How Encapsulation Shapes the Evolution and Possibility of Living Cells

Encapsulation sits at the heart of how life organizes itself. A cell, at its core, is simply a container—a bounded space that holds the chemistry required for life to function. Although this idea sounds simple, a new study digs into how difficult it actually is for life to fit itself inside a container and what limits this process places on organisms on Earth, in lab-grown synthetic systems, and even on possible life beyond our planet. The research, conducted by SFI Professor Chris Kempes and colleagues, offers a detailed look at the constraints that shape living cells and the chemical systems within them.

What the Researchers Investigated

The team explored one central question: How hard is it to encapsulate life? To answer this, they turned to a mathematical model of a bacterial cell that they had developed in earlier work. This model allowed them to tweak how quickly internal components carried out their chemical roles.

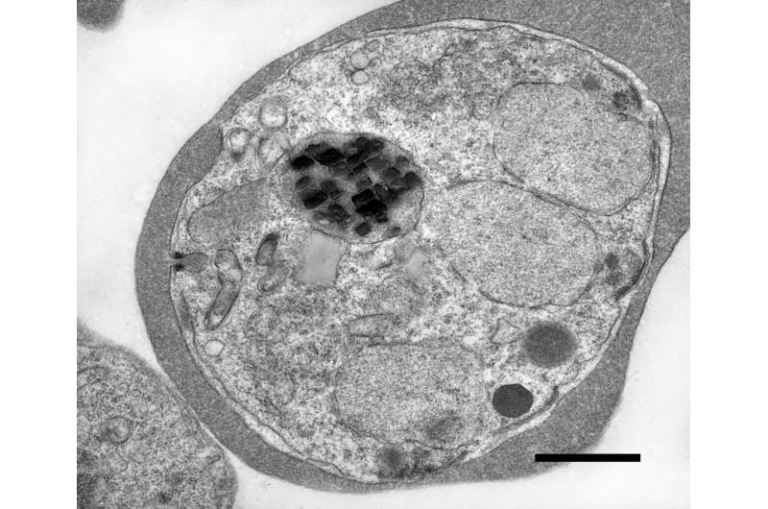

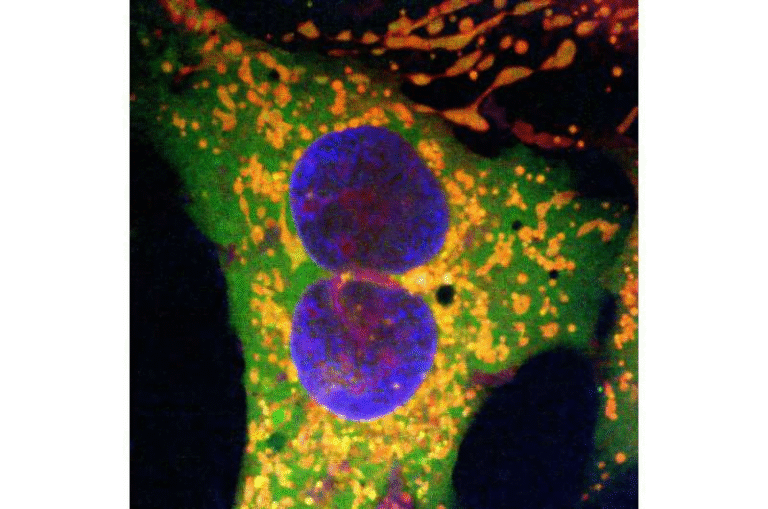

One clear example came from adjusting the rate at which ribosomes produce proteins. Ribosomes are major molecular machines inside cells, and they occupy a significant amount of cellular space. When the researchers slowed ribosomal activity in their model, something interesting happened: the cell needed more ribosomes to keep up with protein demands. As more ribosomes accumulated, they crowded the interior, leaving too little room for other essential components. This extreme crowding leads to what the researchers describe as a ribosome catastrophe, a situation in which the cell becomes nonviable simply because it cannot physically fit everything it needs inside its boundaries.

On the other hand, when ribosomes worked faster in the model, the cell could remain larger and avoid catastrophic overcrowding. Faster internal chemistry meant fewer ribosomes were required, freeing space and allowing a more complex internal structure. This demonstrated that reaction speed directly affects how much chemistry can fit inside a cell, forming one of the key principles behind encapsulation.

