CRISPR Discovery Could Lead to a Single Diagnostic Test for COVID, Flu, and RSV

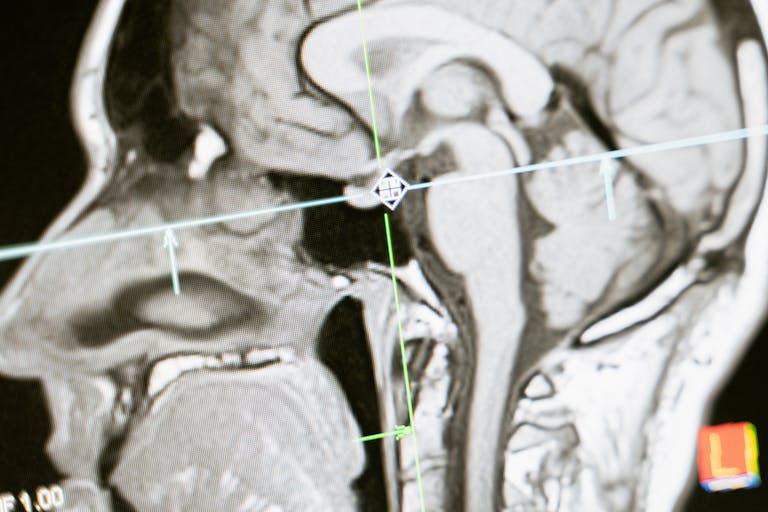

Researchers have uncovered a previously unknown function of a CRISPR immune system that could significantly change how viral infections like COVID-19, influenza, and RSV are detected. The discovery centers on a lesser-known CRISPR system called Cas12a3, and it opens the door to creating one rapid diagnostic test capable of identifying multiple respiratory viruses at once.

The findings come from a collaborative international research effort led in part by scientists at Utah State University (USU) and were published in the journal Nature. Beyond diagnostics, the work also deepens scientific understanding of how bacteria defend themselves against viral threats and how those mechanisms might be adapted for medical use.

Understanding CRISPR as an Immune System

CRISPR, short for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, is best known for its role in gene editing. However, long before it became a laboratory tool, CRISPR evolved as a natural immune defense in bacteria. Its job is to recognize invading viruses, such as bacteriophages, and stop them from replicating.

Most CRISPR systems work by targeting DNA, cutting it into pieces so the virus can no longer function. The widely known CRISPR-Cas9 system operates this way and has become a cornerstone of modern genetic research.

What makes this new discovery so important is that Cas12a3 works differently.

Cas12a2 and Cas12a3: Similar but Critically Different

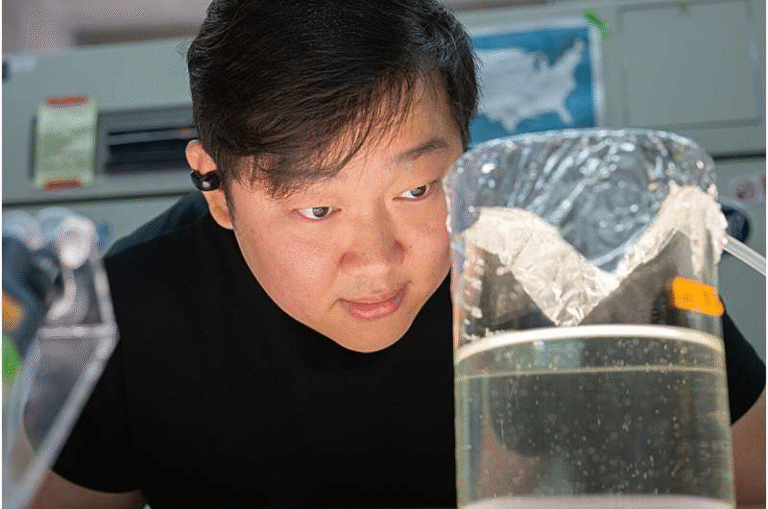

The USU research team, led by chemist Ryan Jackson, has been studying two relatively obscure CRISPR systems known as Cas12a2 and Cas12a3. Unlike Cas9, both of these systems are RNA-targeting CRISPR effectors, meaning they respond to RNA instead of DNA.

While Cas12a2 and Cas12a3 may sound similar, their behavior inside cells is strikingly different.

Cas12a2, when activated by viral RNA, begins indiscriminately cutting DNA. This effectively destroys viral genetic material, but it also damages the host cell’s DNA in the process, often killing the cell entirely.

Cas12a3, on the other hand, takes a far more precise and controlled approach.

A Newly Discovered Way to Stop Viruses

The key discovery is that Cas12a3 targets transfer RNA (tRNA) rather than DNA. tRNA plays a central role in protein production, acting as a molecular translator that helps cells turn genetic instructions into functional proteins.

