Cellular Crowding in Fruit Fly Embryos Sparks a Major DNA Reorganization During Early Development

Fruit fly embryos move through their earliest hours of life at incredible speed. Right after fertilization, they undergo a rapid series of nuclear divisions—thirteen rounds in total—without forming individual cells. During this time, the embryo relies entirely on maternal proteins that were packed into the egg long before fertilization. Only after these initial rapid cycles does the embryo begin taking charge of its own development by turning on its own genes.

A new study published in EMBO Reports explores a long-standing biological mystery: How does an embryo know when it’s time to shift from maternal control to its own genetic program? Researchers at Dartmouth College have uncovered a mechanism that links this transition to nuclear crowding—specifically, the increasing nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio as more and more nuclei pack into the same shared cytoplasm.

This discovery helps explain a fundamental process not just in fruit flies, but potentially in many animals, including humans. It also offers insights into conditions like cancer and aging, where this ratio is known to go awry.

What Exactly Changes Inside the Embryo?

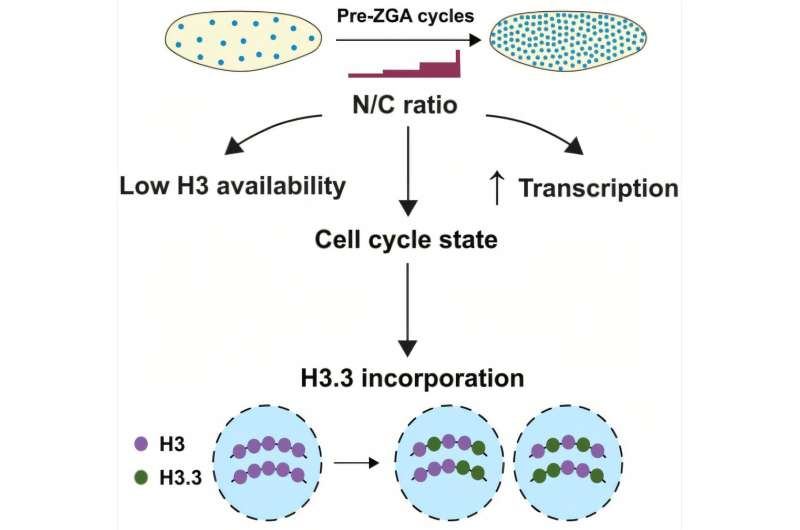

The study shows that as the embryo races through nuclear division cycles, the same cytoplasmic space begins holding thousands of nuclei. By the 13th division, that space has gone from containing one nucleus to over 6,000. This dramatic change in density provides a biochemical signal that the embryo is ready for the next developmental stage.

The key player in this shift is the structure of DNA itself—specifically, histones, the proteins DNA wraps around. These proteins help organize, compact, and protect DNA. Two forms of histone H3 exist in fruit fly embryos: H3, used primarily during DNA replication, and H3.3, a variant associated with gene activation.

Researchers found that as the embryo becomes more crowded with nuclei, the DNA begins replacing H3 with H3.3, even though the two proteins differ by only four amino acids. That tiny difference is enough to give H3.3 a very different function, and its incorporation represents a crucial step toward the embryo activating its own genome.

Tracking H3 and H3.3 in Real Time

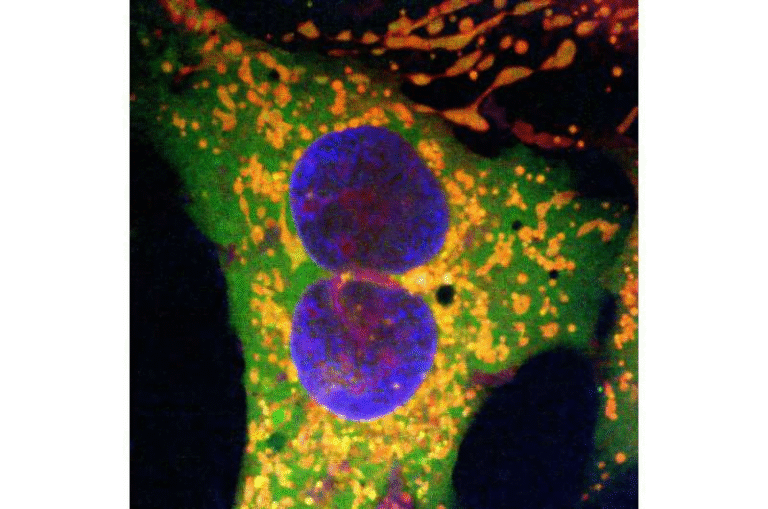

To explore how these histones behave during early development, the researchers used fluorescent tagging to label H3 and H3.3. This allowed them to watch how each protein entered and left the nuclei over multiple rounds of nuclear division.