Developing a General Model for Encapsulation

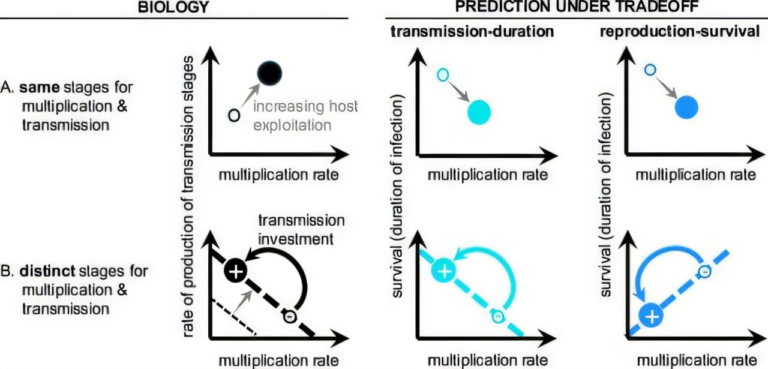

Using these insights, the authors created a generalized encapsulation model — a framework they could use not only for Earth-based organisms but also for entirely hypothetical forms of life, whether synthetic or extraterrestrial. They tested this model on two broad categories of living systems:

- Autocatalytic Systems

These are networks of molecules that replicate themselves without needing genetic information. Autocatalytic sets are often proposed as plausible early-life systems because they do not require distinct genetic and enzymatic machinery. - Genetic Systems

These systems contain molecules that store information—analogous to DNA or RNA—and others that carry out chemical functions. They are more elaborate than autocatalytic networks.

For both types, the new model revealed universal constraints. If chemical reactions inside a system take place too slowly, the system cannot fit within a container without overcrowding. Slow chemistry demands more catalytic machinery, which increases molecular mass and spatial requirements. If the internal parts grow faster than the container can hold, encapsulation becomes impossible. Conversely, faster chemistry enables larger and more complex systems that can counteract molecular loss due to decay or dilution in the environment.

Why Encapsulation Matters for the Evolution of Life

Compartmentalization is considered fundamental to the origin of life. Without a boundary—whether a membrane, a vesicle, or another physical enclosure—molecules drift apart and cannot cooperate long enough for evolution to take shape. By studying encapsulation, the researchers addressed a foundational question: What conditions allow a collection of molecules to function as a cohesive, evolving unit?

The study suggests that simply enclosing chemistry in a container is not enough. The balance between reaction speed, molecular abundance, and available space determines whether life can emerge and sustain itself. This means that certain forms of slow or inefficient biochemistry may be physically incapable of forming a viable cell, no matter how favorable the environment might seem.

Implications for Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology aims to create artificial life or life-like systems in laboratory settings. The new model highlights several practical limitations:

- Designing artificial cells requires matching internal reaction rates with feasible container sizes.

- Slower systems may need unrealistic amounts of catalytic machinery, making them impossible to contain.

- Faster synthetic chemistries offer more flexibility and stability.

The research essentially provides a rulebook for designing viable artificial cells, showing what combinations of size, chemistry, and reaction dynamics can realistically coexist.

Implications for the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

In astrobiology, scientists often speculate about what alien life might look like. Many models assume some kind of compartment—perhaps an icy shell, a lipid membrane, or a mineral boundary. This study provides constraints that apply universally, regardless of environment:

- Life anywhere must balance chemical rates with available container volume.

- Extremely slow chemistries may never achieve stable encapsulated structures.

- Environments that promote faster reaction kinetics could support more complex organisms.

This means that by studying the energetic and chemical conditions of planets and moons, we can better estimate whether encapsulated life is even possible there.

Additional Background: Why Cells Need Space

Inside even the simplest bacterial cell, thousands of molecular interactions occur every second. Ribosomes, enzymes, metabolites, and structural molecules all compete for space. If too many molecules are required to maintain basic functions, the cell becomes physically overloaded.

Scientists refer to this as the macromolecular crowding problem. The new study reframes this issue by connecting it to evolutionary constraints: if crowding grows too severe, the system collapses before evolution can refine it.

Additional Background: The Origin of Cellular Compartments

Various theories try to explain how the first compartments formed on early Earth:

- Lipid vesicles can self-assemble spontaneously, forming natural boundaries.

- Mineral pores in hydrothermal vents may have acted as primitive compartments.

- Coacervate droplets, formed by charged polymers, can also trap molecules and create internal microenvironments.

Each of these candidates must still meet the constraints identified in the new model: the chemistry inside must be fast enough and lean enough to fit within the compartment without overcrowding.

What Makes This Study Important

This research provides a quantitative way to evaluate whether a set of chemical reactions can be physically contained. It helps clarify:

- Why certain biochemical architectures are possible while others are not.

- How early life may have evolved toward faster and more efficient reactions.

- What limits extraterrestrial or synthetic organisms must obey.

By connecting cell size, internal chemistry, and evolutionary potential, the study ties together multiple disciplines—biology, physics, chemistry, and planetary science.

Conclusion

Encapsulation is more than just putting chemistry inside a bubble. It is a delicate balance between reaction speed, molecular volume, and environmental factors. This study sheds light on why life on Earth looks the way it does, why cells evolved toward particular biochemical strategies, and what might be required for life to exist anywhere else. It shows that the very architecture of life is dictated by these physical constraints, giving us a deeper appreciation for how living systems organize themselves and persist through time.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2024.0297