Cas12a3 works by cleaving the tail of tRNA, a small region responsible for carrying amino acids during protein synthesis. By removing this tail, the tRNA can no longer function properly, and protein production comes to a halt.

This is a powerful antiviral strategy. Viruses rely entirely on a host cell’s protein-making machinery to reproduce. By shutting down protein synthesis, Cas12a3 effectively stops viral replication, while leaving the host cell’s DNA untouched.

This mechanism represents a newly identified CRISPR immune response, one that had not been documented before.

Why Targeting tRNA Is a Big Deal

tRNA is often described as the lynchpin of protein synthesis, and disrupting it has immediate consequences for any virus trying to hijack a cell. What makes Cas12a3 especially intriguing is its ability to target tRNA with remarkable specificity, avoiding the widespread collateral damage seen with other CRISPR systems.

This precision suggests that Cas12a3 could be safer to adapt for medical applications, including diagnostics and potentially future therapies.

The researchers believe this ability to stop pathogens while preserving the integrity of the host genome could represent a major breakthrough in CRISPR biology.

Implications for Rapid Viral Diagnostics

One of the most exciting outcomes of this research is its potential use in next-generation diagnostic tests.

Current rapid tests for respiratory illnesses often focus on detecting a single virus. If a patient wants to know whether they have COVID-19, influenza, or RSV, they may need multiple tests, each designed for a specific pathogen.

Cas12a3 could change that.

Because the system is activated by viral RNA, scientists can program it to respond to different viral sequences. Once activated, Cas12a3 can cleave specially designed synthetic tRNA reporters, producing a detectable signal.

This means a single diagnostic platform could potentially:

- Detect multiple viruses at once

- Distinguish between COVID-19, flu, and RSV

- Deliver results quickly and accurately

Such a test would be especially valuable during respiratory virus season, when symptoms often overlap and rapid identification is critical.

A Global Scientific Collaboration

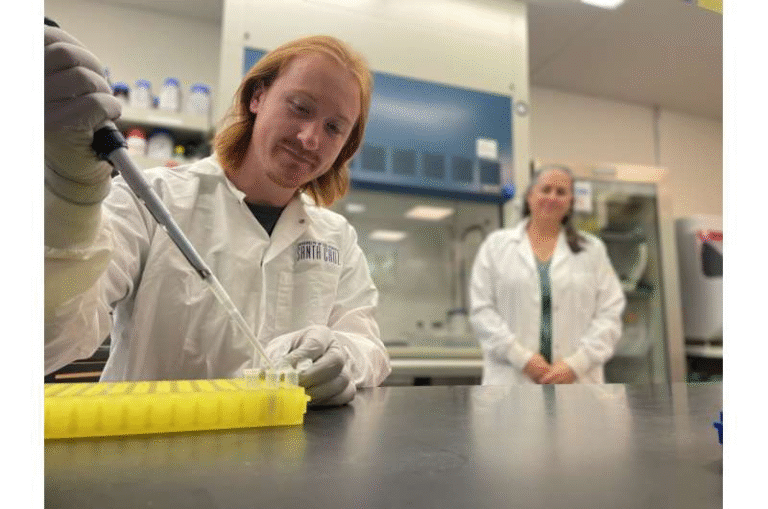

The study was not the work of a single lab. In addition to Ryan Jackson and his students Kadin Crosby and Bamidele Filani at Utah State University, the project involved researchers from several major European institutions.

Collaborators included scientists from:

- The Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research in Germany

- The Helmholtz Center for Infection Research

- Jagiellonian University in Poland

- The University of Strasbourg in France

- The Freie University in Germany

- The Robert Koch Institute

- The University of Veterinary Medicine Austria

- The Institute of Science and Technology Austria

This broad collaboration allowed the team to combine biochemistry, structural biology, and molecular genetics to fully characterize Cas12a3’s function.

Expanding the CRISPR Toolbox

Beyond diagnostics, this discovery highlights the extraordinary diversity of CRISPR systems found in nature. For years, most research focused on a handful of well-known CRISPR proteins. Cas12a3 shows that bacteria have evolved many different strategies to fight viruses, some of which are only now being uncovered.

Understanding these systems at a basic level is crucial. Before CRISPR tools can be safely adapted for clinical or technological use, scientists must know exactly how they function, how they are activated, and what unintended effects they might have.

This research contributes directly to that foundational knowledge.

Looking Ahead

While Cas12a3-based diagnostics are not yet available for clinical use, the discovery provides a strong scientific foundation for future development. With further refinement, this system could lead to faster, safer, and more versatile diagnostic tools, especially for RNA viruses that continue to pose global health challenges.

At the same time, the work reinforces an important lesson in science: basic research matters. By studying how bacteria naturally defend themselves, researchers are uncovering tools that could reshape modern medicine.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09852-9