How Ecosystem Interactions Are Driving the Spread of Seagrass Wasting Disease in Eelgrass Meadows

Eelgrass meadows may look calm and unassuming from the surface, but beneath the water they form some of the most productive and important coastal ecosystems in the Northern Hemisphere. These dense underwater plants stabilize sediments, improve water quality, reduce shoreline erosion, buffer against sea-level rise, and provide essential habitat for fish, shellfish, and countless small marine organisms. Despite their importance, eelgrass ecosystems across the United States and around the world are increasingly under threat, and one of the most persistent challenges they face is seagrass wasting disease.

This disease, caused by a fungus-like protist called Labyrinthula zosterae, is now widespread across eelgrass meadows and is quietly reshaping coastal ecosystems. Researchers are uncovering how the disease spreads, why it becomes deadly in some cases, and how interactions within the ecosystem itself play a major role in determining its impact.

Understanding Seagrass Wasting Disease

Seagrass wasting disease manifests as distinct black lesions that form on eelgrass leaves. These lesions block photosynthesis, slow growth, and weaken the plant over time. In severe cases, they can lead to plant death and the collapse of entire meadows.

While the disease first gained attention during massive eelgrass die-offs in the 1930s, modern outbreaks are different. Today, most eelgrass meadows show signs of chronic, low-level infection rather than sudden, catastrophic loss. The challenge for scientists is that it is currently very difficult to predict whether a mild outbreak will remain manageable or eventually escalate into a devastating event.

The pathogen itself, Labyrinthula zosterae, spreads across eelgrass leaves using a mucus-like network, allowing it to move between cells and expand lesions over time. Genetic studies have shown that not all strains of the pathogen behave the same way, with some proving more aggressive and infectious than others.

Why the Disease Is So Hard to Detect and Predict

One of the most important discoveries in recent research is that wasting disease does not usually kill eelgrass outright. Instead, it places a heavy energetic burden on the plant.

Eelgrass stores sugars in its underground stems, a reserve often described by scientists as a battery. These energy stores help the plant survive harsh conditions such as winter darkness or temporary environmental stress. When the disease interferes with photosynthesis, that battery slowly drains.

Early data suggest that it may take multiple disease outbreaks over several years to fully deplete these energy reserves. Once that happens, eelgrass plants become far more vulnerable, and entire meadows can suddenly disappear. This delayed effect makes it difficult for managers to recognize danger until damage is already severe.

Environmental Stress Makes the Disease Worse

Wasting disease is especially dangerous when eelgrass is already struggling with other environmental pressures. Warming seawater has emerged as one of the most significant factors increasing disease severity. Higher temperatures can accelerate pathogen growth, weaken eelgrass defenses, and disrupt the balance of microbial communities living on eelgrass leaves.

In this way, wasting disease mirrors many other marine infectious diseases, which often remain manageable until environmental stress tips the balance. Heat waves, storms, and changing water chemistry can all compound the effects of infection, leaving eelgrass meadows less resilient to disturbance.

Despite these risks, wasting disease is not routinely monitored, meaning outbreaks can progress unnoticed until substantial ecological damage has occurred.

Long-Term Research Across the U.S. Coast

To better understand these dynamics, researchers from multiple institutions have been studying eelgrass meadows in Washington state since 2012. The team includes scientists from Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, the University of California Bodega Marine Lab, Old Dominion University, Cornell University, and the University of Washington.

This long-term dataset has allowed researchers to track disease prevalence, plant health, and environmental conditions over nearly a decade. Field experiments include mark-recapture studies, where individual eelgrass shoots are tagged and monitored every two weeks. This approach helps quantify how fast lesions grow, how infections spread, and how frequently infected plants die.

In parallel, scientists are sequencing different strains of Labyrinthula zosterae to understand why some infections progress rapidly while others remain mild.

The Role of the Broader Ecosystem

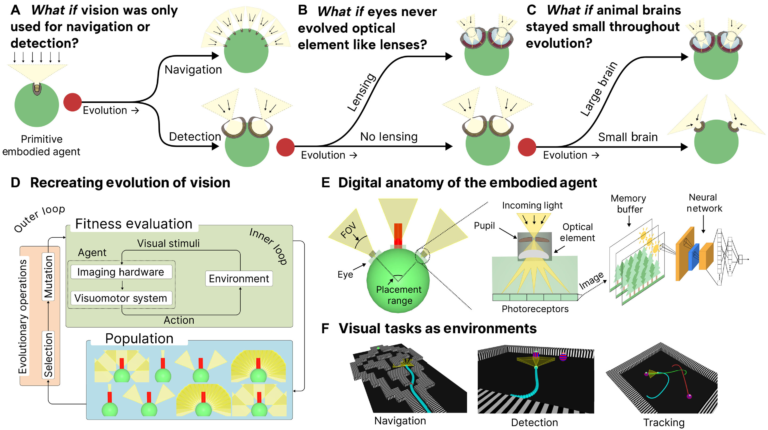

One of the most important insights from recent research is that wasting disease cannot be understood in isolation. Ecosystem interactions strongly influence disease spread.

For example, oysters appear to play a protective role by filtering the pathogen out of the water. In contrast, certain bacteria living on eelgrass leaves may actually facilitate infection. Grazing organisms can also worsen disease by creating wounds that give the pathogen easier access to plant tissue.

These findings highlight the importance of looking at the entire biological community, rather than focusing only on the pathogen and its host. Small changes in species composition can dramatically alter disease outcomes.

Modeling the Future of Eelgrass Meadows

Researchers are now working to turn these insights into predictive tools. Current models track how lesions expand across individual eelgrass leaves. The next goal is to scale these models up to include multiple leaves, entire plants, and eventually full meadows.

Such models could help scientists predict how wasting disease will respond to warming waters, identify conditions that increase mortality risk, and guide restoration efforts. Understanding these feedback loops is especially important as climate change accelerates and restoration projects become more widespread.

Education and the Next Generation of Marine Scientists

Beyond research, the project has placed a strong emphasis on education and training. Graduate-level summer workshops at Friday Harbor Laboratories use wasting disease as a model system for teaching marine disease ecology. The disease is relatively easy to observe in the field and grow in the lab, making it an ideal teaching tool.

The team has also invested in high school outreach programs, helping introduce younger students to marine science and ecosystem health.

Why This Research Matters Beyond Eelgrass

Seagrass wasting disease is not an isolated problem. It reflects broader trends affecting foundational marine species such as corals and kelps. As oceans warm and ecosystems face increasing stress, diseases that were once manageable can suddenly drive large-scale population declines.

By identifying the environmental and ecological “levers” that influence disease spread, scientists hope to develop strategies that support conservation, restoration, and long-term ecosystem resilience.

Research Reference

Aoki, L. R., et al. Wasting disease of a marine foundation species links community interactions to disease dynamics. Biology Letters (2025). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2025.0579