Early Embbryo Development Isn’t Symmetrical After All and Science Now Knows Why

For a long time, scientists believed that the very earliest stages of mammalian life were simple and uniform. According to this traditional view, when a fertilized egg divides into two cells, those two cells are essentially identical, each carrying the same potential and destiny. A new study published in the journal Cell turns that idea on its head. Researchers have now shown that embryos display specialized asymmetry at the two-cell stage, much earlier than anyone expected.

This discovery doesn’t just reshape how developmental biology understands the beginning of life. It also carries meaningful implications for fertility research, in-vitro fertilization (IVF), and embryo viability, areas that affect millions of people worldwide.

Why Early Embryo Biology Matters

Roughly one in six couples experience fertility challenges, and IVF has become a widely used reproductive technology. Despite decades of use, IVF success rates remain limited, partly because scientists still do not fully understand what makes one embryo viable and another fail to develop.

Early embryonic development is a critical piece of that puzzle. If researchers can identify the earliest signs that predict healthy development, it could eventually improve embryo selection and treatment strategies. That is why this new study, which looks at embryos at their very first cell division, has attracted so much attention.

A Closer Look at the Two-Cell Embryo

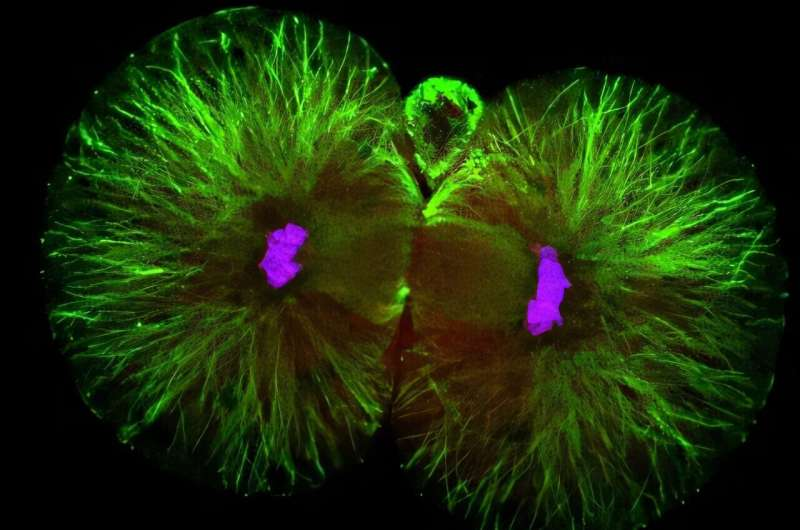

The study was conducted primarily in the laboratory of Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, Bren Professor of Biology and Biological Engineering at Caltech. The research focused on mouse embryos immediately after fertilization, specifically at the moment when a single fertilized egg divides into two cells, known as blastomeres.

Previously, scientists assumed that these two blastomeres were equivalent. The new findings show that this assumption was incorrect. Using advanced proteomic analysis, the researchers found that the two cells are biologically different almost from the start.

In fact, the team identified around 300 proteins that are unevenly distributed between the two blastomeres. Some proteins are produced in higher amounts in one cell, while being scarce in the other. These proteins are not random or trivial. Many of them play key roles in building new proteins, breaking down old ones, and managing the transition from maternal instructions to embryonic control.

One Cell Builds the Body, the Other Supports It

One of the most striking discoveries is that these early differences appear to influence the future roles of the cells. The researchers found that the blastomere that retains the site of sperm entry after division tends to contribute most of the cells that form the developing body. The other blastomere primarily contributes to the placenta, which supports the embryo during pregnancy.

This challenges the long-held belief that cell fate decisions in mammals happen much later, after many rounds of division. Instead, the study suggests that the blueprint for body versus placenta may begin forming at the very first split.

The Surprising Role of Sperm Entry

Developmental biologists have traditionally viewed sperm as a delivery system for genetic material. This research suggests the story is more complex. The location where the sperm enters the egg appears to act as a spatial signal that helps establish asymmetry during the first division.

Exactly how this happens remains unclear. The sperm might be introducing specific cellular structures, delivering regulatory RNA molecules, or even creating a mechanical cue that influences how the embryo organizes itself. Understanding this mechanism is now a major focus for future research.

Human Embryos Show the Same Pattern

Although the main experiments were performed in mice, the researchers also examined human embryos at the same early stage. Remarkably, they found that human two-cell embryos also show strong molecular differences between their blastomeres.

This suggests that early asymmetry is not a quirk of mouse biology but a conserved feature across mammals. That makes the findings especially relevant for human reproductive medicine and developmental science.

Rethinking Early Totipotency

For decades, biology textbooks taught that early embryonic cells are totipotent, meaning each cell has the same ability to develop into any part of the organism. While totipotency still holds in a broad sense, this study shows that totipotent cells can still be molecularly different.

In other words, early cells may have equal potential but are already biased toward specific developmental paths. This nuance helps reconcile earlier observations that splitting embryos at early stages can still produce healthy organisms, even though the cells are not truly identical at the molecular level.

Protein Regulation at a Critical Transition

Another key insight from the study involves the timing of protein control. Early embryos rely heavily on proteins and instructions supplied by the mother. As development progresses, the embryo must take over this process itself. The proteins found to be asymmetrically distributed are heavily involved in managing this handover of control.

This suggests that early asymmetry may help coordinate how and when different parts of the embryo assume responsibility for growth and organization, adding another layer of precision to early development.

What This Means for IVF and Fertility Research

While the study does not immediately change clinical practice, it provides an important direction for future fertility research. If scientists can learn to detect or interpret early asymmetry, it could eventually help identify embryos with a higher chance of successful development.

However, the researchers emphasize that much more work is needed before these insights can be translated into medical tools. Understanding cause versus correlation, and determining how environmental factors influence early asymmetry, remain open questions.

Extra Context: How Embryo Research Has Evolved

Embryology has progressed rapidly over the last few decades thanks to advances in imaging, molecular biology, and single-cell analysis. Techniques that allow scientists to study individual cells and their protein composition were simply not available when earlier assumptions about symmetry were formed.

This study is a good example of how new tools can reveal hidden complexity in processes once thought to be straightforward. Early development, it turns out, is not just a matter of repeated division, but a carefully coordinated sequence of molecular decisions happening from the very beginning.

Looking Ahead

The discovery of early embryonic asymmetry raises new questions as much as it answers old ones. How universal is this process across species? Can environmental conditions influence early asymmetry? And most importantly, can this knowledge be safely and ethically applied to improve reproductive health?

For now, the study offers a powerful reminder that life’s earliest moments are far more structured and purposeful than they appear under a microscope.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.006