Free-Range Dinosaur Parenting May Have Created Surprisingly Diverse Ancient Ecosystems

New research from the University of Maryland is reshaping how scientists think about dinosaurs and the ecosystems they lived in. Instead of behaving like scaled-up versions of modern mammals, many dinosaurs appear to have followed a very different strategy when it came to raising their young. According to this research, that difference in parenting may have played a major role in creating unexpectedly complex and diverse ancient ecosystems.

The study was led by Thomas R. Holtz Jr., a principal lecturer in the Department of Geology at the University of Maryland, and was published in the Italian Journal of Geosciences. Holtz has spent decades studying how dinosaurs fit into their environments, and his latest work challenges a long-standing assumption: that dinosaur-dominated ecosystems were less diverse than modern mammal-dominated ones.

At the center of this rethink is one key idea — how animals raise their young can dramatically shape the ecosystems around them.

Dinosaurs Were Not Just “Mammals With Scales”

For a long time, scientists have tended to compare dinosaurs to modern mammals. Both groups were dominant land animals in their respective eras, and both occupied top positions in food webs. However, Holtz argues that this comparison overlooks a critical difference: reproductive and parenting strategies.

Modern mammals generally invest enormous time and energy into raising their offspring. Young mammals stay with their mothers until they are close to adult size. During that time, they eat similar foods, live in similar habitats, and face similar predators as their parents. As a result, mammal offspring usually occupy the same ecological niche as adults.

Dinosaurs, on the other hand, appear to have taken a very different approach.

Limited Parental Care and Early Independence

Evidence from fossil sites suggests that while many dinosaurs did provide some parental care, it was short-lived. After a few months or, at most, a year, juvenile dinosaurs often became largely independent. Fossil discoveries show groups of young dinosaurs preserved together without adults nearby, indicating that juveniles frequently traveled and lived in groups of similarly aged individuals.

This pattern is supported by comparisons with modern crocodilians, which are among the closest living relatives of dinosaurs. Crocodiles guard their nests and protect hatchlings early on, but within a few months, the young disperse and fend for themselves. It then takes years for them to reach adult size.

In this sense, dinosaurs were more like “latchkey kids” than the heavily supervised offspring of mammals.

Big Broods and High Survival Through Numbers

Another important factor is reproduction. Dinosaurs laid eggs and often produced large broods in a single nesting event. Unlike mammals, which usually have fewer offspring and invest heavily in each one, dinosaurs relied more on numbers. Even if many juveniles were lost to predators or environmental pressures, enough survived to ensure the continuation of the species.

This strategy allowed dinosaurs to increase their chances of long-term survival without the need for prolonged parental investment.

Juveniles and Adults Lived Very Different Lives

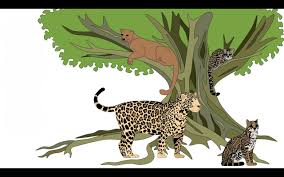

One of the most important ideas in Holtz’s research is ontogenetic niche partitioning. This refers to how an animal’s ecological role changes as it grows.

Dinosaurs often underwent extreme changes in size over their lifetimes. A newborn Brachiosaurus may have been about the size of a golden retriever. As it grew, it passed through stages comparable to a sheep, a horse, a giraffe, and eventually a massive adult towering more than 40 feet tall.

At each stage, what the animal ate, where it lived, and what predators threatened it changed dramatically. A juvenile Brachiosaurus could not reach high vegetation like an adult and had to feed on lower plants. It also faced predators that would never dare attack a fully grown adult.

Because of this, juveniles and adults of the same dinosaur species effectively functioned as different ecological actors, even though they belonged to the same biological species.

Rethinking Diversity in Dinosaur Ecosystems

Traditionally, scientists have believed that modern mammal ecosystems are more diverse than ancient dinosaur ecosystems because they contain more species living together. However, Holtz suggests that this comparison may be misleading.

If juvenile dinosaurs are counted as separate functional species from adults, then dinosaur ecosystems suddenly appear much richer. When recalculated this way, some dinosaur fossil communities may have supported more functional species on average than mammal communities do today.

This does not necessarily mean that dinosaur ecosystems were “better” or objectively more diverse than modern ones. Instead, it suggests that diversity took a different form, one that scientists have not always recognized.

How Could Ancient Ecosystems Support So Many Roles?

Holtz proposes two main explanations for how dinosaur ecosystems could sustain such a wide range of functional niches.

First, environmental conditions during the Mesozoic Era were different. Warmer global temperatures and higher levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide likely made plants more productive. A richer and more productive plant base would have provided more energy to support a larger number of herbivores and, in turn, more predators.

Second, dinosaurs may have had lower metabolic demands than similarly sized mammals. If dinosaurs required less food to survive, ecosystems could support more individuals and more ecological roles without collapsing under resource pressure.

Together, these factors may explain how dinosaur-dominated worlds sustained such complex ecological structures.

What This Means for Paleontology

This research encourages scientists to move away from thinking of dinosaurs as simply mammal stand-ins from a different era. Their biology, life history, and behavior were distinct, and those differences shaped the ancient world in unique ways.

By focusing on functional diversity rather than just species counts, paleontologists can gain a more accurate picture of how ancient ecosystems worked. This approach may also help explain patterns seen in fossil assemblages that previously seemed puzzling or inconsistent.

Holtz plans to continue exploring how changes across dinosaur life stages influenced ecosystems and how those systems eventually transitioned into the mammal-dominated world humans inherited.

A Broader Look at Parenting Strategies in Nature

This research also highlights a broader truth in biology: parenting strategies matter. Whether an animal invests heavily in a few offspring or lightly in many can ripple through entire ecosystems. Similar patterns can be seen today in fish, reptiles, insects, and amphibians, where juvenile and adult stages often occupy very different ecological roles.

Dinosaurs were not just large animals roaming ancient landscapes. They were dynamic participants in ecosystems shaped by growth, change, and independence from an early age.

Understanding that complexity brings scientists one step closer to seeing the ancient world not as a simpler version of our own, but as a system that was different, sophisticated, and surprisingly diverse in its own way.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3301/ijg.2026.09