Engineered Poplar Trees Show Promise for Producing Biodegradable Plastic Ingredients and Stress-Resistant Biomass

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory have successfully reprogrammed poplar trees to act as living production units for several valuable industrial chemicals, including a key ingredient used in making biodegradable plastics. This new research demonstrates how genetically engineered trees could contribute to a flexible and sustainable biomanufacturing system while also offering advantages for biofuel production and growth on poor-quality soils.

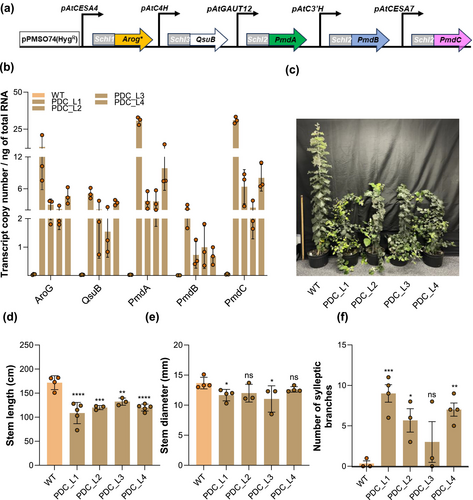

The work, published in Plant Biotechnology Journal, focuses on hybrid poplar trees that were modified to generate high levels of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC). This compound is normally produced through complex chemical synthesis or microbial fermentation, and it serves as a building block for durable, biodegradable plastics and high-performance coatings. In this study, researchers inserted five genes from soil microbes into the poplar genome. These genes form a synthetic metabolic pathway that redirects part of the tree’s natural metabolic flow toward producing PDC and other related chemicals.

Alongside PDC, the engineered poplar trees also produced notable quantities of protocatechuic acid (PCA) and vanillic acid (VA)—two compounds with various industrial and pharmaceutical applications. This confirms the metabolic flexibility of poplar and shows how modifying plant pathways can yield several valuable compounds simultaneously.

One of the key advantages of poplar as a biological production system is its adaptable nature. These trees grow rapidly, root easily, and tolerate diverse environments. With this new synthetic pathway introduced, they can now generate additional bioproducts without compromising their growth. In fact, the genetic modifications triggered several other beneficial changes that further increase their usefulness.

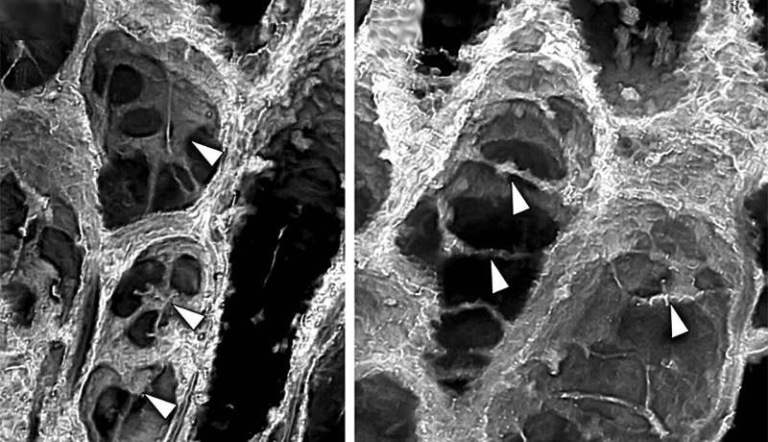

A major shift occurred in the composition of the poplar cell walls. The engineered trees had reduced lignin, a tough structural polymer that makes biomass difficult to break down during processing. Lower lignin levels make the plant material much easier to convert into biofuels or other chemical feedstocks. At the same time, the modified plants showed higher hemicellulose content, which includes more readily extractable complex sugars.

These biochemical changes had significant effects during saccharification—the process of breaking biomass down into fermentable sugars. Compared to unmodified poplars, the engineered trees yielded up to 25% more glucose and 2.5 times more xylose, both of which are essential components for biofuel production and additional bioproduct pathways. This means the same engineered tree can serve dual roles: supplying biodegradable plastic precursors and simultaneously providing more efficient biomass for biofuel production.

