Future-Focused Conservation Index Reveals Reptiles as the Top Global Priority

A new global study has shed light on which creatures could be at the greatest risk from the growing pressures of climate change, habitat loss, and human expansion — and the results might surprise you. According to scientists from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Israel) and Université Paris-Saclay (France), reptiles — not amphibians — may soon become the group needing the highest conservation priority worldwide.

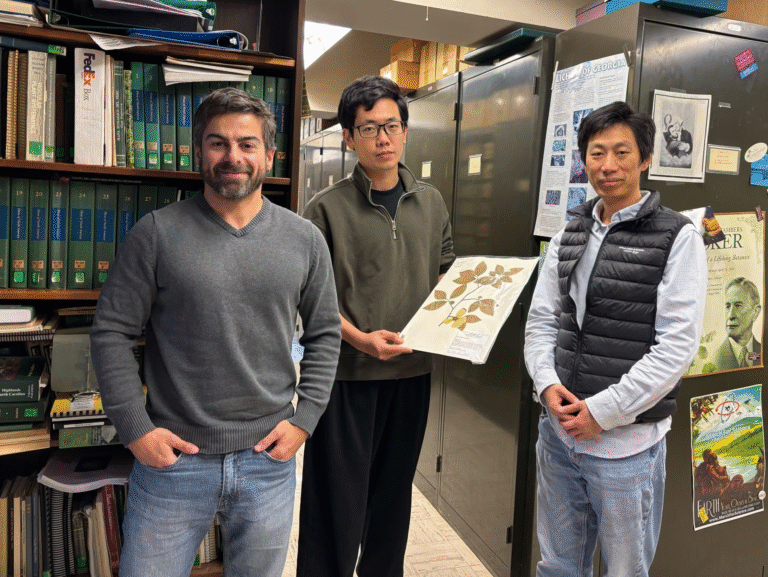

The research team, led by Gabriel Henrique de Oliveira Caetano and colleagues, developed a new analytical tool called the Proactive Conservation Index (PCI), published in PLOS Biology (October 21, 2025). The PCI aims to fill a critical gap in conservation science: most existing systems, including the well-known IUCN Red List, mainly assess past and current threats to species. The PCI, in contrast, looks ahead, forecasting which species are most likely to face serious risks in the coming decades.

What the Proactive Conservation Index (PCI) Does

The PCI was designed to measure how vulnerable different species are to future environmental changes rather than only evaluating their current status. It takes into account a range of future-oriented threats such as:

- Climate change and the intensity of extreme temperature events expected in species’ habitats.

- Land-use change, including how much of their natural environment could be converted for agriculture or urban use.

- Invasive species that could alter native ecosystems.

- Human population growth, which increases pressures like pollution and overexploitation.

To make these predictions more precise, the researchers combined threat data with species-specific traits that influence survival — for example:

- Body size

- Reproductive rate (brood size)

- Geographical range

- Ability to survive in human-modified environments

- Percentage of their range already under protection

Each species was assigned a PCI score between 0 (lowest priority) and 1 (highest priority). This score estimates how urgently a species might require conservation attention in the future, based on how its habitat and resilience interact with global environmental trends.

The analysis included a staggering 33,560 land vertebrate species across the globe — encompassing reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and birds — making it one of the largest assessments of its kind.

Future Scenarios and Data Comparison

To explore different possibilities, the PCI used two Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios:

- SSP2-4.5, a moderate future where climate policies somewhat limit emissions.

- SSP5-8.5, a more extreme scenario representing high emissions and rapid land-use change.

The researchers calculated the PCI for both 2050 and 2100, allowing them to see how species’ risks evolve under moderate and severe futures. They also compared these PCI rankings with the IUCN Red List, the world’s most recognized standard for assessing extinction risk.

The comparison revealed a strong overall correlation between PCI scores and Red List categories. However, there were striking exceptions: in some cases, species currently listed as Least Concern or Data Deficient on the Red List showed high PCI scores, suggesting they might face serious threats in the near future.

