Biology-Inspired Brain Model Matches Animal Learning and Uncovers Overlooked Neuron Activity

Scientists have built a new biology-inspired computational brain model that behaves strikingly like a real animal brain while learning. What makes this research especially compelling is that the model not only matched animal learning performance almost exactly, but also led researchers to uncover a previously unnoticed group of neurons in real animal data—neurons linked to making mistakes rather than correct decisions.

The study was carried out by researchers from Dartmouth College, MIT, and the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and the findings were published in Nature Communications in 2025. Unlike many artificial intelligence systems that rely heavily on large training datasets, this model was built from the ground up to reflect how real neurons connect, communicate, and organize into brain circuits.

A Brain Model Built on Biology, Not Data

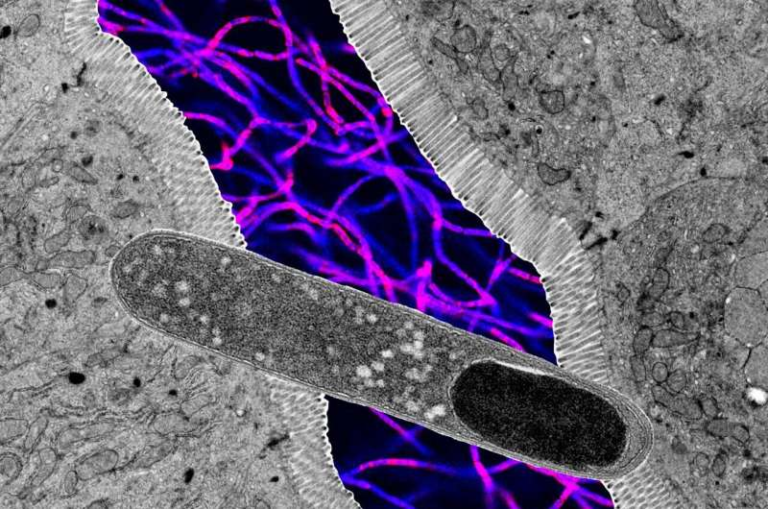

Most computational brain models simplify the brain or focus on only one scale of activity—either individual neurons or large brain regions. This new model takes a very different approach. It was designed to faithfully replicate both microscopic and large-scale features of real brains.

At the smallest level, the model simulates how individual neurons interact through electrical signals and chemical neurotransmitters, following known biological principles. At the larger scale, it models interactions between key brain regions involved in learning and decision-making.

Importantly, the model was never trained using animal experiment data. Instead, it was built purely based on decades of neuroscience research about how brains are wired and how neurons behave. Only after the model was complete did the researchers ask it to perform the same learning task previously given to lab animals.

The results were unexpected. The model learned at nearly the same pace, made mistakes in similar patterns, and showed matching neural activity rhythms to those seen in animals.

The Learning Task That Revealed the Similarity

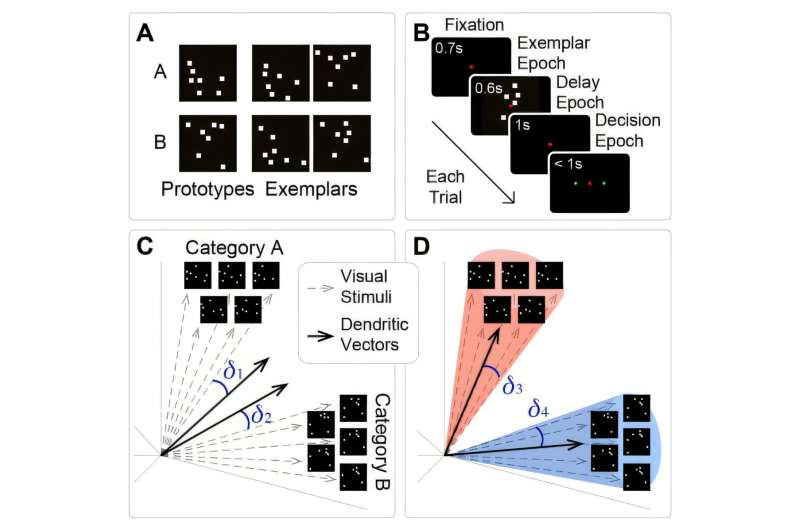

To test the model, researchers used a simple visual category learning task. Both animals and the computational model were shown patterns of dots and had to decide which of two broad categories the patterns belonged to.

Learning this task is not straightforward. Animals typically show uneven, erratic progress, sometimes improving, sometimes regressing, before eventually mastering the task. Remarkably, the model followed the same messy learning curve.

Even more striking was how closely the neural activity patterns matched. As learning progressed, both animals and the model showed increased synchronization between brain regions when making correct decisions.

Modeling the Brain at Multiple Scales

One of the most important aspects of this work is how the model bridges small and large scales of brain organization.

