Discovery of a New Genetic Code in Archaea Is Opening Major Opportunities for Bioengineering

Scientists have uncovered something remarkable hiding in plain sight within a wide range of microbes called archaea: a completely new genetic code that changes how these organisms read their own DNA. This discovery not only reshapes how we think about genetic evolution but also opens up valuable possibilities for biotechnology, greenhouse-gas research, and the production of novel proteins.

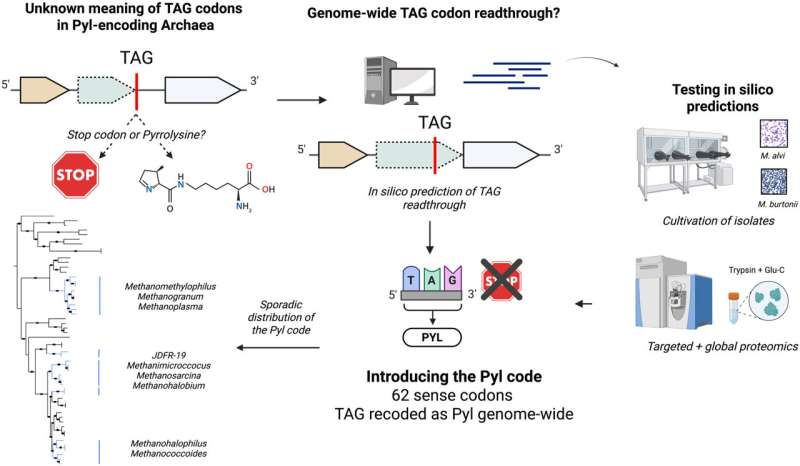

At the center of this finding is a fundamental shift in how certain archaea interpret one of the three standard stop codons in DNA, specifically the TAG codon. In most forms of life, TAG functions as a hard stop during protein synthesis. But in these newly studied archaea, TAG no longer means “stop.” Instead, it consistently codes for the uncommon amino acid pyrrolysine. This may sound like a small change, but genetically speaking, it is huge—because it means these microbes operate with an expanded genetic code where all TAG codons are treated as instructions to add an amino acid, not end a protein.

The research team—led by Veronika Kivenson and IGI Investigator Jill Banfield, along with collaborators at UC Berkeley, CGEM, Institut Pasteur, and others—reported their findings in a recent Science (2025) publication. Their analysis revealed that this alternative genetic system appears in multiple archaeal lineages, not just a few rare species as previously believed. This means nature has independently evolved this code several times, challenging the long-held idea that genetic codes are nearly impossible to change once established. Instead, genetic code flexibility may be more common than scientists ever expected.

A standard genetic code uses 64 codons: 61 for amino acids and 3 for stop signals. Expanded genetic codes have been observed before, but usually in scattered, rare proteins. What sets this discovery apart is its genome-wide consistency. In these archaea, all TAG codons—without exception—code for pyrrolysine. Prior to this insight, researchers studying these microbes misinterpreted the TAG codons as stops, which caused them to overlook hundreds of full-length proteins containing pyrrolysine. These proteins simply appeared truncated or nonsensical because the codon was being incorrectly interpreted during gene analysis. With the corrected genetic interpretation, scientists can finally see the true structure and function of these proteins.

A major reason this unusual genetic code matters is because many of these archaea participate in methane cycling. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas—27 times stronger than carbon dioxide in terms of warming impact. The archaea using this code are typically methanogens, organisms that produce methane as part of their metabolic process. Much of this activity involves breaking down methylamines, a group of environmental compounds whose methyl groups are eventually converted into methane.

The enzymes responsible for these reactions require pyrrolysine at key positions, which explains why these microbes evolved a genetic system that ensures pyrrolysine gets inserted reliably. Without the reassignment of TAG, they wouldn’t be able to produce the full suite of enzymes needed to thrive in their environments. In other words, the switch from stop codon to pyrrolysine codon appears to have been driven by metabolic necessity, not random mutation.

