Global Conservation Policy Adopted to Protect Earth’s Old, Wise, and Large Animals

In a remarkable move for global biodiversity, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has officially adopted a new global policy known as “Longevity Conservation” — a concept focused on protecting the oldest, largest, and most experienced animals on Earth. The motion, formally called Motion 113, was passed at the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi, with overwhelming international support from governments, NGOs, and scientists.

This policy stems from a Charles Darwin University (CDU)-led research project, later published in Science in 2024, titled “Loss of Earth’s old, wise, and large animals.” The study laid the groundwork for the idea that older individuals within animal populations play critical ecological and social roles — and that conserving them is vital for maintaining the natural balance of ecosystems.

What Is Longevity Conservation?

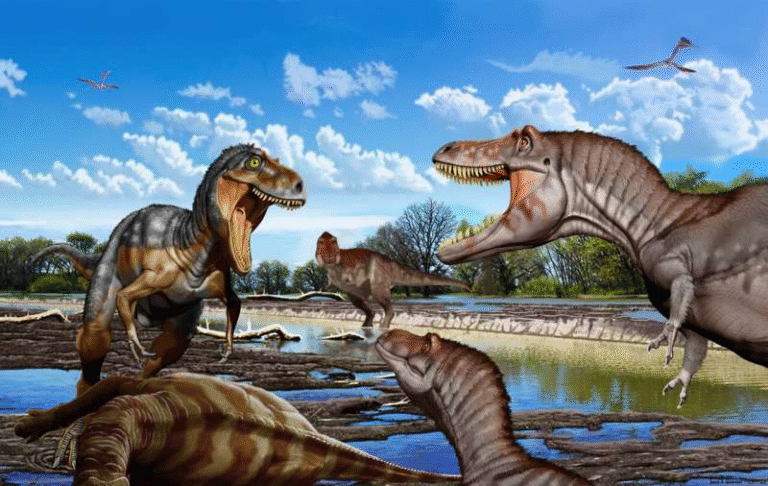

Longevity Conservation is a new framework that focuses not just on saving species from extinction, but also on protecting the age diversity within those species. Most conservation efforts look at how many animals exist, but rarely at how old they are. This new approach argues that without older individuals, ecosystems lose stability, knowledge, and resilience.

Older animals often act as leaders, guides, and knowledge-keepers. In species such as elephants, whales, and wolves, older members remember migration routes, food sources, and survival strategies that younger ones learn from. In fish populations, large and old individuals produce more eggs and help maintain population stability. Losing them, therefore, means more than losing numbers — it means losing wisdom built through generations of experience.

The new IUCN policy commits member countries and conservation organizations to explicitly include age structure in their biodiversity and wildlife management plans.

Key Points of Motion 113

The Motion 113 resolution, titled “Strengthening planning for preserving biodiversity through the use of Longevity Conservation approaches to ensure naturally age-structured populations of species,” outlines several clear goals and responsibilities:

- Develop monitoring and research frameworks to assess the age structure of animal populations and ensure they mirror natural conditions.

- Implement management strategies that explicitly protect older individuals, not just the species as a whole.

- Integrate age diversity into conservation and resource-use policies, including fisheries, wildlife protection, and sustainable development programs.

The motion also encourages age- and size-based harvest regulations, catch-and-release strategies, protected migration corridors, and interconnected protected areas to help older animals survive longer and continue contributing to their ecosystems.

Why Older Animals Matter

This concept may seem simple, but it challenges decades of traditional wildlife management. Historically, older individuals have often been ignored in conservation discussions or even viewed as less productive. But the CDU-led research highlights how deeply this perspective underestimates their importance.

Older animals are ecological anchors. They stabilize population dynamics, guide migrations, maintain reproductive patterns, and help preserve social order within animal communities. Removing them through poaching, overfishing, trophy hunting, or habitat loss leads to age truncation — when populations become unnaturally young.

Age-truncated populations tend to reproduce unpredictably, become more vulnerable to diseases, and struggle to adapt to climate change. They lose the “elders” who remember where to migrate during droughts or where to find shelter during storms.

In elephants, for example, matriarchs often lead herds through decades-old migration paths known only to them. In orcas, grandmothers guide pods to food sources even in lean years. In many bird species, older individuals influence breeding success and territory stability. Removing them destabilizes entire systems.

Global Collaboration and the Research Behind It

The Science paper that inspired the motion was led by Dr. R. Keller Kopf of Charles Darwin University’s Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods. It brought together scientists from the University of Exeter, Charles Sturt University, Macquarie University, the Amboseli Trust for Elephants (Kenya), the University of Stirling, and Texas A&M University.

The study showed that human activities — especially overharvesting, poaching, and environmental degradation — disproportionately remove older individuals from the population. This loss has ripple effects that go far beyond immediate numbers, altering food webs, reproduction patterns, and even cultural knowledge transfer in species that exhibit social learning.

Following publication, Dr. Kopf and his team worked closely with international partners and conservation groups to push the concept forward to the global policy level. Their advocacy eventually resulted in Motion 113’s adoption by IUCN, marking a major milestone in how conservation science informs policy.

Connection to Broader Global Goals

The Longevity Conservation motion doesn’t stand alone — it fits within major global frameworks, including:

- The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to halt biodiversity loss and promote sustainable ecosystems.

- The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted under the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2022, emphasizing ecosystem restoration and protection of species diversity.

- National conservation strategies, such as Australia’s Threatened Species Strategy, which may integrate longevity principles into future policies.

By aligning with these frameworks, Longevity Conservation ensures that protecting older animals becomes a recognized part of international biodiversity planning.

The Path Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

While the policy adoption is a huge step forward, scientists stress that implementation will be the true test. Protecting older animals requires new ways of monitoring populations — not just counting individuals but also identifying their age distribution.

In fisheries, this could mean limiting the capture of the largest fish that are often the most fertile. In wildlife management, it might involve redefining hunting quotas to prevent targeting dominant or mature animals. For migratory species, cross-border cooperation will be essential to protect elders that travel vast distances.

These steps will demand better data, collaboration between researchers and governments, and long-term commitment from conservation organizations.

Beyond Animals: What About Ancient Trees?

Interestingly, the Longevity Conservation concept also has implications for old-growth trees. Just as old animals are vital for ecosystems, ancient trees serve as crucial carbon sinks, habitats, and sources of genetic diversity. Protecting them alongside old animals creates a broader philosophy of respecting biological longevity — the idea that “the old” in nature often hold the key to resilience.

In forests, ancient trees stabilize soil, regulate water flow, and house countless species. Their protection mirrors the same principles guiding the Longevity Conservation approach for animals.

Why This Policy Matters for the Future

The adoption of Motion 113 signals a growing recognition that biodiversity is not just about numbers — it’s about structure, function, and legacy. By acknowledging the importance of older individuals, the IUCN has broadened the way conservation is defined.

It’s a shift from merely saving species from extinction to preserving their wisdom, stability, and continuity. In a world where many species face increasing threats, this approach adds a new layer of protection rooted in both science and respect for the natural order of life.

The Charles Darwin University team and its partners hope that governments and conservation groups worldwide will now begin building strategies to apply these longevity principles in real-world management. From marine reserves to elephant sanctuaries, the message is clear: to protect the future, we must also protect the old.

Research Reference: Loss of Earth’s old, wise, and large animals – Science (2024)