Gene Position in Copepod Chromosomes Shapes How These Tiny Creatures Adapt to Rapid Environmental Change

A new study from researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison has uncovered clear, empirical evidence that the physical location of genes on chromosomes can influence how quickly species adapt. Working with microscopic aquatic crustaceans called copepods—specifically the Eurytemora affinis species complex—the research team mapped millions-year-old chromosomal mutations and showed that these structural changes still shape natural selection today. The work, published in Nature Communications, is significant because it directly links genome architecture to evolutionary adaptability, something scientists have long suspected but rarely demonstrated in living systems.

Understanding Why Copepods Matter

Copepods may be tiny, but they are biologically powerful research subjects. With short lifespans and compact genomes, they offer an efficient way to observe evolutionary processes. These crustaceans originally lived in coastal estuaries, but over the past 80 years they have successfully invaded freshwater ecosystems such as the Great Lakes—mostly through ship ballast water. Their ability to survive dramatic shifts in salinity has made them a model for understanding rapid adaptation.

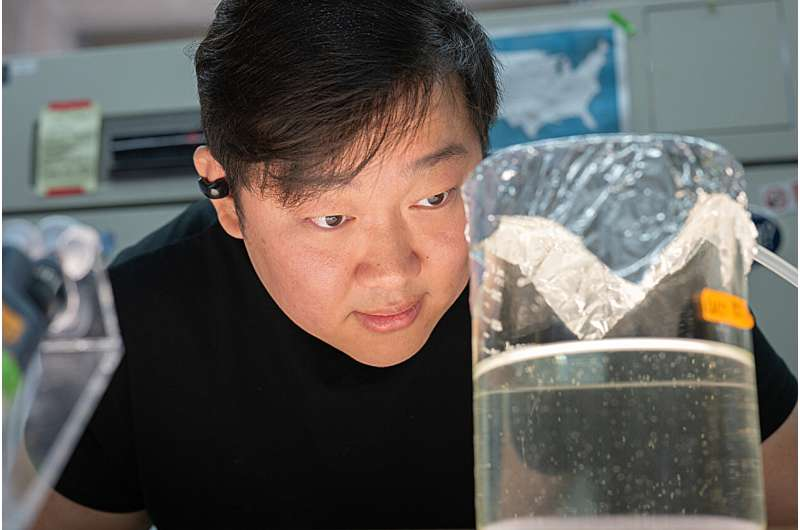

UW–Madison professor Carol Eunmi Lee, who has spent more than two decades studying copepod genetics, led the research alongside postdoctoral scientist Zhenyong Du. Their core question was simple but ambitious: How does the arrangement of genes within the genome affect the way natural selection operates?

The Discovery of Drastically Different Chromosome Numbers

One of the most striking findings of the study is that the three sibling species (or clades) within the Eurytemora affinis complex have entirely different chromosome counts:

- The European clade has 15 chromosomes

- The Gulf clade has 7 chromosomes

- The Atlantic clade—the one now established in the Great Lakes—has only 4 chromosomes

Despite these differences, the clades share a common ancestor and can still interbreed, which is unusual for organisms with mismatched chromosome numbers. Du spent nearly three years generating chromosome-level genome sequences to determine how such drastic structural variations developed and what role they might play in adaptation.

How Chromosomal Fusions Reshaped the Genome

The key mechanism behind these chromosome differences is chromosomal fusion, where two or more chromosomes merge during evolution. These fusions don’t just reduce the total number of chromosomes—they physically relocate genes, often placing them next to genes they were never linked with before.

The researchers found that ancient fusions in these copepods repeatedly brought together clusters of genes involved in ion transport, an essential function for surviving shifts in salinity. Because salinity is the major environmental variable copepods face, grouping these genes could provide a selective advantage.

Why Gene Location on a Chromosome Matters

A major insight from the study is that the fusions didn’t simply group ion-transporter genes—they also moved them closer to the center of chromosomes, away from the recombination-prone chromosome arms.

Recombination occurs when DNA is shuffled during reproduction. While recombination is useful for generating diversity, it can also break apart beneficial clusters of genes. Moving critical gene networks toward the chromosome’s center protects them from recombination, preserving adaptive combinations.

This indicates that natural selection did not just act on the gene variants themselves—it acted on where those genes were positioned.

Ancient Mutations Still Under Selection Today

Even more surprising, the study revealed that fusion sites created millions of years ago remain active hotspots of natural selection in modern populations, especially within the invasive Atlantic clade. When comparing freshwater and saline populations, the researchers found clear signs that these genomic regions are still shaping evolutionary responses.

This means the genomic architecture created long before modern ecological changes continues to influence how copepods adapt to new environments—including those altered by human activity.

What This Means for Evolutionary Biology

The findings provide the first solid empirical support for a longstanding theory: chromosomal structure can directly influence evolutionary potential. Scientists have hypothesized for decades that genome architecture plays a role in adaptation, but evidence has been limited. This study fills that gap.

The work suggests that structural mutations such as chromosomal fusions may be powerful tools for speeding adaptation by:

- Linking related genes into inherited units

- Reducing recombination around beneficial gene clusters

- Stabilizing adaptive traits across generations

This could help explain why certain invasive species rapidly evolve tolerance to new environments.

Broader Implications for Other Species and Climate Change

Although this research focuses on copepods, the implications extend far beyond aquatic microcrustaceans. Many species—from insects to fish to plants—experience genome rearrangements over evolutionary time. The study suggests that these rearrangements are not random quirks but potentially major drivers of adaptability.

Understanding genome architecture could improve predictions about:

- Which species are likely to thrive under rapid climate change

- How invasive species develop resilience to new environments

- Why some populations evolve faster than others despite similar genetic variation

Because genome structure affects how natural selection works, two species with similar gene content may evolve at very different speeds depending on how their genomes are organized.

Additional Background: What Are Chromosomal Fusions?

To give readers a clearer picture, chromosomal fusions occur when two chromosomes join together, often after breaks in DNA. These events can be:

- Robertsonian fusions, where whole chromosome arms fuse

- End-to-end fusions, where telomeres join directly

- Complex rearrangements, involving multiple breakpoints

In animals, chromosomal fusion events have been documented in rodents, primates (including evolution leading to human chromosome 2), and many insect species. Such events can create reproductive barriers but can also enable major evolutionary leaps if they stabilize beneficial gene clusters.

Why Ion Transporter Genes Are So Important

Copepods regulate their salt balance through a suite of specialized proteins called ion transporters. Different water environments require careful control of sodium, chloride, and other ions. When copepods move from salty estuaries into freshwater, they must rapidly adjust to avoid losing essential salts to the environment.

Because these genes are key to survival in varying salinity conditions, grouping them together and protecting them from recombination likely provides a strong selective advantage.

A Clear Step Forward in Understanding Adaptation

In sum, the UW–Madison study shows that:

- Genome architecture evolves, not just gene sequences

- Structural changes influence how natural selection acts

- Ancient chromosomal fusions still shape modern adaptation

- Copepods offer a powerful model for studying rapid evolution

The research opens a new dimension in evolutionary biology, emphasizing that where a gene sits may be just as important as what the gene does.

Research Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65292-z