How a Parasite Gave Up Sex to Infect More Hosts and Why That Advantage May Not Last

Australian researchers have uncovered a fascinating and slightly unsettling evolutionary shortcut taken by a common parasite—one that briefly helped it infect more hosts by abandoning sexual reproduction, but may ultimately lead to its downfall. The discovery offers fresh insight into how parasitic infections spread, how zoonotic diseases emerge, and why some pathogens become resistant to treatment.

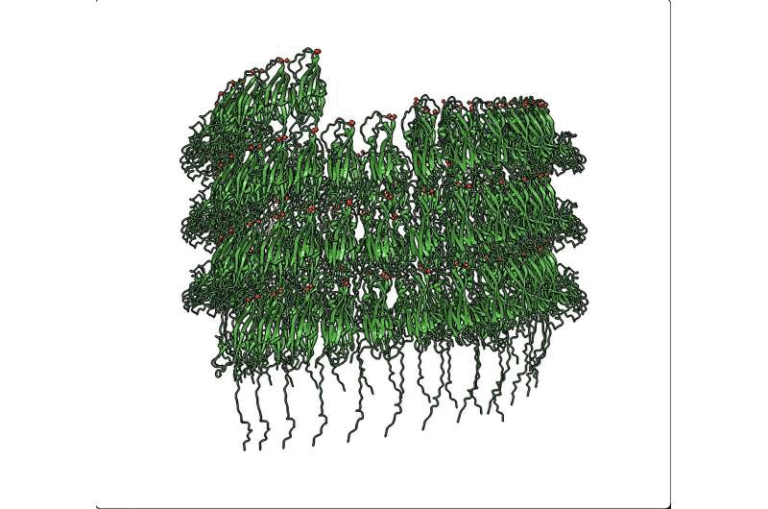

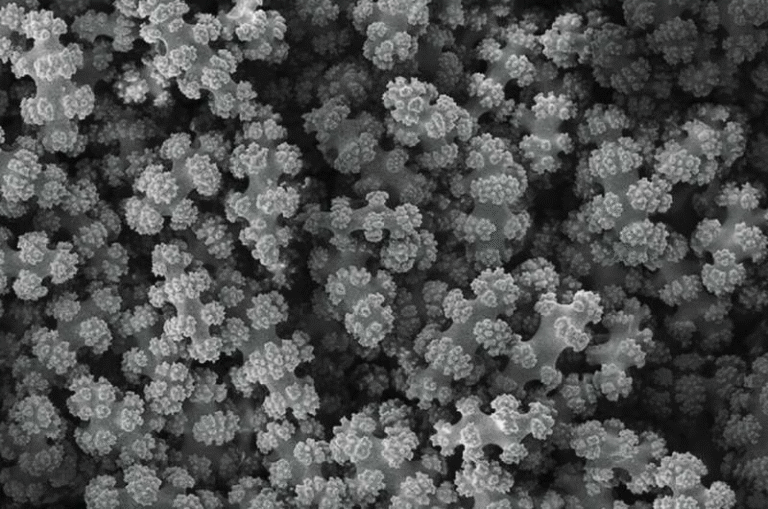

The study focuses on Giardia duodenalis, a microscopic parasite responsible for giardiasis, a diarrheal disease that affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide. While Giardia has long been a public health concern, this new research sheds light on how certain strains manage to jump between species more easily than others—and what that means for long-term survival and disease control.

A Parasite with a Global Impact

Giardiasis is far from a minor illness. The disease interferes with nutrient absorption in the small intestine, often leading to chronic diarrhea, fatigue, and growth delays in children. In severe or prolonged cases, it can contribute to malnutrition, particularly in vulnerable populations.

One of the reasons Giardia is so difficult to control is its ability to form hardy cysts. These cysts can survive for long periods in water and the environment, making outbreaks stubbornly persistent. Contaminated drinking water, poor sanitation, and close contact with infected animals all contribute to its spread.

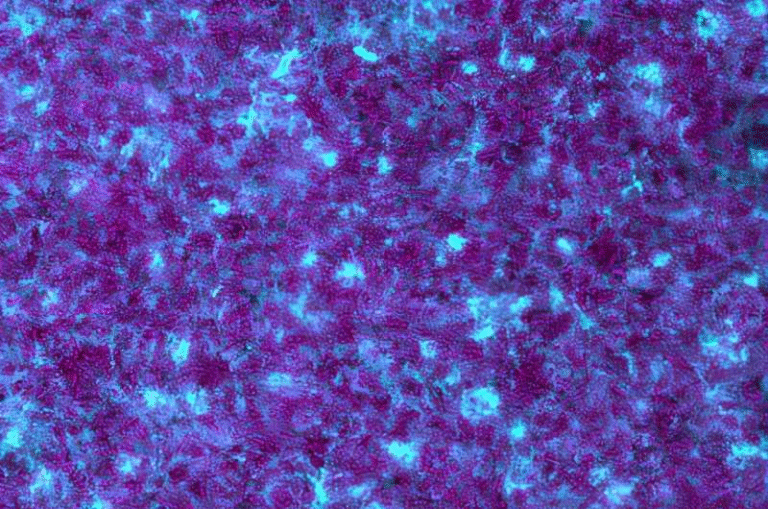

The scale of the problem is significant. In Australia alone, there are up to 600,000 cases of giardiasis every year. Globally, the number exceeds 280 million cases annually. The disease hits hardest in poorer communities and has a disproportionate impact on children and remote Indigenous communities in Australia, where access to clean water and healthcare can be limited.

