How Cells Pause, Reorganize, and Restart Gene Activity During Stress

All living cells constantly sense their surroundings and adjust their behavior to survive. Changes in temperature, lack of nutrients, or other environmental shocks can disrupt normal cellular activity. One of the most fascinating responses to these challenges is how cells temporarily pause ongoing work, reorganize their internal machinery, and then restart when conditions improve. New research published in Molecular Cell reveals that cells do this in a far more organized and intentional way than scientists once believed.

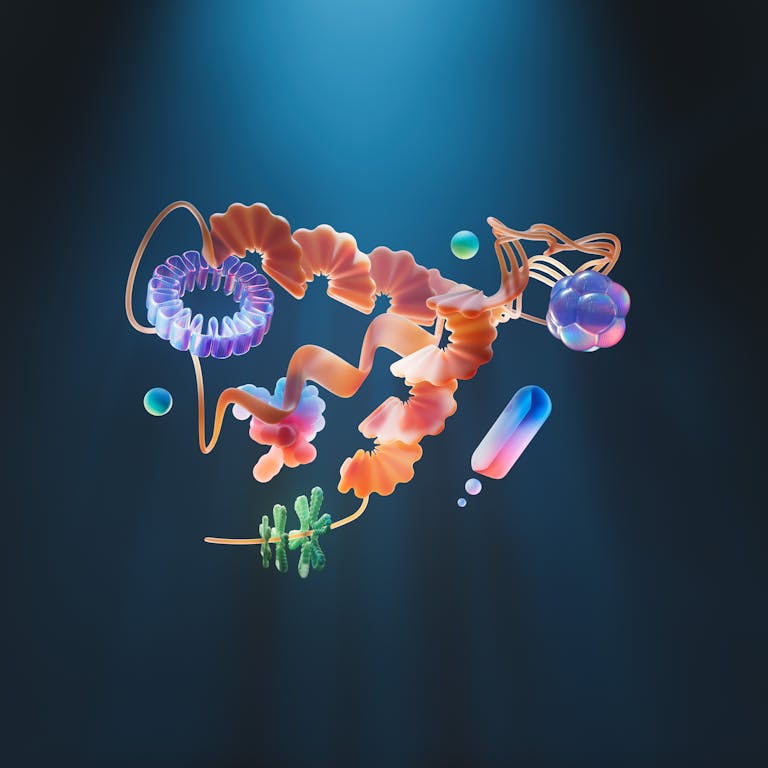

At the center of this discovery are structures called biomolecular condensates, including the well-known stress granules. These are dense clusters of RNA and proteins that form inside cells when conditions become unfavorable. For decades, researchers debated whether these granules were simply accidental clumps formed during cellular shutdown or whether they served a deeper biological purpose. The latest findings strongly support the second idea.

Stress Granules Are Not Accidental Clumps

When cells experience stress, they often slow down or stop the process of translation, where messenger RNA (mRNA) is used to make proteins. Traditionally, scientists assumed that stress granules formed as a side effect of this shutdown. The idea was simple: if translation stops, unused mRNAs and proteins pile up, and stress granules are just the result of this molecular traffic jam.

However, researchers led by biochemists studying budding yeast—a classic model organism—found strong evidence that this explanation is incomplete. Instead of random accumulation, cells actively gather and store mRNAs in condensates when stress begins. This allows them to preserve unfinished work and rapidly shift their focus to producing proteins that are immediately needed for survival.

In other words, stress granules function like a pause button, not a trash bin.

Timing Matters More Than RNA Type or Size

One of the most surprising discoveries from the study is that nearly all pre-existing mRNAs are pulled into condensates once stress hits. Earlier theories suggested that only long or “sticky” mRNAs were likely to clump together. But detailed biochemical analysis showed that mRNA length, sequence, and function did not matter.