At the smallest level are what the researchers call “primitives.” These are tiny circuits made up of just a few neurons, designed to perform basic computations found in real brains. For example, one primitive in the model mimics a winner-takes-all circuit, where excitatory neurons compete with one another while inhibitory neurons suppress weaker signals. This kind of architecture is well-documented in real cortical tissue.

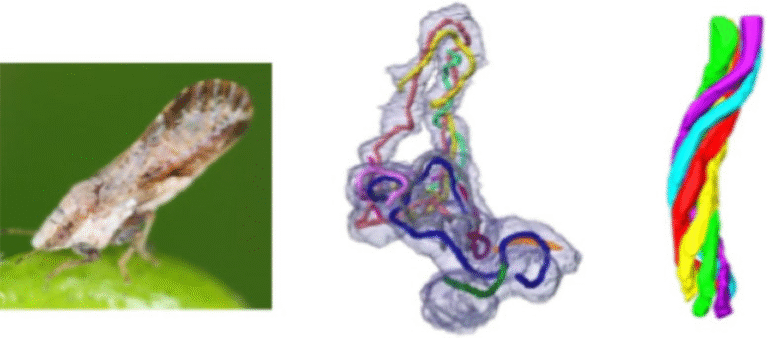

At the larger scale, the model includes four key brain regions essential for learning and memory:

- Cortex, responsible for processing sensory information

- Striatum, involved in action selection and habit formation

- Brainstem, contributing to basic control and modulation

- Tonically Active Neurons (TANs), which release acetylcholine and introduce variability into behavior

These regions interact dynamically, just as they do in real brains, allowing complex behaviors to emerge naturally from simple biological rules.

The Role of Neuromodulators Like Acetylcholine

Neuromodulators play a crucial role in learning, and this model captures that reality. Early in learning, acetylcholine released by TANs introduces “noise” into the system. This variability encourages exploration, allowing the model to try different actions rather than immediately locking into one strategy.

As learning improves, the cortex and striatum strengthen connections that suppress TAN activity, reducing randomness and allowing more consistent, confident decisions. This transition mirrors what neuroscientists have observed in animal brains during learning.

Realistic Brain Rhythms Emerge Naturally

As the model learned the task, researchers observed an increase in beta-frequency brain rhythms between the cortex and striatum. This synchronization occurred specifically during correct decisions.

This detail is significant because similar beta-band synchronization has been repeatedly observed in animal experiments. The fact that it emerged naturally in the model—without being explicitly programmed—suggests the system is capturing something fundamental about how real brains learn.

Discovering Neurons Linked to Errors

Perhaps the most surprising outcome of the study was the discovery of a group of neurons whose activity predicted mistakes rather than correct answers.

About 20% of neurons in the model behaved in a way that increased the likelihood of an incorrect decision. These neurons, described as “incongruent neurons,” initially seemed like a modeling error.

However, when researchers went back and reanalyzed existing animal brain recordings, they found the same pattern. The neurons were always there, but no one had previously examined their role in this way.

This discovery highlights one of the most powerful advantages of biologically grounded models: they can reveal patterns in experimental data that humans may overlook.

Why Error-Predicting Neurons May Matter

At first glance, neurons that promote mistakes might seem useless or even harmful. But neuroscientists suspect these neurons serve an important purpose.

In real-world environments, rules change. A brain that always rigidly follows learned patterns can struggle to adapt. Neurons that occasionally push the system toward alternative choices may help maintain flexibility and adaptability, allowing animals—and humans—to adjust when conditions shift.

Other recent studies have shown that both humans and animals sometimes deliberately explore less optimal choices, supporting the idea that these incongruent neurons play a functional role.

From Brain Science to Medical Applications

The researchers behind the study are not stopping here. Several team members have launched a company called Neuroblox.ai, aimed at turning this modeling approach into a platform for biomedical applications.

The long-term goal is to use biomimetic brain models to:

- Simulate neurological diseases

- Test drug effects earlier in development

- Explore how interventions alter brain dynamics

- Reduce the cost and risk of clinical trials

By experimenting on a realistic virtual brain first, researchers may be able to identify promising therapies faster and more safely.

Why This Research Matters

This work represents a shift in how scientists think about artificial intelligence and brain modeling. Instead of focusing purely on performance, it emphasizes biological realism and mechanistic understanding.

The fact that a model built purely from biological principles can predict real neural behavior and even guide new discoveries in experimental data suggests a powerful future for this approach.

As the model continues to expand—adding more brain regions, neuromodulators, and tasks—it could become an essential tool for both neuroscience research and medical innovation.

Research Paper:

Anand Pathak et al., Biomimetic model of corticostriatal micro-assemblies discovers a neural code, Nature Communications (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67076-x