A Genetic Shortcut with Consequences

The new research, led by scientists at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI), uncovered an unusual evolutionary pattern in Giardia. The team identified an asexual lineage of the parasite that has managed to infect a much wider range of hosts than its sexually reproducing relatives.

This lineage appears capable of infecting pets, livestock, wildlife, and humans, making it far more versatile than strains adapted to a single host species. This ability, known as host range expansion, is a key factor in how new infections emerge and spread to people.

What makes this finding surprising is that sexual reproduction is usually considered an evolutionary advantage. Sex allows organisms to reshuffle their genes, helping them adapt to changing environments and fight off harmful mutations. By contrast, asexual organisms are expected to accumulate genetic damage over time.

Yet in this case, giving up sex seems to have provided a short-term advantage.

Survival of the “Fit-ish”

The study revealed that the asexual Giardia lineage likely arose relatively recently and is already showing signs of genetic decline. This process is explained by a well-known evolutionary mechanism called Muller’s Ratchet.

Muller’s Ratchet describes how, in asexual populations, harmful mutations build up over generations because there is no genetic recombination to remove them. Once a mutation appears, it tends to stick around. Over time, this can lead to what scientists call mutational meltdown, where the organism becomes less viable and eventually collapses.

Paradoxically, this genetic decay may have helped Giardia become a generalist. As the parasite lost some of its finely tuned adaptations to a specific host, it became less specialized but more flexible, allowing it to infect a broader range of species.

Rather than “survival of the fittest,” the researchers describe this as survival of the fit-ish. The parasite is not optimally adapted, but it is good enough to spread quickly into new hosts before the long-term genetic costs catch up.

Why This Victory Is Temporary

While the ability to infect many hosts offers a clear advantage in the short term, the study suggests it comes with a steep price. Without sexual reproduction, the asexual Giardia lineage cannot effectively purge harmful mutations. Over time, these mutations accumulate, reducing the parasite’s overall fitness.

In evolutionary terms, this means the lineage is likely heading toward extinction, even as it spreads more widely in the present. The very shortcut that allows it to thrive now may ensure it cannot survive in the long run.

This trade-off helps explain why sexual reproduction remains so widespread in nature, despite its costs. Sex is not just about reproduction—it is about long-term survival in an evolutionary arms race against hosts, immune systems, and environmental pressures.

Implications for Zoonotic Disease Spread

Host switching—the ability of a pathogen to jump between species—is one of the biggest drivers of emerging infectious diseases. When a parasite expands beyond a single host, controlling outbreaks becomes far more difficult.

Understanding the genetic patterns behind host range expansion could help public health experts anticipate zoonotic spillover before it becomes entrenched. By identifying strains that are more likely to infect multiple species, surveillance efforts can be more targeted and effective.

This is particularly important in a world where human, animal, and environmental health are increasingly interconnected.

A Hidden Pathway to Drug Resistance

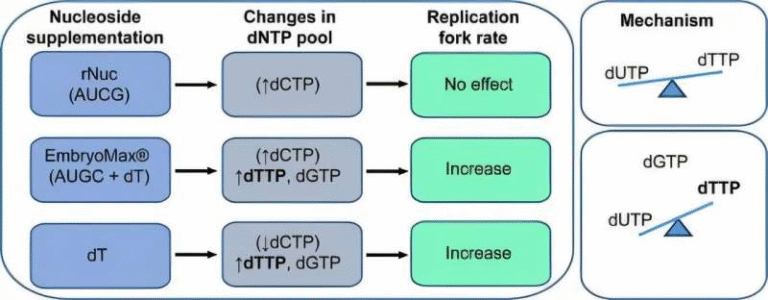

The findings may also help explain how drug resistance emerges and persists in parasitic infections.

Mutations that allow parasites to survive drug treatment often come with downsides, making the organism weaker overall. In sexually reproducing populations, these mutants are typically outcompeted by healthier strains.

In asexual parasites, however, selection becomes inefficient. Harmful mutations are not easily removed, allowing drug-resistant strains to linger and spread, even if they are less fit overall. This creates a window of opportunity for resistance to take hold and circulate.

The same genetic shortcut that enables host switching may therefore also contribute to the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance, with serious implications for treatment strategies.

Why Parasite Sex Still Matters

This research highlights an often-overlooked point: sex plays a crucial role in maintaining genetic health. For parasites, sexual recombination helps them keep pace with host defenses and environmental changes.

When sex stops, short-term gains—like infecting new hosts or surviving drug treatment—can come at the cost of long-term viability. The Giardia study raises new questions about how similar mechanisms might operate in other parasites and pathogens that threaten human health.

What Comes Next

The researchers plan to investigate whether the same genetic shortcuts that allow parasites to switch hosts also enable drug-resistant strains to persist. If so, this knowledge could guide smarter surveillance systems and treatment strategies designed to stop outbreaks before they start.

By understanding not just how parasites spread, but why certain strategies succeed or fail over time, scientists hope to stay one step ahead in the ongoing battle against infectious disease.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65843-4