How Cancer Cells Manage Missing Chromosomes and Maintain Protein Balance

Cancer cells are known for their chaotic genetics, and one of the most striking features is aneuploidy, a condition where cells carry an abnormal number of chromosomes or chromosome arms. While this imbalance is generally harmful to normal cells, up to 90% of tumors display some form of aneuploidy. A new study led by researchers from Yale and Columbia takes a closer look at how cancer cells cope when they are missing parts of chromosomes—especially the 3p arm of chromosome 3, which is commonly lost in several cancers, including lung squamous cell carcinoma. The findings reveal a surprising, previously overlooked strategy that cancer cells use to survive despite such genetic losses.

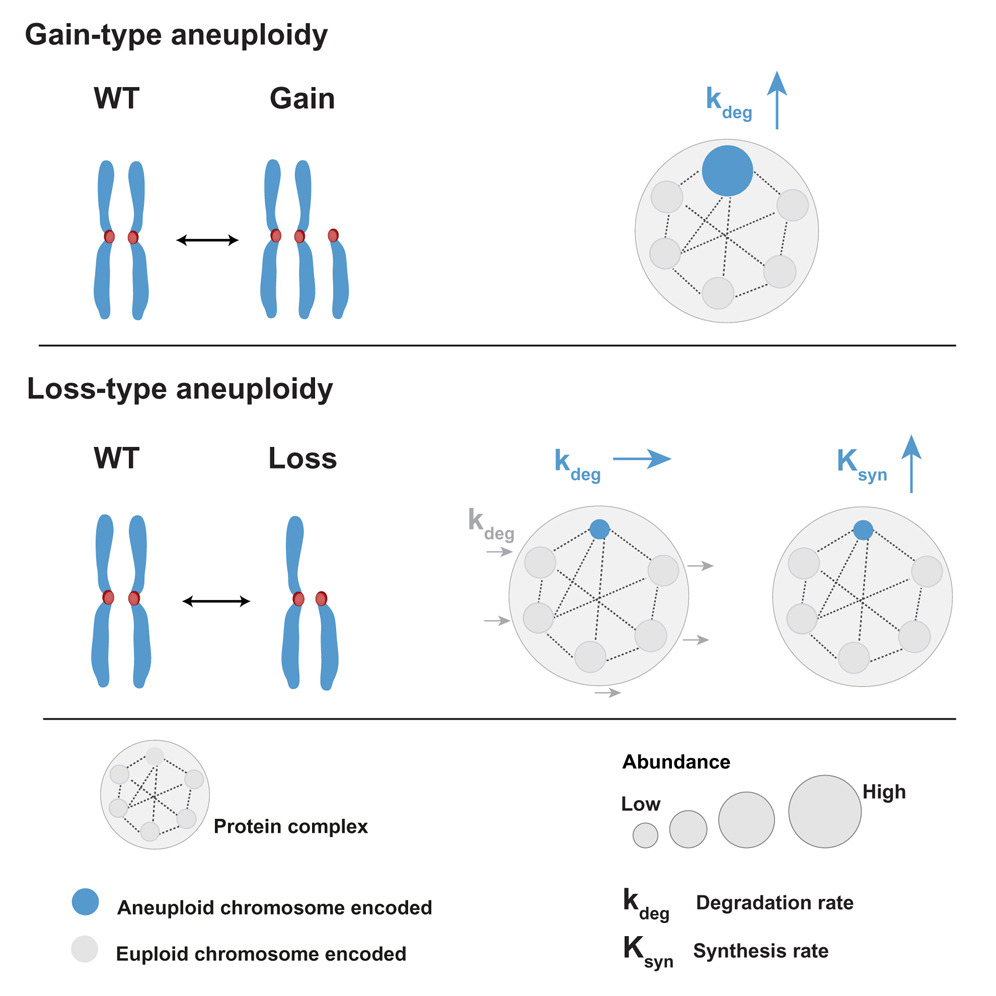

This research builds upon earlier work from the same group that studied cells with extra chromosomes, such as in trisomy 21, where excess proteins must be managed. That earlier work pointed to one dominant mechanism: cells increase the degradation of proteins produced by the extra chromosome to prevent potentially toxic buildup. But when it comes to missing chromosomes, the new study shows that the story is entirely different.

Understanding Aneuploidy and Why It Matters

Aneuploidy disrupts the balance of DNA, and since DNA encodes the instructions for making proteins, any gain or loss of chromosomes affects protein levels. Proteins drive countless cellular processes, so keeping them in proper proportion—known as proteostasis—is essential for survival.

For a long time, the scientific community assumed that cells maintain proteostasis mainly by adjusting protein degradation rates. If too many proteins appear, cells degrade them faster; if too few exist, cells slow degradation down. This seemed to be a sensible solution.

However, cancer cells appear to defy this simplicity. They not only survive chromosome loss but often leverage it to gain an advantage. Understanding how they do this could help identify new therapeutic opportunities.

Earlier Findings on Extra Chromosomes

During prior work at ETH Zurich, the research team used mass spectrometry to examine how cells with trisomy 21 adjust to having an extra chromosome. They found that cells significantly increase protein degradation for proteins encoded on chromosome 21. This supported the prevailing view that degradation is the cell’s main regulatory tool when managing protein imbalance.

Focusing on Chromosome Loss in Cancer

In many cancers, including lung cancer, both gains and losses of chromosome arms occur simultaneously. For example, in lung squamous cell carcinoma:

- Over 60% of tumors show an extra 3q arm.

- Around 80% of those same tumors are missing the 3p arm.

