Ancient Origins of the Human-Biting Mosquito: New Study Rewrites the Story of Culex pipiens form molestus

For years, scientists believed that the human-biting mosquito known as Culex pipiens form molestus evolved quite recently—around 200 years ago—in the dark tunnels of London’s Underground. It was considered one of the best examples of how animals can rapidly adapt to urban life, evolving from its bird-biting relative, Culex pipiens form pipiens.

But new research led by Princeton University has completely upended that story. Published in the journal Science, the study shows that this mosquito didn’t arise in modern cities at all—it actually originated more than 1,000 years ago, probably in Ancient Egypt or the broader Mediterranean region. The findings not only rewrite a famous chapter in urban evolutionary biology but also carry important implications for understanding how diseases like West Nile virus spread from birds to humans.

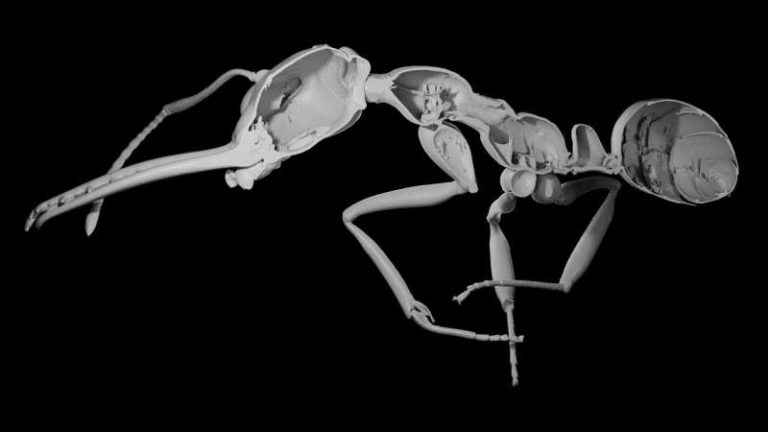

A Closer Look at the Mosquito in Question

The mosquito species Culex pipiens is incredibly widespread, found across most of the temperate world. Within this species, there are two main forms:

- Form pipiens – the typical above-ground mosquito that prefers to bite birds.

- Form molestus – the urban, underground-dwelling mosquito that prefers to bite humans.

Both look nearly identical, but their behaviors are strikingly different. Pipiens depends on seasonal cues to breed and usually needs open air and daylight. Molestus, on the other hand, thrives in basements, subway tunnels, and other enclosed spaces. It can reproduce year-round without needing a blood meal, which makes it perfectly adapted to city life.

Because molestus was first noticed during World War II in London, it became legendary as the so-called “London Underground mosquito.” For decades, this was thought to be a modern example of rapid evolution—a species that had quickly adapted to the strange underground world of subways and sewers.

The Princeton Study: Setting the Record Straight

The new research, led by Lindy McBride and Yuki Haba from Princeton University, involved a massive global collaboration. The team partnered with about 150 organizations around the world and collected roughly 12,000 mosquito samples representing both pipiens and molestus forms.

From these, 800 samples were selected for detailed genetic analysis. Haba, now a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University, personally extracted DNA from each of these mosquitoes to study their genetic patterns. The results were clear: molestus did not evolve recently in Europe, but instead emerged thousands of years ago alongside early agricultural societies in the Middle East or Mediterranean.

This discovery suggests that molestus first adapted to human environments—villages, stored water, animal shelters—long before modern cities even existed. Over time, it became a distinct lineage that could survive underground or in urban spaces, eventually spreading across the world.

Evolutionary Clues Hidden in DNA

The researchers compared genetic sequences from mosquitoes living on five continents. Their DNA analysis revealed that the split between molestus and pipiens likely happened between 1,000 and 10,000 years ago, well before industrialization or subways.

Interestingly, the genetic diversity of molestus was far greater than expected for something that supposedly evolved in the 1800s. This was a key clue that the mosquito’s evolutionary roots were ancient.

The study also looked at gene flow, or hybridization, between the two forms. Scientists have long suspected that when molestus (the human-biter) mates with pipiens (the bird-biter), their hybrid offspring could bite both birds and humans. This dual feeding behavior can act as a bridge for viruses that jump between species.

