Fiji’s Ants Are Disappearing: A Deep Dive into the Insect Apocalypse

Scientists have uncovered alarming evidence that 79% of Fiji’s native ant species are in decline, providing some of the clearest genomic proof yet of what researchers call the “Insect Apocalypse.”

Published in Science in September 2025, the study sheds light on how fragile island ecosystems can unravel when faced with human impact, invasive species, and changing environments.

This research, led by an international team from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), the University of Maryland, and the Australian National University, uses a groundbreaking approach called museumomics—sequencing DNA from museum specimens collected over decades.

By analyzing thousands of ant genomes, scientists pieced together the evolutionary history of Fiji’s ants, their colonization patterns, and how their populations have changed over time. The findings are stark: endemic species are shrinking, while non-native and invasive species introduced by humans are booming.

The Scope of the Study

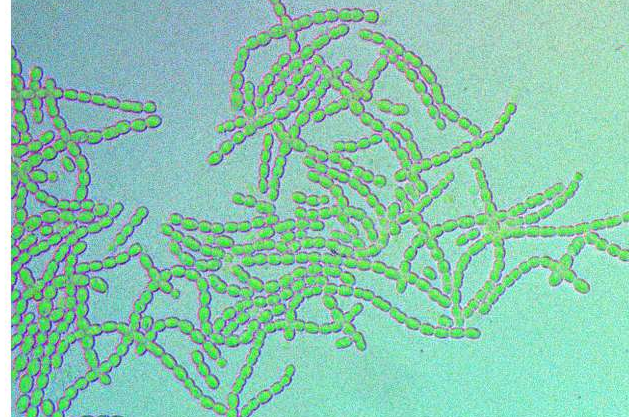

The research team sequenced genomes from over 4,000 ant specimens, covering more than 100 confirmed species in the Fijian archipelago. These ants were collected through decades of fieldwork, both recent and historical, and stored in museum collections around the world.

By applying population genetics models to this genomic data, scientists identified 65 separate colonization events—moments when different ant species first arrived in Fiji. These ranged from ancient natural arrivals millions of years ago, to recent human-mediated introductions linked to global trade.

But the most striking finding was the 79% decline among Fiji’s endemic ants. These species exist nowhere else in the world and are highly adapted to the island’s ecosystems. In contrast, introduced ants, brought accidentally through trade or agriculture, are thriving and spreading, particularly in lowland and disturbed areas.

When Did the Declines Start?

The genomic evidence shows that the downturn in ant populations is not just recent. It began thousands of years ago with the arrival of humans in Fiji around 3,000 years ago. However, the decline accelerated sharply in the last several centuries, coinciding with European contact, colonization, global trade, and the spread of modern agriculture.

This aligns with broader patterns of biodiversity loss across island ecosystems worldwide. Once humans arrive, ecosystems face multiple stressors: land-use change, deforestation, the introduction of invasive species, and later industrial-scale disruptions.

Endemic vs. Non-Native Species

Not all ants have been affected equally. Endemic species—those with narrow habitat preferences and unique evolutionary histories—are the hardest hit. Many of them are confined to high-elevation forests or highly specific ecological niches. These ants evolved in isolation and lack the resilience to cope with invasive competitors or large-scale habitat changes.

Meanwhile, non-native ants introduced through human activity are expanding rapidly. Widespread Pacific ants and invasive global species thrive in lowland disturbed habitats, agricultural areas, and urban environments. These species often outcompete natives, contributing further to their decline.

Even some regional Pacific species, not strictly endemic to Fiji, are holding steady or expanding. This points to a pattern where generalist, adaptable ants benefit from disturbance, while specialist endemic ants decline.

The Importance of Museumomics

One of the challenges in studying insect populations is the lack of long-term monitoring data. Unlike large mammals or birds, insects have rarely been tracked systematically over centuries. That’s where museumomics comes in.

DNA degrades over time, but with new sequencing techniques, scientists can extract genetic fragments even from old, preserved specimens. By comparing these fragments across thousands of individuals, researchers can estimate whether populations have been expanding or shrinking.

In this study, museum collections became essential archives for reconstructing Fiji’s ant biodiversity. Without these resources, scientists would have no way to measure such long-term trends.

Why Islands Matter

Islands like Fiji are often referred to as “canaries in the coal mine” for biodiversity. Their ecosystems are closed and isolated, meaning they feel the effects of change faster than large continental systems. They also have high rates of endemism—species found nowhere else—which makes them especially vulnerable to extinction.