The only factor that mattered was when the mRNA was made.

mRNAs that existed before stress began were almost universally sequestered into condensates. In contrast, mRNAs synthesized after the stress response started were largely excluded. This means the cell does not selectively choose which genes to pause based on content—it chooses based on timing.

This timing-based separation allows cells to temporarily shelve older instructions while continuing to translate new messages that are specifically relevant to handling the stressful condition.

How Cells Separate Old and New Messages

The researchers believe this separation happens because of changes at the ends of mRNA molecules, where translation normally begins. When translation stalls, the ends of older mRNAs become exposed and available to interact with other molecules. These exposed ends help pull the mRNAs into condensates.

Newly synthesized mRNAs, on the other hand, appear to have their ends protected in some way, possibly by associated proteins. This protection prevents them from being dragged into condensates, allowing them to remain active and continue producing proteins during stress.

Although the exact protective mechanism is still unknown, the results show that cells have a built-in system for prioritizing urgent genetic instructions over older, less immediately useful ones.

Condensates Exist Even Without Stress

Another key finding reshapes how scientists think about stress granules altogether. The researchers discovered that cells form many small, previously overlooked condensates even under normal conditions. These tiny structures appear whenever translation is temporarily paused, which happens frequently during routine cellular processes.

The team named these structures Translation Initiation Inhibited Condensates, or TIICs (pronounced “ticks”). Unlike classic stress granules, TIICs are often too small to see under a microscope. Yet biochemically, they behave in similar ways.

Importantly, TIICs form independently of stress. Even when scientists used drugs to block stress granule formation, TIICs still appeared. This shows that condensate formation is not exclusively a stress response but a general strategy cells use to manage mRNA and proteins.

Stress Granules Are the Visible Tip of the Iceberg

These findings suggest that what scientists traditionally call stress granules are just the largest and most visible version of a much broader phenomenon. Condensation of mRNA and proteins begins at a smaller scale with TIICs and only later develops into large granules when stress is severe or prolonged.

This means that cells are constantly reorganizing their internal components in time and space, even during normal growth. Stress simply makes these processes easier to observe.

Rather than being passive victims of harsh conditions, cells actively reshape themselves to maintain efficiency and flexibility.

Supporting Evidence From Independent Research

The conclusions are reinforced by a second, independent study conducted by researchers at ETH Zurich. That work showed the same timing-based pattern during stress caused by glucose deprivation. Once again, mRNAs produced before stress were stored in condensates, while those produced afterward remained available for translation.

Together, these studies demonstrate that timing of transcription is a fundamental principle governing how cells respond to sudden environmental changes.

Why This Changes How We Think About Cells

For years, stress granules were treated as odd side effects—useful markers of stress but not necessarily meaningful on their own. This new research reframes them as active regulatory tools.

Cells are not simply shutting down under pressure. They are reorganizing, prioritizing, and planning ahead. By storing older mRNAs and keeping new ones active, cells gain the ability to rapidly switch programs without losing previous work.

This perspective also fits with a growing appreciation of biomolecular condensates across biology. Similar structures are involved in gene regulation, signaling, and even development. Problems with condensate regulation have been linked to neurodegenerative diseases and other disorders, suggesting that understanding these processes could have far-reaching implications.

A Broader Lesson About Cellular Intelligence

One of the most important takeaways from this research is that cells behave in ways that appear deliberate rather than accidental. Molecular biology increasingly shows that many cellular structures once dismissed as byproducts are actually finely tuned systems shaped by evolution.

Condensates are not just emergency storage bins. They are part of a dynamic organizational strategy that helps cells survive uncertainty, conserve resources, and respond quickly when conditions change.

As research continues, scientists expect to uncover even more roles for these structures, not only in yeast but across all eukaryotic life.

Research Papers

Transcriptome-wide mRNP condensation precedes stress granule formation and excludes new mRNAs

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2025.11.003

Timing of transcription controls the selective translation of newly synthesized mRNAs during acute environmental stress

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2025.11.004