Golden Eagles in the Western US Appear Stable but Nevada’s Population Is Quietly Declining

Golden Eagles have long been considered one of North America’s most resilient and iconic birds of prey. Protected under federal law since 1962, these powerful raptors are often cited as a conservation success story in the western United States, where overall populations are generally described as stable. However, new scientific research shows that this reassuring picture does not apply everywhere. In Nevada, Golden Eagles may be facing a far more serious situation than previously understood.

A recent study published in the Journal of Raptor Research reveals that Nevada’s Golden Eagle population is likely declining and may even function as what ecologists call a population sink. This means that local survival and reproduction rates are too low to sustain the population without constant reinforcement from birds arriving from other regions. While nesting territories across the state still appear occupied, the underlying dynamics suggest a troubling long-term outlook.

Understanding what is happening in Nevada requires looking beyond surface-level indicators and examining how survival, mortality, habitat quality, and human activity intersect across the landscape.

What the Study Examined and Why It Matters

The study, titled “Estimating Survival and Population Trajectories of Golden Eagles in Nevada,” was led by researchers from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and partner institutions. Unlike many previous assessments that focused mainly on adult breeding birds, this research took a broader approach by including nonbreeding individuals, often referred to as “floaters.”

Floaters are adult or subadult eagles that are capable of breeding but do not currently hold a nesting territory. They play a crucial role in population dynamics because they can quickly fill vacant territories when breeding adults die. This can make populations appear stable even when death rates are unsustainably high.

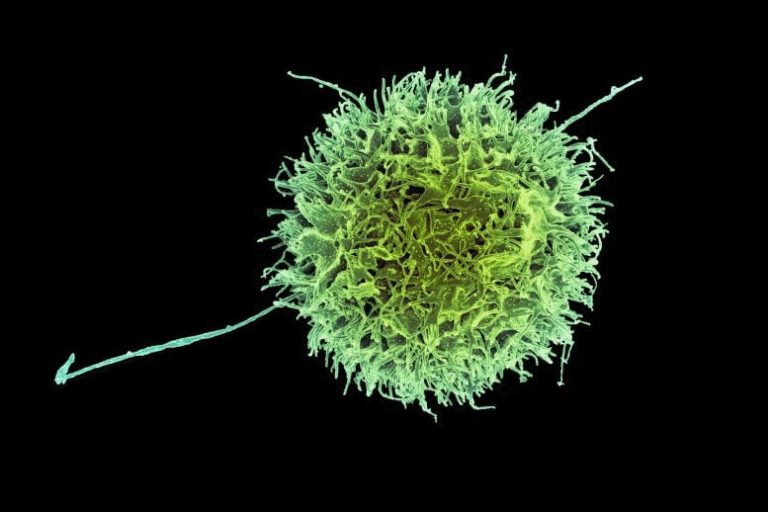

To better understand survival patterns, researchers captured and tagged 43 Golden Eagles—both adults and subadults—between 2014 and 2024. These birds were tracked across Nevada’s Great Basin and Mojave Desert regions, areas that support a significant portion of the western Golden Eagle population and include large stretches of threatened sagebrush steppe habitat.

The data collected from these tagged birds were then fed into population models designed to predict long-term trends. The results raised serious concerns.

High Mortality Rates Across All Ages

One of the most striking findings of the study was the high mortality rate among the tracked eagles. Out of the 43 birds monitored, at least 30 died during the study period. This represents a loss rate that is far too high to support a self-sustaining population.

The causes of death were varied but heavily linked to human activity and environmental stress. Documented causes included electrocution on power lines, collisions with vehicles and human-made structures, and starvation. Starvation, in particular, points to broader ecological problems rather than isolated incidents.

What surprised researchers most was that these elevated death rates occurred across multiple age classes, not just among younger, inexperienced birds. Adult eagles, which are typically the backbone of population stability, were also dying at concerning rates.

Why Territories Still Look Occupied

Despite these losses, Golden Eagle territories across Nevada remained consistently occupied throughout the study period. At first glance, this would suggest a healthy population. However, this apparent stability may be misleading.

The study suggests that many of these territories are being filled by immigrant eagles from outside Nevada, as well as by floaters that step in when resident birds die. In other words, the population is being propped up by birds drawn in from elsewhere, only to face the same dangers once they arrive.

This creates a dangerous feedback loop. As long as new birds keep arriving, nesting territories remain occupied, masking the underlying decline. Over time, however, this process can drain surrounding populations and lead to broader regional impacts.

Nevada’s Role as a Potential Population Sink

The concept of a population sink is central to understanding the significance of these findings. A sink does not necessarily look unhealthy at first glance. Birds may be present, nests may be active, and breeding may still occur. The problem lies in the balance between births and deaths.

In Nevada, deaths appear to outpace successful recruitment of young birds into the breeding population. Without constant immigration, the local population would likely collapse. Population sinks are especially concerning because they draw individuals from a much larger area, potentially weakening populations far beyond the boundaries of the sink itself.

Environmental Pressures on Golden Eagles in Nevada

Several overlapping pressures are contributing to Nevada’s challenging conditions for Golden Eagles.

One major factor is habitat loss and degradation. Nevada is among the top states in the US for potential solar and geothermal energy development. While renewable energy is critical for addressing climate change, large-scale projects can fragment habitat, disrupt prey populations, and increase collision risks if not carefully planned.

Golden Eagles in Nevada also depend heavily on rabbits, particularly jackrabbits, as a primary food source. Since 2020, rabbit populations have declined sharply due to rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (RHDV2). Combined with prolonged drought conditions, this has reduced food availability and increased the risk of starvation, especially for younger birds.

Wildfires, expanding mining operations, and long-term climate stress further complicate the picture by altering vegetation patterns and reducing the quality of hunting grounds.

Why Nonbreeding Eagles Deserve More Attention

One of the study’s most important contributions is its emphasis on nonbreeding Golden Eagles. Traditional monitoring often focuses on occupied nests and breeding success, which can miss early warning signs of decline.

Floaters are notoriously difficult to detect and track, yet they are essential for understanding population resilience. A shrinking floater pool means fewer birds are available to replace lost breeders, making populations more vulnerable to sudden crashes.

By including nonbreeding individuals, the researchers were able to reveal population dynamics that would otherwise remain hidden.

Conservation Priorities Moving Forward

The researchers identify habitat conservation as the most critical management action for protecting Golden Eagles in Nevada. Maintaining large, connected landscapes with healthy prey populations is essential for improving survival rates.

Encouragingly, there is evidence that careful collaboration with developers can reduce impacts. Adjusting the placement of infrastructure, preserving key hunting areas, and minimizing disturbance near nests can make a meaningful difference.

The study also highlights the need for fine-scale population monitoring that includes both breeding and nonbreeding birds. Without this level of detail, population sinks can persist unnoticed until declines become severe.

Additional Context About Golden Eagles

Golden Eagles are among the most widely distributed raptors in the world, occupying habitats across North America, Europe, Asia, and parts of Africa. They are apex predators with slow life histories, meaning they mature late, produce relatively few offspring, and rely on high adult survival to maintain stable populations.

This life strategy makes them especially vulnerable to sustained increases in adult mortality. Even small increases in death rates can have large long-term effects, particularly in regions already facing environmental stress.

While Golden Eagles are resilient and adaptable, this study shows that resilience has limits.

Research Reference

Estimating Survival and Population Trajectories of Golden Eagles in Nevada

Journal of Raptor Research (2025)

https://doi.org/10.3356/jrr2521