Artificial Light at Night Is Quietly Extending Pollen Seasons and Increasing Allergy Risks in Cities

Artificial light at night is something most of us associate with streetlights, illuminated buildings, and glowing skylines. But new research suggests it may be doing far more than lighting our evenings. According to a recent study published in PNAS Nexus, exposure to artificial light after sunset is extending pollen seasons and raising allergen exposure in cities across the Northeastern United States. This finding adds a new and often overlooked factor to the growing list of environmental drivers affecting seasonal allergies.

A Closer Look at the Research

The study was led by Lin Meng and colleagues, who examined how nighttime light pollution interacts with plant biology and airborne pollen. To do this, the researchers analyzed 12 years of pollen data collected from 12 monitoring stations spread across the Northeastern United States. These stations provided detailed records of pollen concentrations over time, allowing the team to identify trends in pollen season timing and intensity.

What made this study especially robust was its integration of multiple data sources. The researchers combined pollen records with satellite-based measurements of artificial light at night as well as local climate data, including temperature and precipitation. This approach allowed them to isolate the effects of artificial light from other well-known drivers of pollen changes, such as warming temperatures or rainfall patterns.

Earlier Starts, Later Endings, Longer Seasons

The results were striking. Areas with higher exposure to artificial light at night experienced earlier starts to pollen seasons, later endings, and longer overall durations. Even after accounting for climate variables, artificial light remained a significant predictor of these changes.

Interestingly, the study found that the influence of nighttime lighting was stronger on the end of the pollen season than on the beginning. In other words, artificial light appears to be especially effective at delaying the natural shutdown of pollen production in the fall, rather than dramatically accelerating its start in spring.

This matters because pollen season length is directly tied to how long people are exposed to allergens. A longer season means more cumulative exposure, even if daily pollen levels remain the same.

More Days of Severe Allergen Exposure

Beyond timing, the study also examined the intensity of allergen exposure. The findings showed a clear difference between areas with and without significant artificial light at night.

In locations exposed to artificial light, 27% of pollen season days were classified as having severe allergen levels. In contrast, areas without substantial nighttime lighting saw severe levels on only 17% of pollen season days. That gap translates into many more high-risk days for people with allergies, asthma, or other respiratory sensitivities.

This suggests that artificial light doesn’t just stretch the season; it also amplifies the health burden by increasing the number of days when pollen concentrations are particularly high.

Why Light at Night Affects Plants

Plants rely heavily on natural light–dark cycles, known as photoperiods, to regulate their growth and reproduction. These cycles help plants determine when to flower, release pollen, and eventually enter dormancy as seasons change.

Artificial light at night disrupts these cues. When plants are exposed to streetlights or other sources of nighttime illumination, they may interpret the environment as having longer days than it actually does. This can delay key seasonal transitions, such as autumn leaf senescence, when trees normally lose their leaves and reduce biological activity.

