Fruit Flies’ Embryonic Stage Shows That Climate Adaptation Begins Much Earlier Than We Thought

As global temperatures continue to rise, scientists are increasingly focused on a critical question: how well can living organisms adapt to rapid climate change? A new study from the University of Vermont offers a fresh and important perspective by showing that climate adaptation may begin far earlier in life than scientists once believed — starting at the embryonic stage.

The research centers on the common fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, a species that has long been a cornerstone of genetic and evolutionary research. By examining how fruit fly embryos respond to temperature differences at the genomic level, the study reveals that early life stages can evolve independently from adulthood in response to environmental stress.

Why Scientists Looked at Embryos Instead of Adults

Most previous research on climate adaptation in animals has focused on adult organisms, largely because adults are easier to study and measure. However, this new work challenges that approach by highlighting the importance of early developmental stages, when organisms are especially vulnerable to environmental stress.

Fruit flies are an ideal model for this kind of research. They are found worldwide, experience a wide range of climatic conditions, and have a short life cycle that allows scientists to study multiple generations quickly. Despite this, embryonic stages have often been overlooked, even though embryos cannot escape stressful conditions like extreme heat.

The University of Vermont researchers set out to fill this gap by examining how fruit fly eggs respond to temperature variability — and whether these responses differ based on climate history.

Comparing Tropical and Temperate Fruit Flies

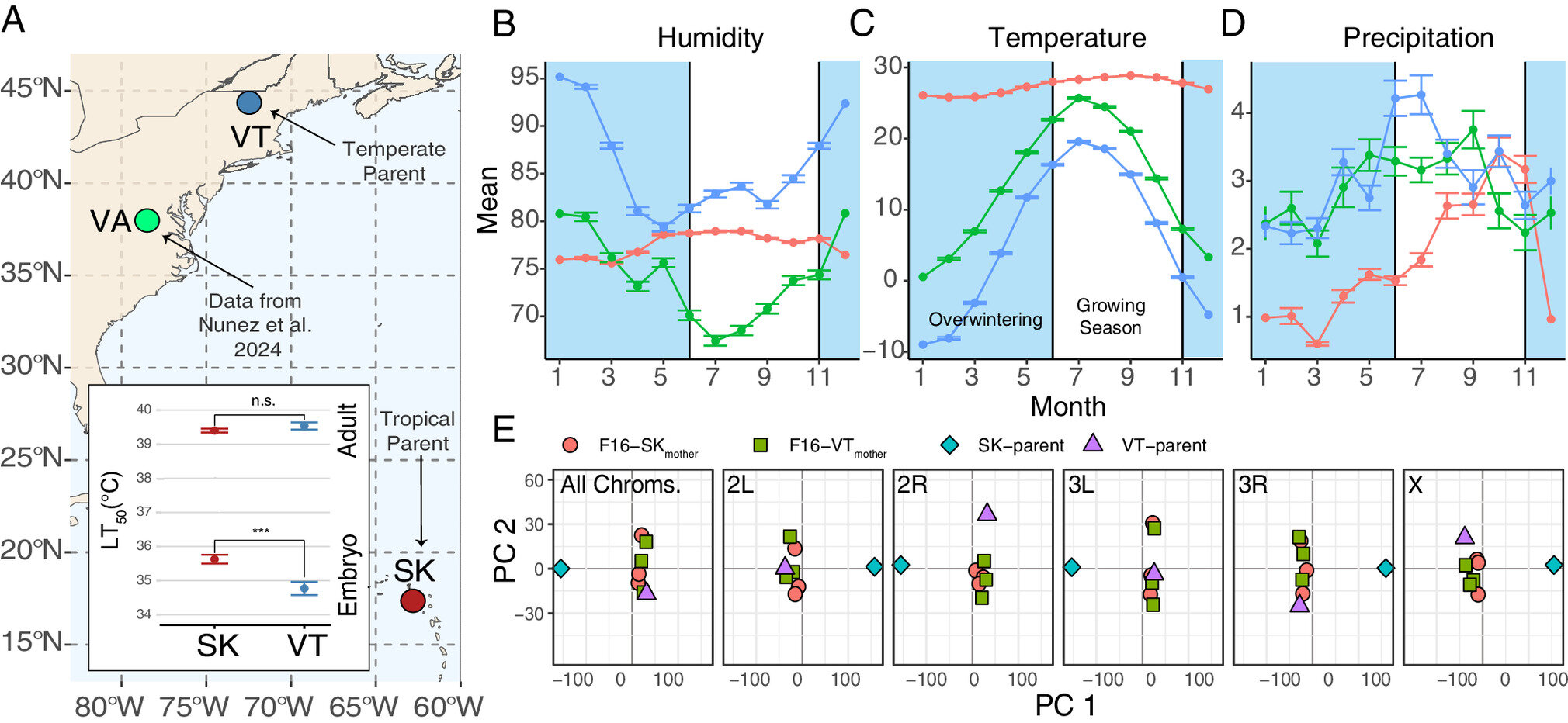

The scientists compared genetically distinct fruit fly populations from different climatic regions in North America. Specifically, they studied flies originating from tropical environments, such as the Caribbean, and temperate regions, including Vermont.