Historically, most documented extinctions of birds, reptiles, and insects have occurred on islands. Small ranges, specialized adaptations, and the inability to escape disturbances all contribute to this heightened risk.

Broader Implications: The “Insect Apocalypse”

The Fiji study is part of a larger global discussion on insect decline. Insects play vital roles:

- Pollination: They fertilize many flowering plants, including crops humans rely on.

- Decomposition: Insects break down dead organic matter, recycling nutrients into ecosystems.

- Food webs: Birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals depend on insects as a primary food source.

Global reports already suggest that many insect populations are collapsing, especially in Europe and North America. However, long-term data from tropical regions have been sparse. This study provides one of the strongest pieces of evidence yet that the Insect Apocalypse is not confined to temperate zones—it is global.

What’s Driving the Decline?

The Fiji study doesn’t pinpoint a single cause but highlights overlapping pressures:

- Habitat destruction: Clearing forests for agriculture or development reduces available habitat.

- Invasive species: Non-native ants outcompete and sometimes prey on native ants.

- Agricultural change: Modern farming practices alter soil and vegetation, disrupting habitats.

- Climate change: Rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns affect tropical ecosystems.

- Global trade: Ships, planes, and commerce increase the rate of invasive species introductions.

Taken together, these factors create what scientists call “multiple stressor scenarios”, where each impact compounds the others.

Beyond Fiji: Can We Generalize?

While the study focuses on Fiji, it raises important questions for other island ecosystems. Are other Pacific islands showing similar patterns? What about tropical islands in the Caribbean or Indian Ocean?

It’s also a cautionary tale for continental systems. Even though larger landmasses are less isolated, insect declines are already well-documented in Europe, where agricultural intensification has been linked to biodiversity loss.

The Value of Biodiversity Collections

One of the biggest takeaways from this study is the value of biodiversity museums and collections. These archives allow scientists to study changes that would otherwise be invisible.

Modern technology makes it possible to extract more information than ever before. Genomes can reveal population trends, colonization histories, and evolutionary relationships, all from specimens that may have been sitting in drawers for decades.

This underscores the need to continue investing in natural history collections and maintaining them as critical global resources.

Adding Context: Other Cases of Insect Decline

The Fiji ant story fits into a bigger picture of insect decline worldwide. For instance:

- In Germany, long-term surveys in nature reserves showed a 75% decline in flying insect biomass over just 27 years.

- In North America, monarch butterfly populations have dropped dramatically due to habitat loss and pesticide use.

- In the tropics, deforestation in the Amazon and Southeast Asia has led to sharp reductions in insect diversity.

Each of these cases highlights the same pattern: insects are extremely sensitive to human-driven change, and once they decline, entire ecosystems feel the effects.

What Can Be Done?

Conservationists argue that tackling insect decline requires:

- Protecting habitats—especially intact forests and wetlands.

- Controlling invasive species, particularly in island ecosystems.

- Rethinking agriculture, reducing pesticide use and promoting biodiversity-friendly practices.

- Monitoring insects more effectively, using both field surveys and new technologies like acoustic monitoring and genomic analysis.

In Okinawa, for example, researchers are testing acoustic monitoring as part of the Okinawa Environmental Observation Network (OKEON), which could become a model for real-time insect population tracking.

Why This Study Stands Out

This Fiji study is unique because it offers genomic-level proof of long-term decline, rather than just short-term observation. It shows:

- Decline started thousands of years ago, not just recently.

- Human activity is strongly correlated with population collapses.

- Endemic species are far more vulnerable than generalists or non-natives.

In other words, it’s not just about noticing fewer insects today—it’s about uncovering hidden histories of decline stretching back millennia.

Final Thoughts

The disappearance of Fiji’s ants is not an isolated problem. It’s a signal that the Insect Apocalypse is real, global, and already reshaping ecosystems. The fact that 79% of Fiji’s unique ant species are in decline should be a wake-up call for scientists, conservationists, and policymakers worldwide.

While insects are often overlooked compared to large animals, they are essential to keeping ecosystems functioning. Losing them would mean unraveling the very systems that support life on Earth.

This study also reminds us of the power of scientific archives and new technologies. By looking back into museum drawers and extracting hidden genomic clues, researchers have been able to tell a story that would otherwise remain invisible. It’s a sobering reminder that even the smallest creatures can reveal the biggest truths about our planet’s future.

Reference: Genomic signatures indicate biodiversity loss in an endemic island ant fauna (Science, 2025)