Understanding this code correctly now gives scientists better tools for studying how these methanogens influence global methane emissions. By identifying the full set of pyrrolysine-containing proteins, researchers can more accurately map the biochemical networks that produce methane in natural environments. This could eventually help guide strategies to reduce methane emissions, an important climate-related goal.

Beyond environmental science, this discovery has major implications for bioengineering and synthetic biology. For nearly 25 years, scientists have been intentionally expanding genetic codes in laboratory organisms to create proteins with unnatural amino acids. The idea was first demonstrated by Peter Schultz at UC Berkeley, who engineered microbes to reinterpret a stop codon so that it inserts a non-natural amino acid instead. These expanded codes have since been used to produce custom-designed proteins for medicines, antibody technologies, and industrial applications.

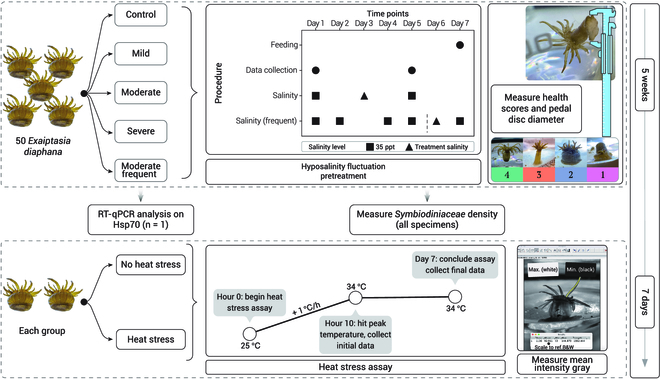

The newly identified archaeal systems may serve as high-efficiency natural templates for improving this kind of genetic engineering. Recognizing this potential, Banfield’s team partnered with UC Berkeley chemist and synthetic biologist Alanna Schepartz. Schepartz’s group tested pyrrolysine translation components from eight different archaeal groups by introducing them into E. coli bacteria. The experiment was simple: the bacteria were engineered to include a fluorescent protein gene containing a TAG codon in the middle of the sequence. Normally, this would result in a truncated, non-glowing protein. But when supplied with the archaeal pyrrolysine machinery, E. coli successfully interpreted the TAG codon as pyrrolysine and produced a complete, glowing fluorescent protein.

All eight archaeal systems worked exactly as predicted. This verification suggests that these natural pyrrolysine-reading systems could become valuable tools for producing custom proteins with greater reliability and fewer engineering hurdles. One challenge with current genetic code expansion technology is its unpredictability—success often depends on the surrounding RNA sequence, the organism used, and the structure of the new amino acid. The archaeal systems appear to have evolved more consistently functioning solutions, offering insights that biotech researchers can build upon.

To deepen understanding of this topic, it helps to step back and look at pyrrolysine itself. Often called the “22nd amino acid,” pyrrolysine is structurally more complex than standard amino acids. It occurs naturally in only a few groups of organisms and requires a specialized set of enzymes and tRNAs for incorporation into proteins. Unlike most organisms, which rarely or inconsistently use pyrrolysine, the archaea identified in this study rely on it heavily, which explains why their genomes have hard-wired a codon reassignment to guarantee its placement.

It’s also useful to appreciate why genetic codes are generally so stable. The genetic code is shared across all known life, and changing it usually causes catastrophic misreading of existing genes. Yet these archaea show that if the evolutionary pressure is strong enough—and if the organism can adjust its genome accordingly—complete codon reassignment can happen. This adds to a growing body of evidence that genetic codes are not entirely “frozen” but can evolve in special circumstances.

Overall, the discovery of a fully reassigned codon across multiple archaeal groups gives scientists a powerful new lens for studying evolution, global carbon cycles, and protein engineering. It corrects long-standing misinterpretations in genomic data, explains the metabolic strategies of key methane-producing microbes, and provides promising new biological tools for synthetic chemistry and biotechnology.

Research Paper:

An archaeal genetic code with all TAG codons as pyrrolysine (Science, 2025)