Cat Coronavirus Disease Is Forcing Scientists to Rethink How Coronaviruses Behave in the Immune System

Researchers at the University of California, Davis, have uncovered new findings about a serious cat disease that are reshaping long-held scientific assumptions about how coronaviruses interact with the immune system. The disease, known as feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), was once considered almost universally fatal. Now, not only is it becoming treatable, but it is also offering valuable clues about long-term coronavirus infections that may extend far beyond veterinary medicine.

FIP is caused by a mutated form of feline coronavirus, a virus that is extremely common among cats worldwide. In most cases, feline coronavirus causes mild intestinal symptoms or no symptoms at all. However, in a small percentage of cats, the virus mutates inside the body and becomes capable of triggering a severe, body-wide inflammatory disease. When this happens, the result is FIP—a condition that can damage multiple organs and lead to death if left untreated.

What makes this new research especially important is that it challenges a core belief scientists have held for decades about how the virus spreads inside the body.

A Major Shift in Understanding How FIP Spreads

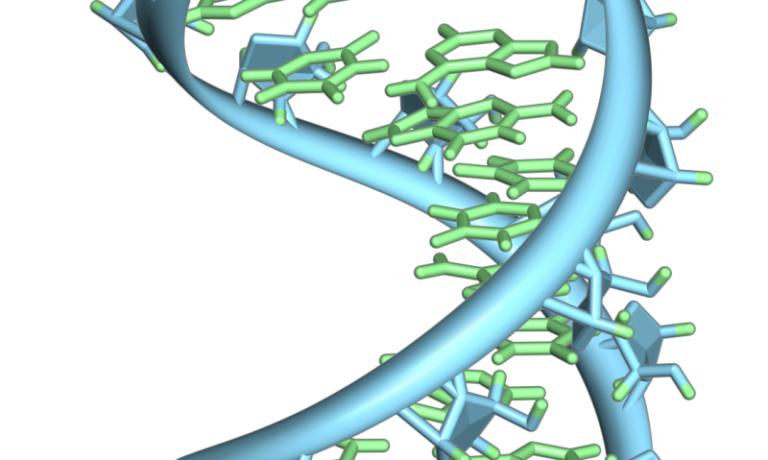

For many years, scientists believed that the virus responsible for FIP infected only one specific type of immune cell, known as macrophages. Macrophages act as scavengers in the immune system, engulfing pathogens and debris. This limited view shaped how researchers understood disease progression and immune dysfunction in FIP.

The UC Davis team, led by associate professor Amir Kol at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, found something very different.

Their research shows that the virus does not limit itself to macrophages. Instead, it infects a much broader range of immune cells, including B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes. These cells are central players in immune defense. B cells produce antibodies, while T cells help coordinate immune responses and destroy infected cells. When these critical cells become infected, the immune system’s ability to protect the body can be deeply compromised.

This discovery fundamentally changes how scientists understand FIP and raises new questions about coronavirus behavior in general.

Inside the Immune System’s Control Centers

To reach these conclusions, researchers examined lymph node samples from cats with naturally occurring FIP. Lymph nodes are essential hubs of immune activity, where immune cells gather, communicate, and organize responses to infection.

Within these lymph nodes, the team detected viral material inside multiple immune cell types, not just macrophages. Even more importantly, they found evidence that the virus was actively replicating inside these cells. This means the virus was not simply leaving behind inactive fragments but was continuing to reproduce and potentially spread further through the immune system.

This active replication inside B and T lymphocytes suggests a far more aggressive and systemic infection than previously assumed.

Why These Findings Matter Beyond Cats

Although FIP affects only cats, its similarities to serious coronavirus-related illnesses in humans make it particularly relevant. Like severe COVID-19 or long COVID, FIP involves widespread inflammation, immune system disruption, and symptoms that can persist, disappear, and later return.

In humans, scientists suspect that coronaviruses may persist in the body or continue interfering with immune function long after the initial infection appears to be over. However, studying this directly is extremely difficult. Doctors rarely have access to immune tissues such as lymph nodes in living patients, especially over long periods of time.