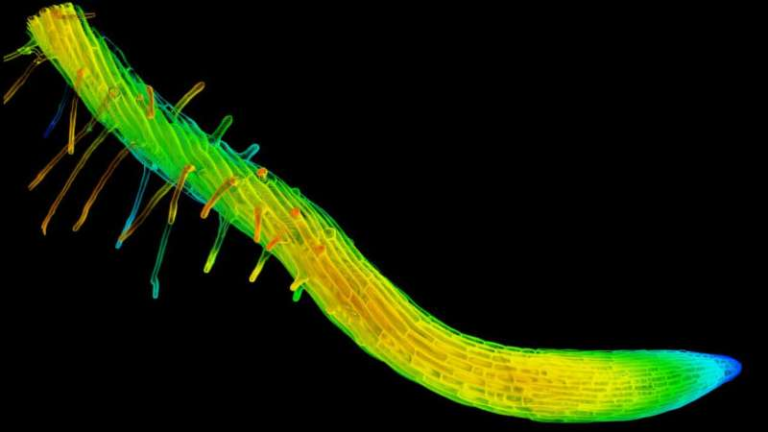

Another notable change involved the buildup of suberin, a waxy protective material, in the bark and roots. Suberin strengthens plant tissues, improves water retention, and helps block toxins. Because of this increase, the modified poplars demonstrated enhanced tolerance to high soil salinity, allowing them to grow better in poor or marginal soils that are not suitable for food crops.

This has significant implications for land use. Since these engineered poplars can thrive in non-arable, salt-affected soil, they do not compete with food production and could be cultivated on land that typically goes unused. Even more interestingly, when the trees were exposed to salt stress, they produced higher levels of bioproducts like PDC than they did under ideal conditions. This could open up productive uses for degraded or marginal lands.

So far, all the experimental results come from greenhouse conditions. The next step for the research team is to evaluate how the engineered poplars perform outdoors in long-term field trials. These tests will determine how stable the introduced metabolic pathway remains over multiple growth cycles and whether the enhanced chemical production and stress tolerance hold up under real environmental pressures.

The broader potential of this research lies in the scalability and flexibility of using plants as biofactories. Unlike traditional chemical plants or fermentation facilities, engineered trees grow using sunlight, carbon dioxide, and soil nutrients. They do not require expensive manufacturing infrastructure and can be modified further if demand shifts. The study demonstrates that by depending on specific combinations of genes, researchers can direct plant metabolism to produce many different valuable compounds—not just PDC, PCA, or VA.

This represents a shift toward plant-based manufacturing, where living systems supply raw materials tailored to industrial needs. Developing such systems could reduce dependence on imported specialty chemicals, strengthen domestic supply chains, and lower environmental impact. With ongoing optimization, these engineered poplar trees could support U.S. industries ranging from bioplastics and biofuels to pharmaceuticals and green chemical production.

To better understand how impactful this development could be, it helps to know more about PDC itself. Although it’s not a widely recognized compound outside scientific circles, PDC is an important biobased monomer that can be polymerized into strong, transparent, and fully biodegradable plastics. These plastics can serve as alternatives to petroleum-derived materials used in packaging, coatings, adhesives, and specialty polymers. Producing PDC at scale has historically been a challenge because conventional routes are complex and costly. Embedding PDC production directly into biomass sidesteps many of these issues.

It’s also worth looking at why poplar is frequently chosen in bioenergy and bioengineering research. Poplar trees grow quickly, reaching harvestable size in just a few years. They have a well-studied genome, making them easier to genetically modify than many other tree species. They are also perennials, which means that once planted, they continue to grow season after season without needing to be reseeded. Their fast growth and high biomass output make them ideal candidates for renewable material production.

Poplar also has strong ecological flexibility. Different varieties tolerate a wide range of temperatures, moisture conditions, and soil types. Many hybrid poplars are already used in environmental applications such as soil reclamation, wastewater management, and carbon sequestration. The ability to engineer them further widens their usefulness.

In the context of bioeconomy development, engineered plants like these poplars offer an appealing route toward decentralized production. Instead of relying solely on centralized factories, a region could grow and harvest chemical-producing biomass depending on local demand. By optimizing the introduced metabolic pathways, scientists could adjust the chemical profiles of the trees—potentially producing adhesives, solvents, polymers, antioxidants, or even pharmaceuticals directly in plant tissues.

This newly published research does more than demonstrate one successful case of pathway engineering; it shows that plant metabolism is highly adaptable. By harnessing this adaptability, scientists can design crops that not only survive environmental stress but also generate useful materials under those conditions. As global industries increasingly look for sustainable alternatives to petrochemicals, plant-based production systems like engineered poplar could become an important part of the solution.

Field trials will be crucial for determining how feasible this approach is for commercial use. Factors such as growth rate, long-term genetic stability, environmental interaction, harvesting logistics, extraction efficiency, and economic viability all need to be assessed. But the foundation laid by this study is promising. It demonstrates that with the right combination of microbial genes and plant engineering strategies, trees can be turned into multi-purpose biological factories capable of producing high-value chemicals at scale.

For anyone following developments in green chemistry, bioengineering, or renewable materials, this work marks an exciting step toward a more sustainable and flexible manufacturing future.

Research Paper:

Engineering 2-Pyrone-4,6-Dicarboxylic Acid Production Reveals Metabolic Plasticity of Poplar

https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.70414