Deep-Sea Mining Could Push Dozens of Shark and Ray Species Toward Extinction

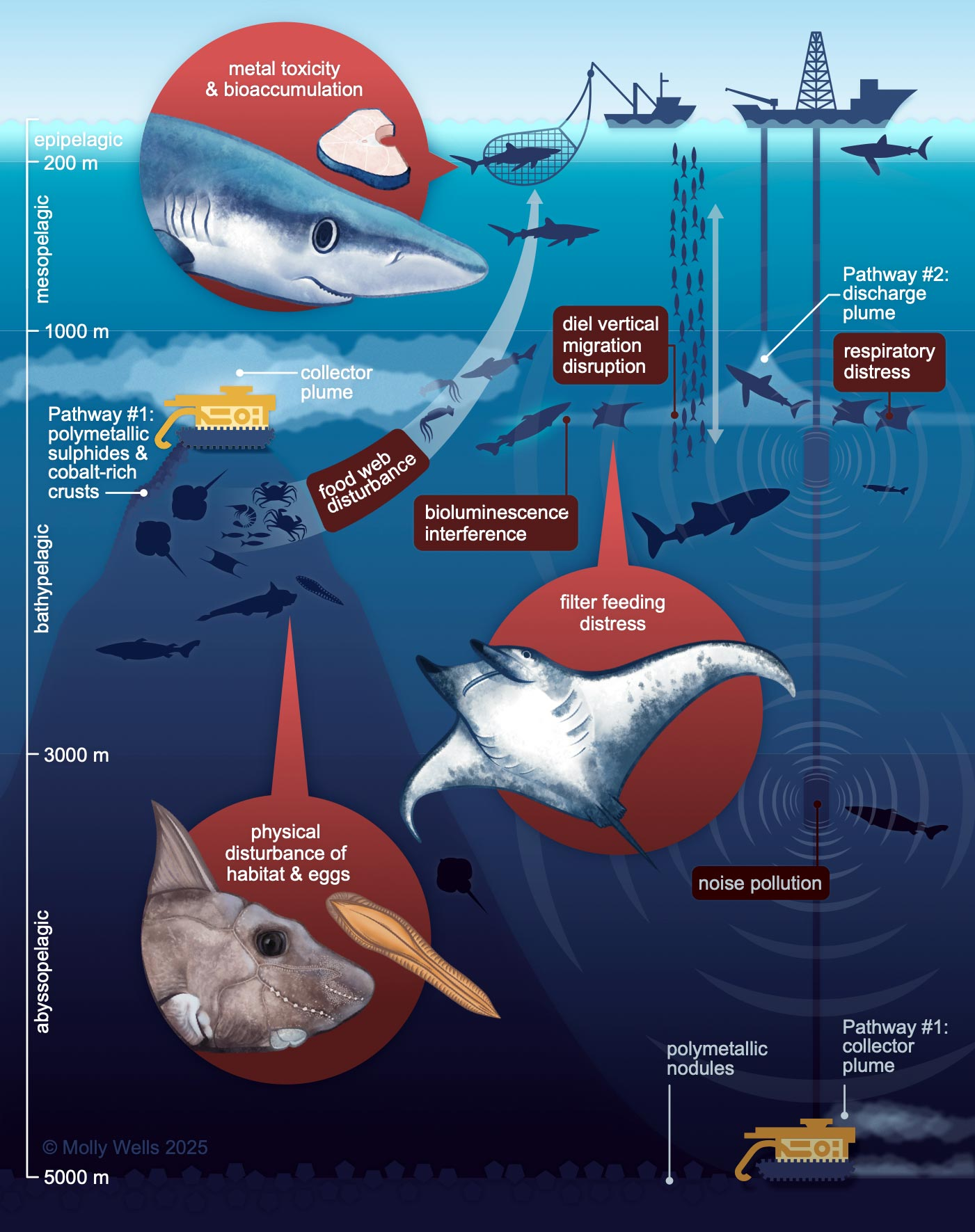

A new scientific study has raised serious concerns about deep-sea mining and its potential to harm sharks, rays, and chimaeras—the ghostly relatives of sharks that inhabit the ocean’s darkest depths. Researchers from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa have discovered that 30 species of these animals live in regions currently being eyed for seafloor mineral extraction, putting them at direct risk of habitat loss and pollution before many are even properly studied.