Their observations revealed a clear pattern:

- The amount of H3 bound to DNA drops with every division cycle.

- Meanwhile, the incorporation of H3.3 consistently rises.

This shift doesn’t happen randomly. It correlates tightly with the embryo’s nuclear crowding levels. When nuclei were evenly distributed throughout the embryo, the switch happened uniformly. But when the researchers examined embryos with mutations that prevented nuclei from spreading out evenly, the results became even more striking. Crowded regions reliably showed higher levels of H3.3, while sparsely populated regions did not.

This demonstrated two important points:

- The switch from H3 to H3.3 is location-specific, happening more in dense nuclear areas.

- It is not triggered by transcription, because the switch still occurred even before the embryo began making its own RNA.

Why the Nuclear-to-Cytoplasmic Ratio Matters

Scientists have long suspected that embryos use their changing nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio as a developmental timer. In earlier studies, the same Dartmouth lab showed that once the embryo’s DNA content reaches a critical threshold, it triggers a slowdown in the cell cycle and initiates the activation of the embryo’s own genome. This new work directly links that ratio to DNA repackaging, providing a concrete molecular explanation.

Specifically, the study concludes that when the nuclei become sufficiently crowded, the cell cycle enters a different state—no longer dominated by rapid replication—and this new state favors H3.3 deposition. Since H3.3 is associated with open, active chromatin, this shift helps prepare the genome for transcription.

What Is Special About H3.3?

Histone variants are a fascinating part of DNA packaging, and H3.3 is a particularly important one. While canonical H3 is deposited during DNA replication, H3.3 gets inserted into DNA independently of replication, often in regions that remain transcriptionally active. This makes it central to processes like memory formation, stem cell identity, and cellular reprogramming.

Even in adult cells, the balance between H3 and H3.3 is critical. Disturbances in histone composition can lead to diseases, including certain cancers linked to histone mutations (known as oncohistones).

In the embryo, the shift toward H3.3 marks the moment when the genome becomes ready for widespread transcription. Without this shift, the embryo would not be able to move into the next phase of development.

How the Researchers Tested Histone Function

To determine what caused the difference between H3 and H3.3, the scientists created chimeric histones—proteins that combined parts of each histone type. This experiment revealed that the crucial difference lies in the chaperone-binding domain, a region of the protein that interacts with other proteins responsible for shuttling histones onto DNA.

The gene structure itself—promoters, introns, untranslated regions—did not influence whether a histone behaved like H3 or H3.3. This clarified that the embryo’s histone switch depends on protein function, not on where the histone gene sits in the genome.

Drosophila as a Favorite Model Organism

Fruit flies have long been a go-to model for studying developmental biology. Their embryos develop inside a transparent eggshell, making them perfect for imaging. They also develop incredibly fast, hatching in just 24 hours.

Beyond convenience, fruit flies have played a major role in discoveries that later turned out to apply to humans. Everything from our understanding of chromosomes to genes controlling body patterning has roots in Drosophila research. This new study follows that tradition, uncovering a mechanism that could extend far beyond insects.

Why This Research Matters Beyond Fruit Flies

The researchers emphasize that disruptions in the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio are not limited to embryos. Conditions like cancer, premature aging, and other diseases often show abnormal nuclear sizes or chromatin organization.

Since the study links developmental timing to chromatin state and nuclear crowding, it may spark new research into how aberrant nuclear structure affects gene regulation in disease.

In addition, the findings could help scientists studying early development in other animals, including vertebrates. The concept of an N/C ratio acting as a developmental trigger appears in frogs, zebrafish, and possibly mammals. Understanding the molecular details behind that trigger—especially the role of H3.3—could be key to understanding how embryos across species coordinate major developmental transitions.

What Comes Next?

The Dartmouth team plans to investigate exactly where in the genome H3.3 is incorporated during the early nuclear cycles. Identifying which genes receive H3.3 first may help uncover the earliest steps of zygotic genome activation and how embryos decide which genetic programs to turn on.

The study also highlights the contributions of undergraduate researchers and graduate students in the lab, reflecting how collaborative and hands-on developmental biology research can be.

Reference

Local nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio regulates H3.3 incorporation via cell cycle state during zygotic genome activation

https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s44319-025-00596-1