Cellular Nanodomains Inside Biomolecular Condensates Reveal New Clues About ALS and Dementia

Researchers have uncovered an intriguing layer of organization inside the cell that may reshape how we understand neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and frontotemporal dementia. A team from the University of Michigan has identified tiny regions—called nanodomains—within biomolecular condensates that appear to influence how proteins and RNA behave as these droplets form, age, and potentially contribute to disease. This discovery shines a new light on long-standing questions about why certain proteins clump together in harmful ways in neurodegeneration and how current ALS drugs may work at the molecular level.

Biomolecular condensates are important hubs in cells. They gather together proteins and RNA molecules to regulate essential processes such as cell division, stress response, and gene expression. These condensates don’t have membranes like organelles do. Instead, they form through liquid–liquid phase separation, which works somewhat like the formation of droplets in the atmosphere. Because they lack a rigid structure and move around easily, scientists have had a difficult time examining what happens inside them on a molecular scale.

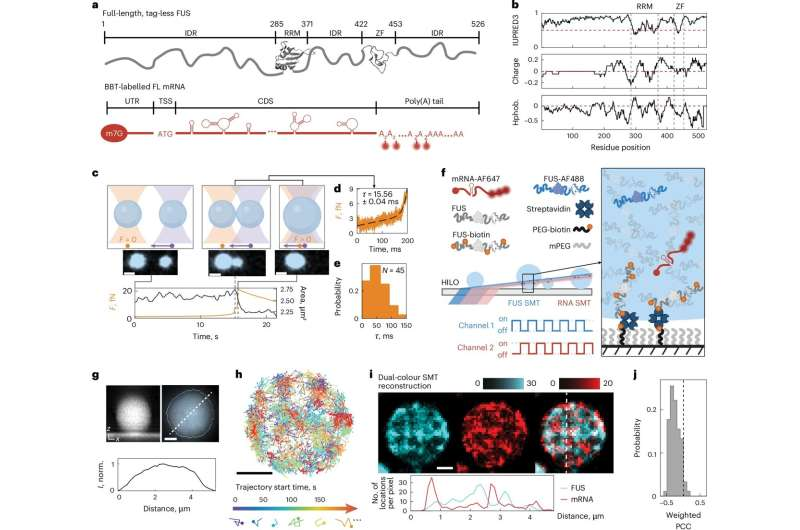

The new study zeroed in on a protein called FUS (fused-in-sarcoma), a key regulator of RNA metabolism that is heavily linked to ALS and dementia when mutated. Under certain stress conditions, cells undergo something known as hyposmotic phase separation, where a rise in salt concentration causes the cell to lose water and shrink by nearly 50%. During this process, FUS condenses into droplets that help the cell adapt. However, in disease states, mutant FUS accumulates in the cytoplasm, condenses abnormally, and gradually forms harmful aggregates. Understanding how this transition happens has remained one of the toughest challenges in ALS research.

To study these condensates in controlled conditions, the researchers purified full-length FUS and modified it by attaching a removable sugar group. This sugar temporarily blocked condensation, allowing the team to trigger droplet formation at precise moments. They also fluorescently labeled both FUS proteins and RNA probes with distinct colors, making it possible to track individual molecules inside the droplets using advanced fluorescence microscopy.

One of the biggest experimental problems was that these droplets move, roll, and wobble on microscope slides. If the droplet shifts even slightly, single-particle tracking becomes inaccurate. The team solved this by tethering the droplets to a surface using just enough anchors to keep them still, without squashing them flat. With the droplets immobilized, they used HILO microscopy, a technique that allows sensitive tracking of single molecules, to watch what was happening inside.

What they found was unexpected: the movement of molecules inside the condensates was not uniform. Instead, RNA and protein motion slowed dramatically within tiny, highly concentrated regions—these newly identified nanodomains. These nanodomains function like molecular traps, altering how long different molecules remain in specific locations. As the condensates aged, the nanodomains gradually migrated toward the surface of the droplet. This subtle shift in internal architecture may play a role in how condensates transition from fluid, reversible states into more solid, potentially harmful structures.