However, the Princeton team found that hybridization happens less often than previously thought. It’s not widespread but does occur more frequently in large cities, where both forms overlap. This urban mixing may create mosquito populations capable of transmitting diseases like West Nile virus more efficiently.

Why West Nile Virus Matters

West Nile virus (WNV) is a disease that circulates naturally among birds but can spill over into humans when mosquitoes feed on both hosts. While most human infections cause mild or no symptoms, severe cases can lead to neurological damage or death.

The discovery that molestus—and its hybrids—play a role in this process is significant. In cities, where both bird populations and underground mosquitoes coexist, the risk of spillover increases. If hybrid mosquitoes become more common, they could act as perfect “connectors,” picking up the virus from birds and transmitting it to people.

This finding highlights how urbanization can indirectly promote disease spread, not just by increasing human density but also by influencing mosquito genetics and behavior. Understanding where and when hybridization occurs could help target mosquito control efforts more effectively in high-risk areas.

How Scientists Once Got It Wrong

The idea that molestus evolved in the London Underground stuck around for decades because it seemed to fit so perfectly. The mosquito was first documented in large numbers during WWII, biting people sheltering in subway tunnels. Since it thrived in these dark, isolated spaces, it looked like a textbook example of evolution in action—a species adapting to a man-made environment within a short time.

However, there were always cracks in the theory. Similar mosquitoes were later found in New York, Tokyo, Cairo, and Moscow, often in basements and underground systems. This widespread presence suggested that molestus didn’t just appear in one city but had been quietly living alongside humans for much longer. The new genomic evidence finally confirms this: the “London Underground mosquito” is actually an ancient hitchhiker of human civilization.

Implications for Public Health

By revealing the mosquito’s deep history, the study changes how we think about mosquito evolution, disease ecology, and urban adaptation. It shows that mosquitoes can maintain specialized human-biting behavior over millennia, suggesting strong evolutionary pressure to feed on us.

For public-health researchers, it also underlines the importance of monitoring mosquito genetics in urban areas. If hybridization is more common in big cities, these regions might face greater risk of viral transmission, especially as climate change alters mosquito habitats and breeding cycles.

Urban planners and disease-control programs may need to consider how underground infrastructure—from subway tunnels to drainage systems—provides ideal environments for mosquitoes like molestus to thrive year-round.

The Broader Significance: Urbanization and Evolution

This study adds to a growing body of research showing that urbanization is a powerful evolutionary force. Cities create extreme environments—constant temperatures, limited daylight, pollution, and abundant human hosts—that push species to adapt quickly.

But in this case, the mosquito didn’t evolve because of cities; instead, it was already pre-adapted to human living. Our modern urban landscapes simply gave it more places to flourish.

It’s a reminder that humans have been shaping the evolution of other species for thousands of years—sometimes without even realizing it. The very conditions that made agriculture possible—stored water, animal pens, and dense human populations—also helped create mosquitoes that now pose challenges for global health.

What’s Next

The Princeton team emphasizes that more research is needed to understand how hybridization affects disease transmission. They plan to expand sampling in both urban and rural regions to track where gene flow happens and how it influences biting preferences.

Future studies could also explore whether climate change might alter mosquito breeding patterns, potentially shifting where molestus and pipiens interact. Understanding these dynamics is critical for predicting future outbreaks of West Nile and other mosquito-borne diseases.

A Fascinating Rewrite of a Classic Story

In summary, Culex pipiens form molestus didn’t evolve in London’s subway. It’s a far older, globally distributed mosquito that likely originated in ancient human settlements over a millennium ago. By tracing its genetic roots, scientists have not only corrected a long-standing myth but also opened new paths for studying how urbanization, evolution, and public health intersect.

This small insect—once thought to be a modern product of city life—turns out to be an ancient companion of humanity, adapting alongside us since the dawn of civilization.

Research Reference: Yuki Haba et al., “Ancient origin of an urban underground mosquito,” Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.ady4515