Published in Current Biology in October 2025, this research paints one of the most detailed pictures so far of how deep-sea mining may threaten already vulnerable marine life. And the findings aren’t comforting: nearly two-thirds of these 30 species are already listed as threatened due to human activities like overfishing, pollution, and habitat destruction. The addition of mining could tip the scales toward extinction for several of them.

What the Study Found

The research team, led by oceanographer Aaron Judah, worked with an international network of experts to map overlaps between shark and ray habitats and proposed mining zones designated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). They compared global range maps from the IUCN Shark Specialist Group with the ISA’s deep-sea mining contracts and reserve areas.

From this mapping, they discovered that:

- 30 species of sharks, rays, and chimaeras live in or near proposed deep-sea mining zones.

- 25 species could face direct habitat disruption from mining machinery scraping the seafloor.

- All 30 species are likely to be exposed to sediment plumes—massive underwater dust clouds stirred up by mining operations.

- For 17 species, these disruptions could affect more than half of their total depth range—an enormous portion of their living space.

These findings suggest that deep-sea mining is not just a small or local problem. It could reshape entire ecosystems across multiple depth layers of the ocean.

Who’s at Risk?

The study covers a mix of both famous and lesser-known species. On one end of the spectrum are charismatic giants like the whale shark, manta ray, and megashark (megamouth)—species that occasionally dive into deeper waters. On the other end are obscure creatures like the pygmy shark (Euprotomicrus bispinatus), which is the world’s second smallest shark, along with the chocolate skate and point-nosed chimaera.

Many of these deep-dwelling species are rarely seen and poorly studied. Some, like skates and chimaeras, lay their eggs directly on the seafloor, meaning that mining vehicles could crush their nurseries or destroy egg cases. Others depend on sediment-sensitive ecosystems, which could be smothered by clouds of silt and metallic dust released by mining activities.

The researchers highlight that these species play vital ecological roles in regulating deep-sea food webs. They are slow-growing, long-lived, and reproduce infrequently—traits that make recovery from disturbances painfully slow.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone: Mining’s New Frontier

One major focus of the study is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), an enormous stretch of seabed between Hawai‘i and Mexico. This abyssal plain, lying between 4,000 and 6,000 meters deep, contains vast fields of polymetallic nodules—small, metal-rich rocks containing nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese.

These minerals are highly sought after for use in batteries, electric vehicles, and renewable energy technologies, fueling a global push toward mining the deep sea. But the CCZ is also home to an extraordinary variety of deep-sea organisms, many of which have never been formally named or described.

The study warns that disturbance in the CCZ could have far-reaching effects, especially because many deep-sea species are highly mobile. Some sharks and rays travel across enormous oceanic distances, meaning that damage in mining zones could indirectly affect ecosystems near places like Hawai‘i or other Pacific island chains.

How Deep-Sea Mining Harms Marine Life

Mining the seafloor involves sending heavy robotic machines to the ocean bottom to vacuum up mineral-rich sediments. These machines churn up fine particles that drift through the water column, forming sediment plumes that can stretch for hundreds of kilometers.