This combination—gain of 3q and loss of 3p—suggests that cancer cells navigate a complex balancing act. But what mechanisms allow them to tolerate missing genetic material?

To examine this question, the team collaborated with researchers at Columbia University to create precise models of human lung epithelial cells with:

- A deleted 3p arm,

- An added 3q arm, and

- Normal chromosomes for comparison.

This was achieved using CRISPR gene-editing, allowing the team to engineer and study these specific aneuploid conditions in controlled settings.

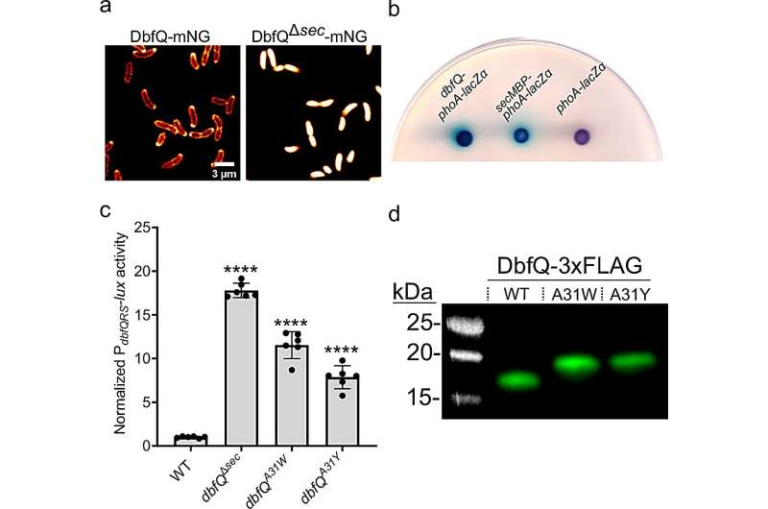

What Happens When Cells Gain 3q

Using advanced mass spectrometry tools, the researchers quantified protein abundance, synthesis, and degradation across the engineered cell lines.

Cells with an extra 3q arm behaved as expected. They showed:

- Increased degradation of proteins encoded on 3q

- A clear effort to maintain relative protein proportions

This aligned well with earlier studies and common assumptions about how cells handle chromosome gains.

The Surprising Strategy for 3p Loss

When the team analyzed cells missing the 3p arm, they expected to observe adjustments in protein degradation. Their predictions were:

- Either reduced degradation of proteins encoded by 3p

- Or increased degradation of all other proteins to retain balance

Neither turned out to be true.

Instead, the data showed no significant change in protein degradation rates at all—neither up nor down.

The real discovery was this:

Cells compensate for missing chromosomes by increasing protein synthesis, not decreasing degradation.

Specifically, cells accelerate the synthesis of proteins encoded by the missing 3p region. This selective boost allows them to restore the protein levels that would otherwise drop due to missing DNA.

This mechanism stands in direct contrast to compensation for extra chromosomes, highlighting a divergent strategy depending on whether genetic material is gained or lost.

The team validated this surprising mechanism through both:

- Protein-based measurements, and

- RNA-based measurements, which showed elevated transcription of genes tied to missing chromosome regions

Thus, the conclusion is firm: protein synthesis—not protein degradation—is the key compensation method for loss-type aneuploidy.

Thermostability as a Clue

Another intriguing finding emerged from examining thermostability of proteins associated with 3p. These proteins showed significantly higher melting points, meaning they are more stable under heat and may remain folded and functional longer. This could help cells maintain essential processes even when chromosome loss disrupts the genetic template.

Thermostability might therefore represent a built-in evolutionary buffer, protecting cells from severe consequences of losing entire chromosome arms.

Broader Implications for Cancer Biology

Understanding how cancer cells adapt to aneuploidy gives researchers new perspectives on tumor survival strategies. Because both overproduced and underproduced proteins can be harmful, cancer cells must constantly fine-tune their internal chemistry.

This study demonstrates that:

- The mechanisms for tolerating chromosome gain and chromosome loss are not the same,

- Loss-type aneuploidy depends heavily on boosted protein synthesis,

- These adaptations can reveal vulnerabilities that future therapies may target.

Targeting proteins or pathways uniquely affected by aneuploidy may open the door to more precise cancer treatments.

Additional Insight: Why Aneuploidy Plays Such a Big Role in Cancer

Beyond the specifics of this study, it helps to understand why aneuploidy is so deeply linked with cancer:

- Aneuploid cells generate genetic and metabolic stress, which can drive mutation and evolution within tumors.

- Some chromosome arms carry tumor suppressor genes, and losing them may accelerate cancer progression.

- Others contain oncogenes, and gaining extra copies can push cells into uncontrolled growth.

Because chromosome arms contain hundreds of genes, even the gain or loss of a single arm can dramatically reshape a cell’s behavior. Many cancers feature characteristic aneuploid patterns—such as the 3p loss and 3q gain combination investigated in this study—indicating that these imbalances offer selective advantages.

Why Protein Balance Matters

Cells rely on thousands of interconnected proteins. Losing or gaining large chunks of the genome disrupts these networks. To survive, cells must maintain:

- Absolute protein levels (how much of each protein exists)

- Relative levels (how proteins interact in complexes)

If levels drift too far out of balance, proteins misfold, pathways break, and the cell can die. Cancer cells’ ability to actively reshape protein synthesis and degradation helps them stay operational despite highly abnormal genomes.

This study adds valuable clarity to how these adjustments work, especially in the case of chromosome loss.

Study Reference

Divergent proteome tolerance against gain and loss of chromosome arms – https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2025.10.023