Key Findings: Reptiles Take the Spotlight

While amphibians currently hold the unfortunate title of being the most threatened vertebrate group according to the IUCN, the PCI analysis found that reptiles scored higher overall when looking at future risks.

That means in the coming decades, reptiles may surpass amphibians in conservation urgency. The PCI identifies them as the top global conservation priority, especially under the more severe climate and land-use scenarios.

Reptiles — a group that includes lizards, snakes, turtles, and crocodiles — often live in environments such as arid zones, tropical islands, and montane forests. These regions are particularly sensitive to warming, invasive species, and human encroachment.

Some striking examples include species like the Hula painted frog (Latonia nigriventer) from northern Israel. Although an amphibian, it serves as a good case study in the paper because it demonstrates how limited-range species — whether reptile or amphibian — are especially vulnerable when their habitats face simultaneous threats from climate change, land-use change, and biological invasions.

Regions That Need More Focus

The PCI also identifies geographic hotspots that are likely to require intensified conservation efforts in the near future. These include:

- Arid and semi-arid regions, where even small climatic shifts can devastate biodiversity.

- Tropical montane forests, which are rich in species but confined to narrow altitudinal zones.

- Tropical islands, which have unique species found nowhere else on Earth.

Some specific areas that stand out are western India, northern Mexico, the Caribbean, and parts of the Arabian Peninsula. In these places, many reptile species already live on the edge of survival due to small population sizes and limited ranges.

Understanding Why Reptiles Are So Vulnerable

Reptiles are among the most diverse yet underrepresented groups in global conservation discussions. There are over 11,000 known reptile species, but many remain poorly studied compared to mammals or birds.

Their cold-blooded physiology means they rely heavily on environmental temperatures to regulate body heat. As global temperatures rise, reptiles face habitat contraction, reduced reproduction, and even population collapse if they cannot migrate to cooler regions.

Additionally, many reptile species are restricted to small geographic ranges—for example, a single island or desert valley—making them especially vulnerable to land-use change or invasive predators. The pet trade and illegal wildlife trade also disproportionately target reptiles, adding another layer of pressure that isn’t fully captured in large-scale indices like the PCI.

Another challenge is data deficiency: many reptiles are classified as “Data Deficient” on the IUCN Red List because there isn’t enough information about their population trends. The PCI helps bridge this gap by providing predictive risk assessments even for species with limited data.

The Bigger Picture: Why Future-Focused Tools Matter

Conservation has traditionally been a reactive discipline — responding to species once their numbers have already dropped alarmingly. The PCI represents a shift toward proactive conservation, where the focus is on anticipating and preventing future crises.

This approach can make conservation planning more efficient by identifying species that are not yet endangered, but are on a trajectory toward decline. It can also help policymakers direct limited resources to places and species where preventive action will have the greatest impact.

For instance, the study found that protected-area coverage was often negatively correlated with PCI scores — meaning the species with the highest predicted risks tend to live in areas least protected today. By pinpointing these mismatches, conservation managers can prioritize expanding protection where it’s most needed.

Limitations and What Comes Next

While powerful, the PCI isn’t a perfect tool. It doesn’t fully capture localized threats like disease, pollution, or direct exploitation (such as hunting or collection). It also depends on global models of land-use and climate, which come with inherent uncertainties.

Still, the authors argue that the PCI complements, rather than replaces, existing systems like the Red List. Together, they provide a fuller picture of both present and future risks — a crucial step toward truly sustainable biodiversity management.

As global temperatures continue to rise and human activity reshapes landscapes, tools like the PCI will become essential for staying ahead of crises rather than scrambling after them.

Why This Matters for Conservation

Reptiles may not be as charismatic as tigers or elephants, but they play vital roles in ecosystems — controlling pests, dispersing seeds, and maintaining food webs. Losing them would have cascading effects on biodiversity and ecosystem health.

The message of this study is clear: conservation must evolve from merely documenting decline to anticipating it. With a proactive mindset and predictive tools like the PCI, humanity has a better chance of preserving the extraordinary diversity of life on Earth before it’s too late.

Research Reference: The future-focused Proactive Conservation Index highlights unrecognized global priorities for vertebrate conservation, PLOS Biology (2025)