The study identifies several main pathways of harm:

- Physical Habitat Destruction

Mining vehicles can crush or scrape the seabed, destroying fragile habitats such as sponge fields, corals, and nursery grounds where sharks and rays lay eggs. - Sediment Pollution

The fine sediment released can clog gills, block light, and smother eggs and larvae. These plumes may also carry toxic heavy metals, further contaminating the ecosystem. - Disruption of Midwater Zones

Plumes don’t just stay on the seafloor. They drift upward, affecting midwater species that rely on clear water for hunting or navigation. - Fragmentation of Habitats

Continuous mining operations can create isolated “islands” of suitable habitat, reducing genetic exchange between populations. - Indirect Ecosystem Impacts

Changes to food availability, prey abundance, and chemical composition of water can ripple upward through the food chain, affecting larger predators like sharks and rays.

Because the deep sea is so stable and slow-changing, disturbances may take centuries or even millennia to recover from—if recovery is possible at all.

Conservation Recommendations

The authors of the study aren’t just sounding the alarm—they’ve outlined several practical steps that could be taken to protect these animals if deep-sea mining proceeds:

- Include sharks, rays, and chimaeras explicitly in environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for mining projects.

- Establish baseline monitoring programs to understand existing populations before mining begins.

- Create protected zones within or near mining regions to safeguard critical habitats.

- Limit sediment discharge and control plume spread through engineering solutions.

- Require regular reassessments of environmental risks as more data become available.

They emphasize that a precautionary approach is essential, given how little is currently known about deep-sea ecosystems. Once damage occurs, there may be no way to undo it.

The Bigger Picture: Why Deep-Sea Mining Matters

While the study zeroes in on sharks and rays, the issue of deep-sea mining is far broader. The practice is being driven by the growing demand for transition metals needed in clean energy technologies—a classic example of one environmental challenge (climate change) potentially fueling another.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN-affiliated body, oversees mining in international waters. As of 2025, the ISA has issued over 30 exploration licenses to companies and governments seeking to extract minerals from the seafloor. However, commercial-scale mining has not yet begun, largely because of unresolved environmental concerns.

Critics argue that regulations are rushing ahead of science, with the ISA under pressure from companies to finalize mining rules. Conservationists and many scientists have called for a moratorium—a temporary pause—on deep-sea mining until we better understand its consequences.

Why the Deep Sea Is So Fragile

The deep ocean is a world of extremes: cold, dark, and slow-moving. Food is scarce, and most organisms have adapted to stable conditions. When disturbed, these ecosystems don’t bounce back quickly.

Deep-sea animals often have:

- Slow growth rates

- Long lifespans (some deep-sea sharks live for centuries)

- Low reproductive rates

These traits make them particularly vulnerable to any kind of disturbance. When mining scrapes away layers of sediment, it may destroy communities that have been developing undisturbed for millions of years.

Scientists studying deep-sea ecosystems have found that tracks left by experimental mining machines decades ago are still visible today, with minimal recovery of the affected seabed. That’s a stark warning about what industrial-scale mining could do on a much larger scale.

Why Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras Matter

These animals aren’t just fascinating oddities of the deep—they’re essential to ocean health. Sharks and rays are top or mid-level predators, keeping prey populations in check and maintaining balance in marine ecosystems. Chimaeras, often called “ghost sharks,” are deep-sea specialists that help cycle nutrients between the seabed and the water column.

Their disappearance would create a cascade of ecological changes, affecting everything from microbial life to commercial fisheries. It’s also a cultural loss: many island nations and coastal communities have deep connections to sharks, seeing them as symbols of strength or guardians of the sea.

A Call for Precaution

The researchers stress that we’re on the brink of industrializing one of Earth’s last untouched frontiers. Deep-sea mining could unlock valuable metals, but it could also wipe out species before we even know they exist.

The study’s message is clear: without strong environmental safeguards, deep-sea mining might erase life forms we’ve only just discovered. As our understanding of the deep ocean grows, so does our responsibility to protect it.

For now, scientists urge international regulators and mining companies to slow down, invest in more research, and treat the deep sea as a shared global heritage, not just a source of resources.

Research Reference:

“Deep-sea mining risks for sharks, rays, and chimaeras” – Current Biology, October 2025