Cells Use Morse Code-Like Rhythms to Coordinate Growth

Cells are constantly exposed to changing conditions. Lack of food, excess salt, or high temperatures all place stress on living organisms, and survival depends on how well cells sense these changes and respond. A new study from researchers at AMOLF in the Netherlands reveals that cells don’t just react in a simple on-off manner. Instead, they use precise rhythmic patterns, similar to Morse code, to coordinate growth and stress responses across the entire body.

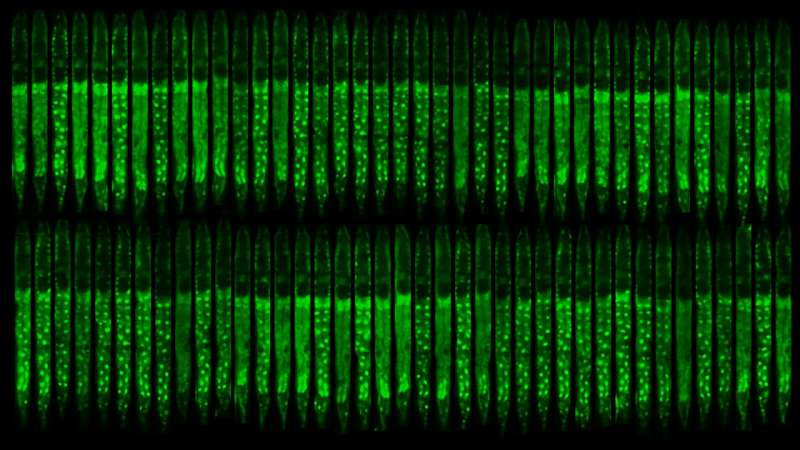

This research focuses on the tiny roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, a widely used model organism in biology. Despite its simplicity, this worm shares many fundamental biological mechanisms with humans, making it a powerful system for understanding processes linked to growth, metabolism, aging, cancer, and diabetes.

How cells respond to stress through insulin signaling

In both worms and humans, insulin signaling plays a central role in how cells respond to stress. When conditions are favorable, insulin pathways promote growth and development. Under stress, however, these signals change, triggering protective responses instead.

In C. elegans, insulin signaling controls a protein called DAF-16, which is the worm equivalent of the human FOXO transcription factors. When insulin signaling is high, DAF-16 remains outside the cell nucleus in the cytoplasm. When insulin signaling drops—such as during starvation or environmental stress—DAF-16 moves into the nucleus, where it switches on genes that help the organism cope with stress.

What makes this new study remarkable is not just that DAF-16 enters the nucleus, but how and when it does so.

A surprising discovery under the microscope

The discovery began somewhat by chance. Guest researcher Maria Olmedo from the University of Seville brought a strain of C. elegans in which DAF-16 was fluorescently labeled, allowing researchers to observe its movements in living animals. Along with former AMOLF Ph.D. student Olga Filina, she noticed something unexpected while watching the worms under the microscope.

Instead of DAF-16 moving independently in different cells, it entered and exited the nucleus at the same time in virtually all cells of the body. Muscle cells, intestinal cells, and other tissues all showed synchronized behavior, as if the entire organism was following a shared internal clock.

This synchronization alone was surprising, but the researchers soon realized there was more to the pattern.

Rhythms that carry information

DAF-16 did not simply move into the nucleus and stay there. Under constant stress, it moved in and out repeatedly, creating pulses over time. These pulses formed distinct rhythms, and crucially, different types of stress produced different rhythmic patterns.

For example:

- Starvation led to relatively regular, repeating oscillations.

- Salt stress caused more irregular pulses, with the frequency increasing as salt levels rose.

The researchers concluded that cells use these rhythmic patterns to encode information, much like Morse code uses dots and dashes to transmit messages. In this case, the frequency and duration of DAF-16 nuclear pulses convey information about the type and intensity of stress the organism is experiencing.

Why synchronization across the whole body matters

AMOLF Ph.D. student Burak Demirbas, who later joined the University of Amsterdam, decided to investigate what these rhythms actually do for the worm. His experiments revealed a clear and direct link between DAF-16 rhythms and body growth.

When DAF-16 entered the nucleus, larval growth stopped. When it exited the nucleus, growth resumed. This relationship was consistent and repeatable, showing that the rhythmic nuclear localization of DAF-16 actively controls whether the worm grows or pauses development.

This finding helps explain why synchronization across all cells is so important. If different parts of the body responded at different times, the worm would grow unevenly, disrupting its overall structure. By keeping all cells in sync, the organism ensures that growth and arrest happen simultaneously across the entire body, preserving proper proportions and function.

From worms to humans: why this matters

Although this study was done in worms, its implications extend far beyond C. elegans. The protein DAF-16 belongs to the FOXO family, which is highly conserved in humans and other animals. Human FOXO proteins play key roles in:

- Regulating tissue and organ growth

- Responding to metabolic and environmental stress

- Protecting cells from damage

- Influencing aging and lifespan

FOXO proteins are also deeply involved in diabetes, cancer, and age-related diseases, where insulin signaling is often disrupted. The discovery that FOXO activity can be regulated through rhythmic nuclear pulses, rather than simple activation or inhibition, opens new ways of thinking about how these pathways function in complex organisms.

Rhythmic signaling as a broader biological principle

This study adds to a growing body of research showing that timing and rhythm are critical in cell signaling. Many biological systems rely on oscillations rather than constant signals. Examples include:

- Calcium waves in neurons

- Circadian rhythms controlling sleep and metabolism

- Pulsed hormone release in the endocrine system

In each case, the pattern of the signal carries as much information as the signal itself. The findings from AMOLF suggest that insulin signaling and FOXO activity should be viewed in the same way—not as static switches, but as dynamic processes that encode information over time.

The experimental approach behind the discovery

The researchers combined advanced live-cell microscopy with careful quantitative analysis. By imaging fluorescent DAF-16 in living worms over extended periods, they were able to track nuclear localization events with high temporal precision. This allowed them to identify synchronization across tissues and measure pulse frequency and duration under different stress conditions.

Importantly, the study also showed that disrupting DAF-16 interferes with proper growth control, confirming that these rhythms are not just a byproduct of stress but a functional regulatory mechanism.

Looking ahead

The researchers believe that many unanswered questions remain. How exactly do cells synchronize these pulses across the entire body? What molecular signals coordinate timing between tissues? And do similar rhythmic mechanisms operate in mammals, including humans?

As research continues, understanding these rhythmic signaling patterns could provide new insights into how organisms balance growth and survival—and how this balance breaks down in disease.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66164-2