What they found was unexpected. While adult fruit flies showed very little difference in their ability to tolerate extreme heat regardless of where they came from, their eggs told a very different story.

Fruit fly embryos from tropical regions were significantly more heat-tolerant than embryos from cooler, temperate regions. This means that even though adults appear similar in their heat tolerance, early life stages have evolved distinct thermal limits based on local climate conditions.

This discovery highlights a key point: adaptation does not happen uniformly across all life stages.

A Challenge to Long-Held Assumptions in Developmental Genetics

One of the most striking aspects of this study is how it challenges a long-standing belief in developmental biology. For years, scientists assumed that genes controlling embryonic development were highly conserved and unlikely to evolve in response to environmental pressures.

This research shows otherwise.

The genes that make tropical fruit fly embryos more heat-tolerant are also involved in critical developmental processes, including tissue formation and organ development. In other words, genes that shape the body plan of an organism are also adapting to climate conditions.

This finding suggests that developmental genes are not as evolutionarily rigid as once thought. Instead, they can respond to environmental stress while still maintaining essential developmental functions.

Inside the Genomics of Climate Adaptation

To understand what was happening at a genetic level, the researchers combined global genomic datasets, laboratory experiments, and NASA satellite climate data. This allowed them to connect temperature patterns with genetic variation across populations.

The team identified two specific genes that play a role in embryonic heat tolerance. These genes contain regulatory variations that influence how embryos respond to temperature stress during development. Importantly, these are not random genes — they are deeply involved in developmental regulation.

The researchers also conducted principal component analyses across multiple chromosomes, revealing strong genetic differentiation linked to climate. In some cases, over 90% of genetic variance could be explained by a single principal component, underscoring how tightly climate and genetics are connected.

This kind of genomic insight helps explain why embryos from different climates respond so differently, even when adults appear nearly identical.

Why Early Life Stages Matter So Much

Embryos represent a critical bottleneck in the life cycle of many organisms. Unlike adults, embryos cannot behaviorally regulate their temperature by moving to shade or cooler environments. As a result, even short periods of extreme heat can have outsized effects on survival and development.

According to the researchers, there is a narrow developmental window during which organisms establish many of the physiological systems they rely on later in life. If environmental stress affects this window, it can shape not only survival but also long-term evolutionary outcomes.

This means that studies focusing only on adults may miss some of the most important adaptive signals.

Broader Implications Beyond Fruit Flies

Although this study focuses on Drosophila melanogaster, its implications extend far beyond fruit flies. The researchers emphasize that their findings are relevant to any organism with a complex life cycle, including insects, amphibians, plants, and even humans.

Most multicellular organisms develop from an embryo into juvenile and adult stages. If environmental stressors like heat waves influence early development, they may shape evolutionary trajectories across generations.

This raises important questions about how climate change could affect biodiversity, species resilience, and extinction risk — particularly for species whose early life stages are highly sensitive to temperature.

Climate Data Meets Genetics

One of the strengths of this research is its interdisciplinary approach. By combining long-term climate data with genomic analysis and controlled experiments, the scientists created a framework for studying how climate, genetics, and physiology interact.

The study incorporated data on temperature, humidity, and precipitation across multiple years, including overwintering periods for temperate fruit flies. This helped explain why certain populations experience stronger selective pressure during early development.

The researchers believe this approach can be applied to other species and systems, making it a valuable tool for understanding climate adaptation on a broader scale.

What Comes Next for This Research

The research team plans to take their work further in two major ways. First, they want to better understand how the identified genes function during embryonic development, and how changes in gene regulation translate into physiological differences.

Second, they aim to expand their studies to other insect species and beyond, testing whether early-stage climate adaptation is a widespread phenomenon.

As climate change continues to accelerate, understanding these early-life mechanisms may be crucial for predicting which species are most at risk — and which may be more resilient than we expect.

Why This Study Matters Now

This research arrives at a time when climate-driven biological change is no longer theoretical. Heat waves, shifting seasons, and extreme weather events are already reshaping ecosystems worldwide.

By showing that climate adaptation begins at the very start of life, this study adds an important piece to the puzzle. It reminds us that evolution is not just about survival in adulthood — it is also about how life begins under changing environmental conditions.

Research paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2518358123