Cats with FIP offer a rare and valuable opportunity. Because the disease occurs naturally and affects immune tissues directly, researchers can study infected lymph nodes and immune cells in ways that are simply not possible in human patients.

Viral Persistence Even After Treatment

Another striking discovery from the study is that viral traces can remain in immune cells even after antiviral treatment ends and cats appear clinically healthy. This suggests that the virus may persist silently within long-lived immune cells.

Some immune cells, particularly memory B and T cells, can survive in the body for years. If these cells harbor remnants of the virus, they could potentially contribute to lingering immune dysfunction or disease relapse later on.

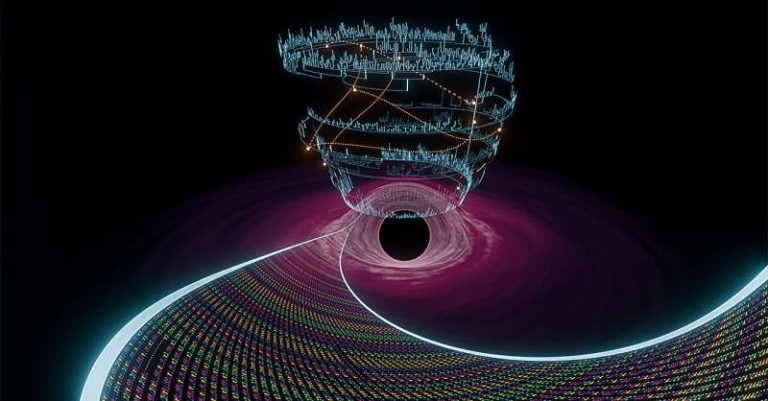

This finding adds weight to the idea that coronaviruses may establish long-term reservoirs inside the immune system, rather than being completely eliminated once symptoms resolve.

A Real-World Model for Long-Term Coronavirus Disease

The researchers propose that FIP could serve as a powerful real-world model for studying long-term coronavirus infections. Unlike laboratory models that rely on artificial infection, FIP develops naturally and mirrors many features of chronic or severe viral disease in humans.

By studying how feline coronavirus spreads, persists, and disrupts immune function over time, scientists may gain insights into broader questions surrounding post-viral syndromes, chronic inflammation, and immune exhaustion.

This research highlights the growing importance of comparative medicine, where insights from animal health help inform human medical research. The boundaries between veterinary and human medicine continue to blur, especially when it comes to infectious diseases.

Advances in Treating FIP

For decades, a diagnosis of FIP was considered a death sentence. In recent years, however, antiviral treatments such as GS-441524 have dramatically changed outcomes. Cats that once would have died within weeks are now surviving and returning to normal lives.

One such example is Lychee, a domestic long-hair cat who participated in a clinical trial at UC Davis and was successfully cured of FIP. While these treatments are not yet universally accessible or officially approved everywhere, they represent a major breakthrough in veterinary medicine.

The new findings may help refine future therapies by identifying which immune cells need to be targeted to fully eliminate the virus and prevent relapse.

Understanding Feline Infectious Peritonitis More Broadly

FIP generally appears in two main forms. The wet (effusive) form causes fluid accumulation in the abdomen or chest, leading to rapid deterioration. The dry (non-effusive) form causes inflammatory lesions in organs such as the liver, kidneys, brain, or eyes, often resulting in more subtle but persistent symptoms.

Both forms reflect a failure of the immune system to control the mutated virus. The discovery that the virus infects immune cells directly helps explain why the immune response becomes so destructive rather than protective.

A Broader Scientific Impact

This study underscores how much there is still to learn about coronaviruses, even years after the global COVID-19 pandemic brought them into intense focus. The idea that coronaviruses can infect and persist within multiple immune cell types may have implications well beyond FIP.

As researchers continue to investigate long COVID and other chronic inflammatory conditions, lessons from veterinary medicine may play a surprisingly central role.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2025.110864