integrated food-safety systems. However, more studies would be needed to confirm this in other crop types.

Additional Facts About American Kestrels

Because the kestrel plays such a central role in this study, it’s worth understanding some background about the species:

Basic Characteristics

- The American kestrel is the smallest falcon in North America, typically weighing 3–6 ounces.

- They display bright coloration, with males featuring blue-gray wings and females sporting reddish-brown tones.

- Their diet includes insects, small mammals, and small birds—making them effective natural pest controllers.

Habitat and Nesting

- Kestrels naturally nest in tree hollows, cliff crevices, and other cavities.

- Agricultural areas with open fields make ideal hunting grounds.

- Nest boxes have been widely used in conservation efforts to support kestrel populations, which have declined in some regions due to habitat loss.

Role in Agriculture

- Beyond cherries, kestrels have been used in orchards, vineyards, and crop fields to deter pest species.

- Some farms in the western U.S. have used nest-box programs for decades, reporting reduced crop damage.

- Encouraging kestrels aligns with wildlife-friendly agriculture, maintaining biodiversity while supporting production.

What This Study Means for the Future

The MSU study shows that kestrels provide two clear benefits: protecting fruit from damage and reducing signs of contamination. The findings support the idea that natural predators can contribute meaningfully to both agricultural productivity and food safety.

The researchers stress that kestrels are not a complete solution to all bird-related problems, but they are a strong addition to existing approaches. With low installation and maintenance costs, kestrel nest boxes offer an appealing option for farmers looking to reduce losses and promote safer produce.

As more growers look for alternatives to chemical or artificial deterrents, the role of natural predators like kestrels may continue to grow. This study adds valuable, data-driven evidence that supports their usefulness in orchard settings.

Research Reference:

Falcons Reduce Pre-Harvest Food Safety Risks and Crop Damage From Wild Birds

https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.70209