Importantly, the researchers were able to watch fibrils—rigid protein structures associated with neurodegenerative disease—form around the edges of these droplets. The nanodomains seemed to act as seeds for fibril formation once they reached the outer boundary. This observation aligns with long-held theories that certain disease-causing protein aggregates originate from phase-separated condensates.

The team also tested two widely used ALS drugs, edaravone and riluzole, to see how they influenced condensate behavior. Surprisingly, both drugs accelerated the movement of nanodomains to the condensate surface and sped up the growth of fibrils. While fibrils are often seen as toxic, some researchers believe they may actually serve a protective function, acting like molecular sponges that draw in smaller, more harmful aggregates. If so, this accelerated fibril formation could represent an additional, previously unknown mechanism through which these drugs offer therapeutic benefit.

This research contributes to a rapidly expanding field focused on the biology of phase separation. Many cellular processes depend on condensates to concentrate molecules, accelerate reactions, or isolate harmful substances. Condensates have been implicated in cancer, viral infections, and a broad range of neurodegenerative diseases. Understanding how internal structures like nanodomains form and behave may open the door to new therapeutic strategies—such as chemically tuning condensates to prevent harmful aggregation, enhance beneficial sequestration, or even serve as targeted drug-delivery reservoirs.

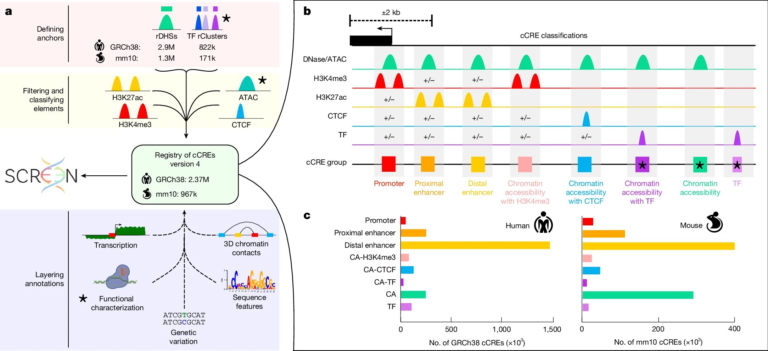

To put this discovery in context, it helps to understand more broadly how biomolecular condensates function in cells. These droplets appear in diverse cellular locations, including the nucleus and cytoplasm. They help regulate transcription, RNA splicing, protein quality control, and stress granule formation. Their ability to assemble and disassemble quickly allows the cell to respond to stresses and environmental changes with remarkable speed.

The concept of condensate aging is particularly important. A young condensate behaves like a liquid—molecules flow freely inside it. As the condensate matures, interactions between proteins can become stronger, leading to a more gel-like or even solid-like state. This transition is thought to contribute to disorders such as ALS, where proteins that normally remain fluid become trapped in irreversible aggregates. Nanodomains may be the structural intermediates that control whether a condensate stays flexible or hardens into pathological fibrils.

FUS is just one example of a protein that undergoes phase separation. Others include TDP-43, hnRNPA1, and many RNA-binding proteins. Mutations in these proteins often disrupt their ability to maintain healthy phase transitions. In ALS, the presence of mislocalized FUS in the cytoplasm is a major biomarker of disease. The new findings suggest that the earliest steps toward FUS aggregation happen within condensates themselves, long before visible clumps appear.

Another interesting aspect of this research is the method itself. Single-molecule tracking inside condensates has historically been extremely challenging. The tether-and-track approach developed here could be used to study many different proteins and diseases. It offers a window into nanoscale processes that were previously invisible.

For readers who are curious about the bigger picture: neurodegenerative diseases often involve a breakdown in how cells handle protein folding, stress responses, and molecular organization. The study of biomolecular condensates offers a unifying framework that ties these issues together. Phase separation provides a natural mechanism for cells to sort and regulate complex biochemical networks. But when this system fails, the consequences can be severe.

This new work gives researchers a clearer map of what goes wrong inside condensates linked to ALS. By identifying nanodomains, understanding how they migrate, and observing how drugs influence them, scientists are one step closer to decoding the molecular origins of neurodegeneration and developing more targeted treatments.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41565-025-02077-x