Decades-Old Clerical Error Led Scientists to Misidentify a Frog That Once Represented an Entire Species

Researchers at the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum recently uncovered an unexpected mistake hiding in plain sight for more than two decades. A simple clerical error caused a poison frog specimen from Peru to be misidentified, leading scientists to believe for years that it represented an entirely separate species. The discovery not only corrected a long-standing taxonomic error but also highlighted why natural history collections and careful record-keeping remain critical to modern science.

At the center of this story is a frog once known as Dendrobates duellmani, a name given in 1999 after a researcher encountered a striking photograph of a colorful frog from the Peruvian rainforest near the Ecuadorian border. Unable to match the frog in the image to any known species at the time, the researcher described it as new to science. To officially name a species, scientists designate a holotype, which is a preserved specimen meant to serve as the definitive reference for that species.

In this case, the holotype was believed to be a specimen housed in the University of Kansas Herpetology Collection, cataloged as KU 221832. That catalog number became permanently associated with the species name. However, as researchers have now discovered, that association was wrong.

The error stemmed from how the species was described in the first place. Instead of examining the physical specimen, the original researcher relied entirely on a photograph. When they requested information from the collection, they asked only for a catalog number, not the specimen itself. Due to a mix-up, they were given the wrong number, which belonged to a different frog entirely. As a result, the new species description became linked to a specimen that did not actually match the frog shown in the photo.

This mistake went unnoticed for years. The name Dendrobates duellmani was cited and reused in subsequent research, quietly embedding the error deeper into scientific literature. It wasn’t until herpetology experts recently visited the Biodiversity Institute to study poison frogs that the problem came to light.

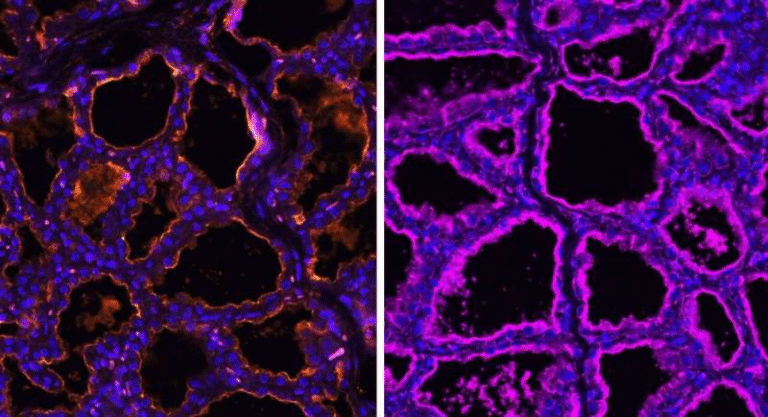

Because the holotype represents the official identity of a species, visiting researchers asked to examine it closely. What they found immediately raised red flags. The frog labeled as the holotype was brown and unremarkable, while the frog in the original photo was brightly colored, a stark and unmistakable difference. That moment triggered a deeper investigation.

Collection manager Ana Motta, who led the effort to untangle the confusion, began retracing decades of records. She and her colleagues carefully examined field notes, photo archives, and specimen data, matching images to preserved frogs one by one. Eventually, they identified the correct specimen that appeared in the original photograph. The frog was real, properly collected, and preserved — it simply had a different catalog number than the one assigned in the species description.

Once the correct specimen was identified, researchers reexamined its classification using modern methods. With access to additional data, including genetic information, it became clear that Dendrobates duellmani was not a distinct species after all. Instead, it belonged to a known species: the Amazon poison frog, scientifically recognized as Ranitomeya ventrimaculata.

This reclassification reflects a broader truth in biology. Sometimes organisms that look very different on the surface turn out to be genetically the same species. In this case, frogs from different populations showed varied color patterns, which initially suggested they might be separate species. However, genetic evidence revealed they were not reproductively isolated and shared significant genetic similarity. What appeared to be multiple species was actually one species displaying a range of natural variation.

The correction was formally published in the scientific journal Zootaxa, where researchers updated both the holotype designation and the type locality of the species. With that, Dendrobates duellmani ceased to exist as a standalone species name and became part of the broader classification of Ranitomeya ventrimaculata.

Beyond fixing a taxonomic mistake, the case raises important questions about how species are described and documented. Traditionally, a holotype was viewed as a single physical object — the preserved animal itself. Today, scientists increasingly think in terms of an extended specimen, which includes not only the physical organism but also all associated data: photographs, genetic sequences, audio recordings of calls, and ecological information.

This broader approach reflects how modern science works, but it also underscores why relying solely on photographs can be risky. Photos capture only limited information and cannot be reanalyzed in the same way a physical specimen can. Without access to the actual frog, the original description could not be independently verified, allowing a simple clerical mistake to persist for decades.

The situation also highlights the growing pressure scientists face to describe species quickly. With habitats disappearing and species going extinct at alarming rates, there is urgency to document biodiversity before it vanishes. While that urgency is understandable, this case serves as a reminder that verifiability and reproducibility are essential to scientific integrity.

Why Natural History Collections Still Matter

Natural history collections may seem like dusty archives, but they are anything but static. They function as living libraries of biodiversity, allowing scientists to revisit old specimens with new tools and new questions. As this case demonstrates, collections can reveal errors, confirm discoveries, and even reshape our understanding of life on Earth.

The University of Kansas herpetology collection, now one of the largest in the world, played a crucial role in resolving this mystery. Without preserved specimens and detailed records, correcting the mistake would have been nearly impossible.

For Motta, the discovery was personally meaningful. Managing collections often involves meticulous, behind-the-scenes work, but moments like this showcase their scientific value. Correcting a long-standing error not only cleans up the scientific record but also improves future research that depends on accurate species identification.

A Closer Look at the Amazon Poison Frog

The Amazon poison frog, now confirmed as the correct identity of the misidentified specimen, is a small but visually striking amphibian native to parts of Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Brazil. Known for its vibrant colors, the frog uses visual signals to warn predators of its toxicity. Interestingly, its poison does not originate within the frog itself but comes from its diet of certain insects in the wild.

Despite its bright appearance, the Amazon poison frog is currently listed as Least Concern in conservation assessments, largely due to its wide distribution. However, habitat loss and climate change remain ongoing threats, making accurate species classification even more important for conservation planning.

A Small Error With Big Lessons

What began as a minor paperwork mistake ultimately affected how scientists understood an entire species for more than twenty years. The resolution of this case reinforces several key lessons: the importance of physical specimens, the dangers of relying solely on images, and the ongoing relevance of natural history collections in a data-driven age.

Science is a self-correcting process, and this frog’s story is a clear example of that principle in action. Even decades later, careful research and attention to detail can bring clarity — and sometimes surprises — to our understanding of the natural world.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5693.1.10