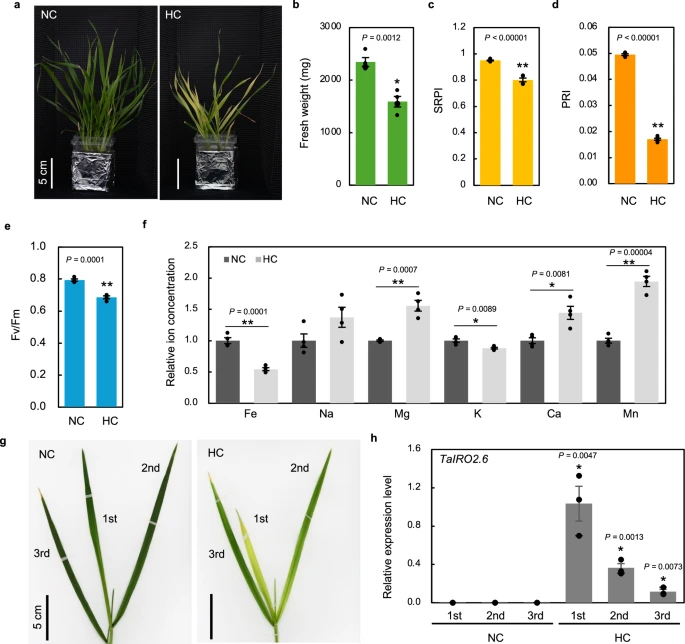

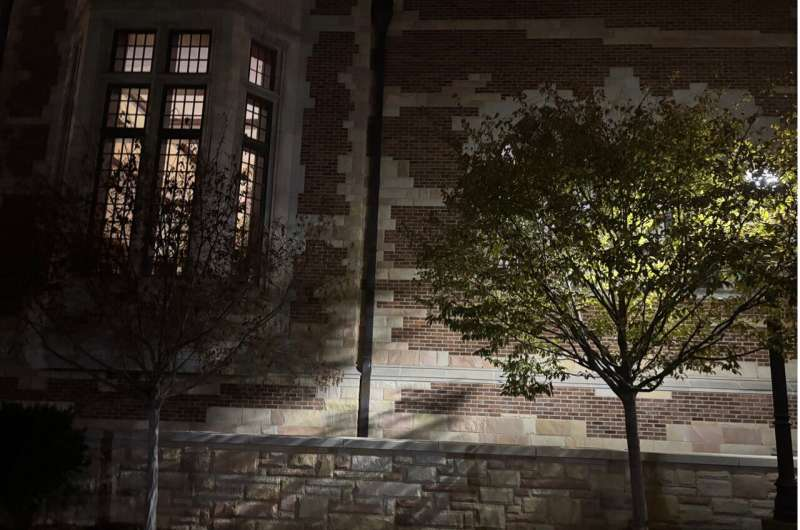

The study included visual evidence of this effect, showing two nearby trees exposed to different lighting conditions. The tree under a streetlight retained green leaves far later into the season than a neighboring tree growing in darkness. This same biological delay appears to extend to pollen production, keeping allergen levels elevated for longer periods.

An Overlooked Public Health Factor

Seasonal allergies already affect millions of people and place a significant burden on healthcare systems. The researchers argue that artificial light at night should be recognized as an overlooked driver of allergy risk, particularly in urban environments where light pollution is widespread.

Cities often experience a double impact: higher levels of artificial light and higher population density. When combined with existing challenges like air pollution and climate warming, extended pollen seasons can worsen symptoms and reduce quality of life for many residents.

The study suggests that urban planning and public health strategies should begin factoring in nighttime light exposure alongside more familiar environmental variables. This could include smarter lighting design, reduced unnecessary illumination, and greater awareness of how light pollution affects both ecosystems and human health.

How This Fits Into Broader Environmental Trends

The findings align with a growing body of research showing that artificial light at night alters natural rhythms across ecosystems. Previous studies have demonstrated that nighttime lighting can shift plant growing seasons, disrupt insect behavior, and interfere with animal circadian rhythms.

What makes this research stand out is its direct link between artificial light and measurable human health outcomes, specifically allergen exposure. It reinforces the idea that light pollution is not just an aesthetic or astronomical issue, but a biological and environmental one with real-world consequences.

Why the Northeastern United States Matters

The Northeastern United States is a particularly relevant region for this type of study. It includes many large, densely populated cities with significant nighttime lighting, as well as well-established pollen monitoring networks. The combination of long-term data availability and diverse urban–rural gradients made it an ideal setting to detect the effects of artificial light.

While the study focused on this region, the authors suggest that similar patterns may exist elsewhere, especially in other highly urbanized areas. This raises important questions about how global increases in light pollution could influence allergy trends worldwide.

What This Means Going Forward

As cities continue to grow and nighttime illumination becomes more widespread, understanding its unintended effects will be increasingly important. Artificial light at night now joins climate change, air pollution, and land use as a factor shaping pollen seasons and allergy risk.

For individuals, this research may help explain why allergy symptoms seem to last longer than they used to. For policymakers and urban planners, it offers new evidence that how we light our cities matters, not just for energy use or visibility, but for environmental and public health as well.

Reducing unnecessary nighttime lighting won’t eliminate seasonal allergies, but it could become part of a broader strategy to limit their duration and severity. As this study shows, sometimes the smallest environmental changes can have surprisingly large biological effects.

Research paper: https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/5/1/pgaf405