DNA Packaging Once Seen as an Obstacle Is Now Helping Genes Get Expressed

For decades, biology textbooks have described nucleosomes—the structures that tightly package DNA—as obstacles that slow down or block gene expression. New research from Cornell University, however, shows that this long-held view is incomplete. Instead of merely getting in the way, nucleosomes can actually help gene expression move forward by reducing mechanical stress in DNA during transcription.

This discovery comes from a study published in Science in 2025, led by Michelle Wang, the James Gilbert White Distinguished Professor of the Physical Sciences at Cornell, with Jin Qian, a postdoctoral researcher, as the lead author. The work provides fresh insight into one of the most fundamental processes in biology and explains how cells manage to keep gene expression running smoothly despite intense physical strain at the molecular level.

Why Gene Expression Is So Mechanically Challenging

Gene expression begins with transcription, the process in which RNA polymerase II copies genetic information from DNA into RNA. This step is essential for virtually every cellular function. If transcription goes wrong, the consequences can be severe, ranging from abnormal cell growth to cancer and other diseases.

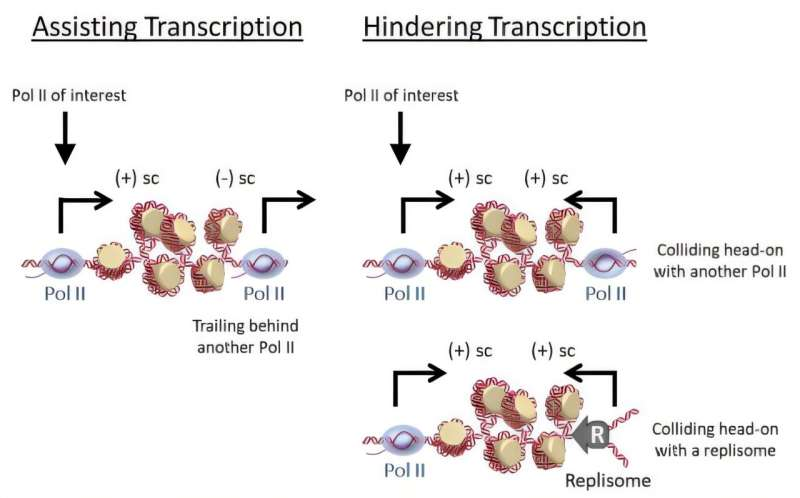

The challenge lies in DNA’s physical structure. DNA is a right-handed double helix, meaning its strands are twisted together like a spiral staircase. When RNA polymerase moves along DNA, it must both travel forward and rotate to follow this helical path. That movement introduces torsional stress, similar to what happens when you try to untwist one part of a tightly coiled rope—the rest of the rope tightens.

As transcription progresses, DNA ahead of the polymerase becomes overwound, while DNA behind it becomes underwound. This buildup of torque can slow or even stall transcription if the stress is not properly managed.

The Traditional View of Nucleosomes

Adding to the difficulty is the presence of nucleosomes. DNA in cells is not free-floating; it is wrapped around protein complexes called histones, forming nucleosomes that together make up chromatin. Each nucleosome wraps DNA tightly, and for years, scientists believed these structures mainly acted as physical barriers that RNA polymerase had to overcome.

From this perspective, transcription was seen as a constant battle—polymerase pushing through tightly packed chromatin while simultaneously dealing with torsional stress caused by DNA twisting. The new research shows that this view misses an important mechanical advantage hidden within chromatin itself.

A Crucial Detail: Opposing Twists

The Cornell team discovered that nucleosomes have a built-in property that helps counteract torsional stress. While DNA naturally twists to the right, nucleosomes wrap DNA in a left-handed direction. This opposing chirality turns out to be critically important.

As RNA polymerase moves forward and generates torsional stress, nucleosomes can partially absorb and redistribute that stress. In effect, chromatin acts as a torsional buffer, reducing the mechanical resistance faced by the polymerase. Rather than simply blocking transcription, nucleosomes help stabilize the system and allow gene expression to continue.

This finding helps explain how transcription can proceed efficiently even in regions of DNA that are densely packed with nucleosomes.

How Scientists Measured DNA Torque

Understanding these mechanics required more than traditional biochemical tools. Wang’s lab has spent decades developing advanced instruments capable of probing DNA at the single-molecule level.

One of their key innovations is the angular optical trap, which uses a nanofabricated quartz cylinder to grip one end of a DNA molecule and precisely measure twisting forces. They also developed magnetic tweezers, which use magnetic fields to stretch and twist DNA strands.

By combining these tools, the researchers could directly measure torque, rotation, and angular orientation in DNA during transcription. This experimental setup allowed them to see how nucleosomes influence torsional stress in real time, something that was not possible before.

The Role of Topoisomerases

The study also highlights the importance of topoisomerases, enzymes that act like molecular scissors. These proteins temporarily cut DNA strands, allowing them to unwind and release accumulated torsion before sealing the breaks again.

While topoisomerases help manage extreme levels of stress, the new findings show that nucleosomes themselves provide a continuous buffering effect. Together, nucleosomes and topoisomerases form a coordinated system that keeps transcription moving forward under mechanical strain.

With sufficient topoisomerase activity, RNA polymerase can pass through multiple nucleosomes without stalling, even as torsional stress builds up along the DNA.

Why This Changes How We Think About Chromatin

This research shifts chromatin from being seen as a passive obstacle to being recognized as an active mechanical participant in gene regulation. The physical properties of nucleosomes—specifically their left-handed wrapping—play a direct role in maintaining transcription efficiency.

According to Wang, this discovery fills in an important missing piece of the puzzle. Gene expression sits at the heart of biology’s central dogma, and understanding how it is regulated mechanically helps explain how cells maintain stability while responding to changing conditions.

Broader Implications for Biology and Medicine

The findings open the door to many new questions. Nucleosomes are not static structures; they can be chemically modified, repositioned, or removed entirely. These changes may alter chromatin’s mechanical properties, potentially influencing how easily RNA polymerase moves through a gene.

This has implications for understanding diseases linked to gene regulation, including cancer. Abnormal chromatin structure or disrupted torsional buffering could interfere with transcription, leading to widespread cellular dysfunction.

The work also reinforces the idea that biology is deeply influenced by physics. Complex biological behaviors can emerge from relatively simple physical principles, such as torque, rotation, and mechanical resistance.

A New Direction for Gene Expression Research

Michelle Wang, who was reappointed as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator in 2025, sees this research as just the beginning. Future studies may explore how different chromatin states affect transcription mechanics, how nucleosome remodeling complexes influence torsional buffering, and how these processes interact during DNA replication as well as transcription.

By revealing that DNA packaging can be both a challenge and a solution, this study reshapes our understanding of how genetic information is decoded inside living cells.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adv0134